Brilliant strokes of a great artist and milieu in which he moved

View(s):

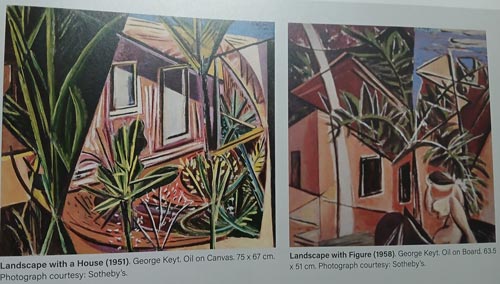

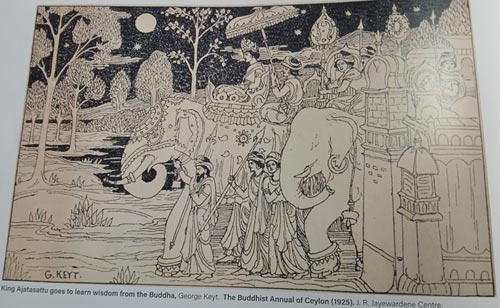

Illustrations from the book

There has been much written about George Keyt, but it was not till I had read this beautifully produced volume that I registered that a comprehensive account of the man and his work was long overdue. There had been three major studies produced before Keyt died in 1993, the first by his friend Martin Russel in 1950. The other two came out 40 years later, the first by another close friend, Ian Goonetilleke.

There have been two more recent books, one by an Indian scholar who used Russel’s archives to study Indian influences on Keyt, in a book aptly named Buddha to Krishna: Life and Times of George Keyt, the other by Albert Dharmasiri, perhaps our foremost expert now on Sri Lankan art. But Tammita-Delgoda goes further than all these in charting Keyt’s development from childhood, with due attention to his schooldays at Trinity College, and his eminently suitable marriage. But then he broke with convention, under the influence of his study of Buddhism, which was facilitated by access to the Malwatte Temple.

This led to what is one of the wonders of this book, a detailed account of the illustrations he did for various Buddhist publications that newspaper groups began to bring out in the 1920s, as an essential component of emerging nationalism. Though the book does not expand on this, the seminal work in this respect of Lake House under D.R. Wijewardene, also inspired the Times, while Buddhist Annuals were another regular outlet for a creativity based on a national vision.

But this new style was also influenced by movements in European art, and there are clear parallels with Picasso and cubism, Derain and fauvism, and other aspects of modernism that had broken with tradition. The book is brilliant in contrasting the work of Keyt and the other young artists who set up the 43 Group with that of the Ceylon Arts Society, which refused to display their work.

But this new style was also influenced by movements in European art, and there are clear parallels with Picasso and cubism, Derain and fauvism, and other aspects of modernism that had broken with tradition. The book is brilliant in contrasting the work of Keyt and the other young artists who set up the 43 Group with that of the Ceylon Arts Society, which refused to display their work.

Tammita Delgoda presents this through the lens of the mainspring of the group, Lionel Wendt, whose seminal influence is succinctly described, through his access to new work in the west and his deep commitment to this country. The account of Wendt, to anticipate, is a precursor to accounts of two other vital influences in Keyt’s life, the Indian writer Mulk Raj Anand who brought him into an artistic milieu in Bombay where his talent developed and flourished, and Ian Goonetilleke, Librarian of the University of Peradeniya, who was the still centre of Keyt’s increasingly turbulent world as he moved into old age with an energy that refused to diminish.

The writer is bold and clear in emphasizing how this energy, which expressed itself in art, was also evinced in rampant sexuality. That indeed contributed to the first major change in Keyt’s life and outlook, for he contracted a fervent passion for the nursemaid of the children of his first wife, and left her to live in a village with his Pilawela Menike as he renamed the erstwhile Lucia. Her devotion to him survived his many sexual liaisons with other women, his protracted absences in India – which involved many of these – and even the advent of Kusum, an Indian woman 30 years his junior who abandoned her husband to come to Kandy.

That however, caused ructions since Kusum imposed on Menika and soon enough she and Keyt had to leave, to live in various places including in Colombo for 20 years. Finally they went back to Menike in 1992, a year before Keyt died, and she took them in.

These last years involved much work not always of the previous high standard, for Keyt was short of money and Kusum’s insecurity meant he had to keep painting and drawing. Tammita-Delgoda does not fight shy of describing this period, nor indeed Keyt’s tendency to prey even on the wives of his friends, but since this is all piled up as it were in the last few pages it does not take away from the impression of his genius and its development over the first 70 years of his life.

The book is full of illustrations that show the changes Keyt could ring on even the most overworked of his subject matter. The female form was his principal interest, but the voluptuousness he celebrated is reshaped again and again, entwined with economically sketched desirable males to begin with and then, as he himself grew old, with angular bearded figures embodying the sages who relished sex, Keyt presumably numbering himself amongst them.

As I have noted, as interesting were the illustrations he produced for stories, for the annuals and for little tales and poems he wrote. The book avoids the Gothami Vihara murals, his most famous religious work, but there are plenty of similar subjects, while there are a few vignettes of Kandyan dancers and musicians and a couple of luscious landscapes.

The book also includes carefully chosen works by other members of the 43 Group, giving due weight in brief narratives to the most interesting of them, Harry Pieris, Ivan Peries, Justin Daraniyagala and of course Lionel Wendt. There are some splendid photographs by Wendt, and if there is one crime for which Keyt should not be forgiven, it is not his sexual promiscuity at the expense of friends but rather that he destroyed an archive of Wendt pictures after his friend’s death. Though a free spirit himself, perhaps his lack of interest in male beauty meant that Keyt thought of Wendt’s pictures as demeaning and could not understand their artistic excellence.

The book gives due weight to Keyt’s long suffering brother-in-law Harold Peiris, who apart from bankrolling Keyt at difficult times was responsible for setting up the Lionel Wendt Arts Centre. And there are brief but fascinating accounts of the cognoscenti who made Bombay a centre of the arts in the period around Indian independence. Thankfully, the book also highlights Mulk Raj Anand’s Story of India which Keyt illustrated with stunning line drawings.

The book is clearly a labour of love, given the efforts made to provide it with suitable illustrations, including lovely old pictures of Ceylon and India. There are splendid reproductions of modernist paintings, juxtaposed with those of the 43 Group to suggest the influences whilst also making clear the indigenous inspiration of the latter.

Apart from the work the writer has put in, there has also been massive input from his principal research assistant Uditha Devapriya, who is one of the brightest young journalists now on the arts scene. He has conducted interviews and collated material and prepared a bibiliography and other appendices with a dedication worthy of his subject. As a result the volume illustrates not just a great artist but the fascinating milieu in which he functioned, and a memorable period.

| Book Facts | |

| George Keyt: The Absence of a Desired Image by SinhaRaja Tammita-Delgoda Reviewed by Prof. Rajiva Wijesinha

|

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.