Reclaiming Martin Wickramasinghe

Born 10 years before the 20th century, Martin Wickramasinghe was one of the leading purveyors of cultural modernity in Sri Lanka, South Asia and Asia. This week marks his 135th birth anniversary, the next year his 50th death anniversary.

To quote Nalaka Gunawardena, “Rarely has he been surpassed in this country, in his time or since.” It is something of a paradox, however, that while Wickramasinghe continues to be celebrated every year, there has yet to be a definitive study of his contributions. Bawa, Keyt, Wendt, Lester and Ivan Peries, and the 43 Group: these figures have been written on, from different perspectives. Wickramasinghe, however, remains woefully under-studied.

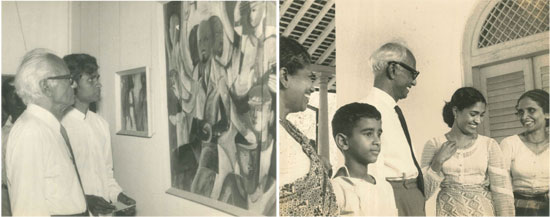

Lover of the arts: Martin Wickramasinghe viewing an exhibition and in-between the shoots in ‘Gamperaliya’. Pics courtesy the Martin Wickramasinghe Trust

At one level the problem is of language. In her brilliant book on Geoffrey Bawa, the historian Shanti Jayewardene places Wickramasinghe in the same league as Ananda Coomaraswamy, Lester James Peries, Cumaratunga Munidasa, and Anagarika Dharmapala. As she correctly implies, there were as many convergences between them as there were points of difference: Coomaraswamy’s conception of culture and modernity, for instance, could not have been more different to Dharmapala’s or Gunadasa Amarasekara’s.

The question as to where Wickramasinghe fits in this spectrum has never been asked, and it is one Jayewardene, rightly, does not answer. It is clear, however, that he fitted in no one’s mould, that he occupied his own intellectual terrain and, wisely, avoided the extreme positions that his contemporaries took. Yet from an early age, he formed his own ideas of culture and progress, of art and history, that remained with him throughout his life. These ideas were to give shape to his writings, as journalist, critic, and novelist.

The question as to where Wickramasinghe fits in this spectrum has never been asked, and it is one Jayewardene, rightly, does not answer. It is clear, however, that he fitted in no one’s mould, that he occupied his own intellectual terrain and, wisely, avoided the extreme positions that his contemporaries took. Yet from an early age, he formed his own ideas of culture and progress, of art and history, that remained with him throughout his life. These ideas were to give shape to his writings, as journalist, critic, and novelist.

In finding out where Wickramasinghe formed his opinions, we must invariably go back to original sources. Both Upan Da Sita and Ape Gama – the former more than the latter – are indispensable guides to his life and career. But in themselves, they are not adequate. His writings offer clues as well. As useful as the articles and books he wrote, however, are the articles and books he read. The Martin Wickramasinghe Collection at the National Library, which contains over 5,000 titles, is an indispensable guide.

Wickramasinghe was a voracious reader; he once called himself “omnivorous” in his reading habits. He read far and wide, indiscriminately but also critically. This is important, though it has not been appreciated. Interspersed throughout the pages of books at the National Library Collection are numerous marginal comments and annotations. They reveal the depth of his thinking, his ability to engage with what he was reading. Not surprisingly, many of the oldest books have marginal comments every few pages. This was only to be expected: he was reading these texts and learning about these subjects for the very first time. Lacking a formal education, he had no alternative but to read.

Unlike most other cultural modernists of his time, Wickramasinghe did not have to study or rediscover his culture. Keyt had to do so through literature and art, Wendt through photography, and Lester Peries through the cinema. As Tissa Abeysekera notes in a critique of the 43 Group, these artists fell back on a visual medium to compensate for their linguistic deficiencies. In this regard Wickramasinghe obtained the best of both worlds: he learnt Sinhalese and Buddhist texts at a young age, and he picked up a fluency in English which opened him to Western literature and scholarship later. In this as in much else, he remains highly unique and virtually unmatched.

Perhaps one reason Wickramasinghe has not been appreciated is that very few attempts have been made, in English, to study his writings in Sinhala. The 43 Group, and other cultural figures like Bawa and Wendt, offer almost no difficulty in this regard because, apart from communicating almost exclusively in English, they all worked in a visual medium. To read Wickramasinghe, however, it is necessary to immerse oneself in the culture and literature which he was born to, and which became his inheritance. As he recounts beautifully in Upan Da Sita, though lacking formal education he studied and learnt to critically examine such texts as the Saddharmalankaraya and Buduguna Alankaraya, preferring early on the writings of Gurulugomi to the Sanskritised ornateness of later scribes and poets.

Yet another reason has been the tendency to essentialise Wickramasinghe and to claim and appropriate him. As members of his family have themselves noted, the transformation of Wickramasinghe into a nationalist figure came long after his death. A perusal of his writings right before his death, however, paint a different picture of the man and his mind. Unlike a great many nationalists, if not chauvinists, for instance, Wickramasinghe held sympathetic views on the National Question and ethnic conflict. To his last, he remained supportive of S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike’s proposals for devolution of power and castigated the sections of the clergy who opposed his pact with S. J. V. Chelvanayakam.

His views on nationalism are best encapsulated in a series of articles that he wrote in the late 1960s and 1970s. It is easy to forget these interventions because, throughout much of his life, Wickramasinghe relentlessly criticised the Western-educated elite. But that he criticised the Anglicised elite did not mean he absolved those who committed the opposite error of being unremittingly uncritical of tradition and culture. For Wickramasinghe, one’s culture offered clues to one’s way of thinking and seeing the world. Yet as that world evolved, so did that culture. “The word nationalism,” he noted in his last significant such engagement, at the Prize Giving at Trinity College in 1971, “apart from the consciousness of the cultural unity of a community, means chauvinism.”

To study Martin Wickramasinghe, it is thus necessary to reclaim him from those who have appropriated him. This is not as difficult as one may think. A self-taught man, lacking formal credentials but eager to read and learn, Wickramasinghe made two contributions: transmit Western thought, science and culture to a vernacular audience, and write in English and for foreign audiences the tenets of Sinhala and Buddhist culture, as he saw and experienced it. Once we consider these twin achievements, rather unprecedented in their time, it becomes easier for us to appreciate the worth of the man.

(Uditha Devapriya is the author of four books, and is currently working on a study of Wickramasinghe, an official publication by the Martin Wickramasinghe Trust)

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.