Appreciations

View(s):Those Pera days and golden memories of ‘Mac’

Ernest Thalayasingham Macintyre

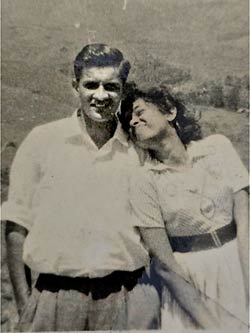

Ernest Macintyre and wife Nalini

I first met Mac and Nalini in my first term at university, when all three of us had small roles in the last play Professor Lyn Ludowyke produced for the Peradeniya University Dramatic Society.

At that time, they were simply two fellow undergraduates, showing no outward signs of the extraordinary partnership that would later define their lives. They did not adopt me as a couple — they adopted me as two individuals. I, in turn, was a painfully young-looking fresher who resembled a schoolboy who had wandered into adult company by mistake, and they took me under their wings with a generosity that never once felt patronising.

That production was Bernard Shaw’s ‘Androcles and the Lion’, and it set the tone for much that followed. The cast and crew numbered about twenty, and Professor Ludowyke hired a bus to take us across the island to Batticaloa on the east coast — famous for its singing fish and for Burghers who spoke, sang, and joked in a curious blend of three dialects. We staged two performances to packed houses, mostly schoolchildren, and on the Sunday morning we went to Kalkudah Beach, where you could walk for over a hundred yards and still not have the water reach your waist.

It was there that Mac’s wicked sense of humour first revealed itself to me. He persuaded me to strip and wade into the sea, fully aware that my adolescent modesty would suffer a blow from which it would take years to recover. I had to wait until the start of the next academic year before I could persuade a first-year female student to speak to me again.

These days, memory plays cruel tricks, but I remain convinced that Mac and I lived for a time in the Colombo south suburb of Wellawatte. During university vacations, we met regularly at Lion House, a modest coffee shop nearby. It was there that we discussed, with all the confidence of the very young, how Mac should propose to Nalini. The Junior Common Room at Sanghamitta Hall offered no secluded corners, and I suggested — cheekily — that he write her a letter instead.

I even proposed a sentence for inclusion, one so outrageous that I still blush to recall it. Whether wisely or diplomatically, Mac ignored my advice. What I do know is that Nalini replied, saying she had something important to tell him, and that she would like to walk with him to the riverbank. Anyone who knew Nalini will recognise how perfectly that moment captures her grace and quiet authority.

Mac’s work as a dramatist reflected the same moral seriousness and imaginative courage that characterised his life. His play ‘Irangani’, inspired by Sophocles’ ‘Antigone’, transplanted the ancient question of filial obligation into a Sri Lankan setting. It was not an academic exercise, but a deeply felt exploration of family, conscience, and moral duty — themes that mattered profoundly to him. Through ‘Irangani’, Mac showed how timeless human conflicts could speak with a local voice, without losing their universality.

He achieved something equally powerful in ‘The Government of Beddegama’, his stage adaptation of Leonard Woolf’s ‘Village in the Jungle’. I was fortunate to play a small role in that production, and it gave me a rare glimpse into how Mac’s mind worked. He treated Woolf’s text with respect, but never with reverence. His loyalty was always to the lives of ordinary Sri Lankans — to their endurance, their suffering, and their dignity in the face of authority. Drama, for Mac, was never merely performance; it was a moral enquiry conducted

with compassion.

Taken together, ‘Irangani’ and ‘The Government of Beddegama’reveal the essence of Mac’s artistic legacy. He had the rare ability to unite intellect with humanity, scholarship with compassion. Whether drawing on Greek tragedy or colonial fiction, he reshaped his sources so that they spoke directly to us — about family, obligation, power, and dignity. These were not abstract themes for Mac. They were the values by which he lived, and which he passed on, quietly and generously, to those fortunate enough to know him.

-Valentine Perera

| His voice will live on in theatre, literature, and in the countless minds he shaped | |

| It is deeply painful to come to terms with the passing of Ernest Thalayasingham Macintyre. The news has left a silence that feels both personal and profound. For me, this is not only the loss of an extraordinary playwright and thinker, but the loss of someone who shaped my intellectual journey at its very beginning. Ernest Macintyre wrote the Preface to my first book ‘Island to Island’ which emerged from my doctoral research on his works, titled “Diasporic Longing and Changing Contours of Resistance in the plays of Ernest Thalayasingham Macintyre.” That gesture was not merely academic generosity. It was an act of faith, encouragement, and quiet mentorship that I will always hold close. I knew him first through his work. Through his plays, his satire, his deep political consciousness, and his unwavering commitment to theatre as a living, breathing social force. He was a pioneer of Sri Lankan English theatre and an equally vital presence in Australian theatre, articulating the grief, longing, resistance, and resilience of diasporic life with rare clarity and compassion. In recent days, I have found myself returning again and again to the Preface he wrote for my thesis. Reading it now, I am reminded of his intellectual sharpness, his generosity of spirit, and his belief that literature and theatre must bear witness to histories of displacement and struggle. His words continue to guide me, even in his absence. Beyond the scholar and dramatist, Ernest Macintyre was, to me, a father figure. Someone I looked up to with deep respect, awe, and admiration. His presence offered reassurance. His encouragement gave courage. His legacy will remain a guiding light. My heartfelt condolences to his family, to his loved ones, and to all those whose lives he touched through his work and his kindness. May they find strength in the immense legacy he leaves behind. Ernest Macintyre’s voice will not fade. It will continue to live on in theatre, in literature, and in the countless minds he shaped across homelands and islands. With remembrance, -Dr Thamizhachi Thangapandian (Member of Parliament (Lok Sabha)- South Chennai)

|

He planted the seeds that grew into the tree of Independence

F.R. Senanayake: Death centenary- January 1, 2026

“Erected by a grateful public to commemorate an inspiring life distinguished by, noble ideals and great munificence, and single-hearted devotion to the service of the motherland.”

“Erected by a grateful public to commemorate an inspiring life distinguished by, noble ideals and great munificence, and single-hearted devotion to the service of the motherland.”

In the late 1960s, a weekly ritual marked my journey to the lecture halls of Alexander College: crossing Turret Road, walking the length of what would later be renamed in honour of a pioneer of Ceylon’s nationalist movement, and pausing, always pausing, before the majestic statue that stood sentinel at the road’s end. There, beneath that bronze gaze, I would read the epitaph etched, its words burning themselves into memory.

Frederick Richard Senanayake, was a unique patriot who never inflamed divisions of caste, creed, or community, but treated every citizen with equal regard. As an undergraduate at Downing College, Cambridge, the young Ceylonese enjoyed the rare privilege of intimate association with C. Atherton, son of L. Atherton, the Chief Justice of the United Kingdom. It was in London that F.R. boldly proposed the formation of the ‘Maha Jana Sabha-Ceylon’, a vision of political awakening for his homeland. At 21, he was called to the Bar, returning to Ceylon in 1904 with dreams of justice and reform.

Yet his legal career would prove startlingly brief. F.R. appeared in court on only two occasions, but what occasions they were. In his first case, he successfully defended a poor man against none other than Sir Solomon Dias Bandaranaike in a camel shooting incident. His second and final appearance came in a murder trial, where duty called him to serve as junior defence counsel on the very day his only sister married S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike’s uncle. Family and profession collided, but F.R. chose justice.

Graphite and plantation magnate G.C. Attygalle’s two elder daughters had already secured unions that would reshape the nation’s future: one wed John Kotelawala, father of the future Prime Minister Sir John Kotelawala; the other married T.G. Jayewardene, uncle of the future President J.R. Jayewardene—both marriages occurring at the turn of the century. These were not merely family connections; they were the first stitches in a tapestry of political power that would define generations.

Then tragedy struck with devastating force. Francis Attygalle, the family’s only male heir, was assassinated in1905. The state accused his own brother-in-law, Kotelawala, as the main conspirator. The elite families of Ceylon were torn apart.

In the aftermath, the Kotalawalas retained F.R. Senanayake as one of their defence lawyers, a natural choice given his legal brilliance. But F.R., a man guided by conscience rather than convenience, found himself unable to proceed. Standing before the shattered Attygalle family, he immediately returned his legal fees to the defence and declared he would assist the grieving family.

The Attygalle matriarch watched this unfold with astonishment and profound emotion. In FR, she recognised something increasingly rare. In an era when marriages cemented political alliances and family fortunes, she offered FR the hand of her third daughter, Ellen, celebrated throughout Kolamunne, in Madapatha as the most beautiful of the three sisters. It was an acknowledgment of character, an invitation into the inner sanctum of Ceylon’s emerging aristocracy.

With that union, the final piece of the puzzle fell into place. The Senanayakes joined the Kotalawalas, Jayewardenes, Bandaranaikes and Wijewardens in an intricate web of blood and matrimony. Five families, bound by love, tragedy, and ambition, would dominate Sri Lankan politics for the next seven decades. When tragedy struck F.R.’s sister-in-law Alice Kotelawala, leaving her destitute after her husband’s death, FR didn’t hesitate. He took responsibility for educating and caring for her sons John (Jnr) and Justin, an act of familial duty with national consequences. John Kotelawala would later become Ceylon’s third Prime Minister, another thread in the tapestry FR was weaving.

From this remarkable constellation would emerge prime ministers and presidents, revolutionaries and traditionalists. When FR stepped off the boat from Cambridge, bar certificate in hand, Ceylon’s legal establishment expected another success story. What they got instead was a revolutionary in a three-piece suit. The year was 1912, and rather than arguing cases in colonial courtrooms, FR declared war on the empire itself, through temperance.

The British had engineered a perfect system of social control. Auction off arrack licences to the highest bidder. Watch tax revenue pour into government coffers. Ignore the villages crumbling under the weight of state-sanctioned addiction. It was policy as violence, dressed up as commerce. Where temple bells once marked village rhythms, now tavern doors swung open at dawn. The colonial government didn’t just permit the destruction, it profited from it. FR and his brothers saw through the arithmetic. This wasn’t about public morals. This was about colonial domination through demographic decay. Their temperance rallies pulled thousands, particularly young educated Ceylonese who recognized cultural annihilation when they saw it.

By 1914, F.R. Senanayake had become President of the Buddhist Theosophical Society he had co-founded with Colonel H.S. Olcott two years earlier, religious revivalist and political insurgent in one. When communal riots erupted in 1915, Sinhalese mobs torched Muslim shops across Colombo. Rather than stand aside, FR moved toward the chaos, sheltering Muslim families at their Woodlands premises, while patrolling burning streets, pleading with rioters to disperse. Governor Sir Robert Chalmers saw sedition, not peacekeeping. His temperance movement became, in official eyes, a front for insurrection. Arrest warrants followed. Punjabi and Marati troops from Bombay detained Senanayakes without charges; execution loomed. Freedom came through interventions by Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan and E.W. Perera, but FR emerged transformed. Imperial power had shown its face. Social reform alone wouldn’t suffice, Ceylon needed strategic political warfare.

Despite his qualifications for the Legislative Council, FR chose a different path in 1912: the Colombo Municipal Council, where local government meant direct impact. His shrewdest move came twelve years later. The 1924 Negombo Legislative Council race should have been contested. Instead, FR engineered his younger brother D.S. Senanayake’s unopposed election—political chess disguised as family support. This wasn’t brotherhood; this was reading the future. FR had identified in DS the exact temperament Ceylon’s independence required: patience to endure colonial bureaucracy, cunning to dismantle it from within. By securing that uncontested seat, FR launched the trajectory ending at the Prime Minister’s residence. While DS climbed, FR worked the networks, the Lanka Mahajana Sabha, the YMBA. When Sir D.B. Jayatilleke needed land for the Colombo YMBA headquarters in Borella, FR’s checkbook opened.

F.R. Senanayake spent his fortune as deliberately as a general deploys troops. Buddhist schools, educational institutions, cultural associations, each donation was an investment in national consciousness, each contribution a brick in the foundation of independence. He chose this path consciously, turning away from the life of luxury his wealth could have provided. While others in his position accumulated estates and titles, F.R. accumulated something far more valuable: the gratitude and loyalty of a nation awakening to its identity.

On January 1, 1926, while on pilgrimage in India, FR’s life ended suddenly. He was only 44. Yet he had planted seeds in soil he had prepared himself, and those seeds would grow into the tree of independence under his brother’s careful tending. FR didn’t need to see the dawn he had made inevitable. He had already become what that statue opposite Town Hall would forever proclaim: not just a patriot, but the conscience of a nation learning to stand on its own.

K.K.S. PERERA

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.