Savouring tales of Sri Lanka through her food

Celebrating family, food and her heritage: Cynthia Shanmugalingam. Pic by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

Cynthia Shanmugalingam realized the massive role food played in her life and in her family’s trajectory in and out of Sri Lanka when she came to Sri Lanka on a visit just after her grandmother died. They would go to the fish market every day to choose the freshest of fish and cooked vegetables plucked from the garden. As she watched her mother cook and navigate an open fire kitchen with dexterity, Cynthia realized that this style of cooking was not represented in London, where she lived, and she began feeling that she had a unique take on Sri Lankan cuisine that she wanted to share. She had just begun a restaurant incubator to help people start restaurants – this proved to be a great environment to be immersed in to learn about the restaurant industry – and this feeling began to ferment, gaining potency.

She began plans to open a

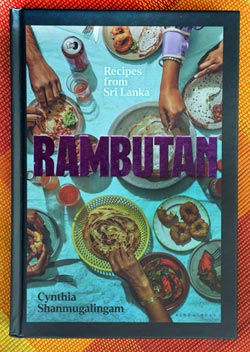

Sri Lankan restaurant in London when COVID descended. Like many industries heaving under the toll of the coronavirus, the hospitality business was in disarray. It was a terrible time to open a restaurant. A friend suggested that she distill her learnings for the restaurant into a cookbook and so the idea for Cynthia Shanmugalingam’s cookbook Rambutan was born.

“I felt like, especially because of my immigrant perspective, and because I’m Tamil, there was this insider-outsider story that I wanted to tell about the island and about our cuisine, and I didn’t want to shy away from the history of the island. And so, it’s a book about family and about family recipes and it’s a book about my perspective of coming here on holiday and having family come to live with us and being caught between two worlds, I guess,” says Cynthia, newly married and in Sri Lanka for the Galle Lit Fest and its partner festival Gourmet Galle, reflecting on the origins of the cookbook.

Rambutan, published in 2022, was received with praise and acclaim. It was winner of the Fortnum & Mason Best Debut Cookbook Award 2023 and lauded as one of the best cookbooks of 2022 by Delicious Magazine, Bon Appetit, the New York Times and LA Times.

Cynthia Shanmugalingam’s cookbook Rambutan is a love letter to Sri Lankan food and its rich culinary history. Packed with over 80 recipes, the cookbook combines memoir, socio-political history, personal photographs and vivid pictures of Sri Lanka to tell multiple stories through food. Rambutan, in many ways, feels like having a deeply irreverent, chatty friend guide you through the ins and outs of Sri Lankan food, demystifying it and experimenting with substitutions and adaptations.

The book uses nine essays as literary springboards to dive into various recipes. Cynthia’s family looms large in the book, and we see how her personal history is intertwined closely with food. “It was a beautiful experience for me to think of all the memories I had and there’s no memory I have of the island that isn’t touched by family. I wanted to evoke some of those powerful feelings,” she says.

We hear of her mother, who at 40 years of age, began English classes on Thursdays and Fridays in the UK, went on to complete her GCSEs, A Levels and trained as a teaching assistant while working a full-time job in a factory, cooking for a family of eight and looking after five children – two of whom weren’t her own. She writes of her father, who worked as a child labourer until he was fourteen, was the only student from his batch at Nelliady Central who got into the University of Peradeniya, moved to London in 1968 and the racism he faced while navigating work and life in a new country.

One of the most poignant moments in the book, is when Cynthia writes about her father’s little brother and the layers of displacement that occur for diaspora contending with notions of homeland and the loss of familial bonds. Her uncle was the one to introduce jakfruit, rambutan and mangosteen into her taste lexicon, and she writes of the emotional and physical whiplash they felt when he passed away as he was one of the strongest links they had to Sri Lanka.

Perhaps what also marks Rambutan is Cynthia’s homage to beloved Sri Lankan staples, and bold playfulness with technique and ingredients. Rambutan is a reminder that recipes are never static, that there are many paths to a Sri Lankan dish and you’re always welcome to forge your own.

In Rambutan, Cynthia roasts beetroot and pumpkin before currying them to coax the natural sweetness out of the vegetables. She terms her lamprais ‘lamprai-sh’ and takes care to note that her version pays homage to a lamprais and is not meant to be a lamprais (or as she refers to it in the book: “the good-looking Sri Lankan cousin of the famous Malaysian breakfast dish, nasi lemak”). In Cynthia’s version of lamprais, fried meatballs are substituted for frikkadels and panko-crusted soft-boiled eggs, yellow rice, a slow-cooked short-rib beef curry and a radish and cardamom yoghurt make up the lamprais. For puttu, she offers up instant couscous as a substitute for rice flour and coconut. Cynthia’s version of watalappan is a watalappan tart that is baked instead of steamed. In her maalu paan recipe, she incorporates the Japanese Tangzhong technique to yield fluffy, pillowy buns which last longer.

She also alludes to the social histories of many dishes and cultural cross-pollination that occurs in Sri Lankan cuisine. Love cake for instance, she notes, may have Arabic rather than European roots given its use of rose water and similarity to basbousa and similar sweets in the Middle East.

Another vital feature is the cookbook’s dealing of uncomfortable histories that make up the island’s narrative and even familial narratives.

“I think it’s a very important part of understanding the cuisine and understanding the meaning of it. I never want to do, in any of my work, a whitewashed idea of Sri Lanka. Like every country, it has its tragedies and its losses and that is part of it. And I feel like people want to know that. If you look at Anthony Bourdain’s work and other cooks, you know food is a way to discover new places and not just discover it on a surface level. For instance, we celebrate Sri Lankan tea, but it’s not enjoyed by the people who pluck it with incredible skill and who have done so for centuries. I wanted to make sure we were telling and understanding stories from – as many as I knew – the whole history of the island and from different communities,” reflects Cynthia.

In a chapter on Sri Lankan Muslim street food, the cookbook reflects on the Kattankudy Mosque Massacre and the killing of around 150 Muslim men and boys by the LTTE. In a chapter about short eats, she writes about the killing of her mother’s deaf cousin by the

Sri Lankan army for breaching curfew while taking some food for his aged parents, and the torture and detainment of a 13-year-old cousin who was left with debilitating PTSD he never recovered from.

“I do feel conscious that there is a younger generation of diaspora

Sri Lankans who grow up outside the island – and even those who grow up inside the island – who don’t know some of our history. It’s not taught well – I would say neither here nor abroad. And in any small way I always try and do that in anything that I write about – to try and create a three-dimensional story and experience,” says Cynthia.

If writing a cookbook is a solitary activity, running a restaurant is the opposite of it and is a gruelling exercise in collaboration. Cynthia’s restaurant Rambutan opened its doors in London in March 2023, hot on the heels of the success of her cookbook and marks its first year this year. The restaurant, which is in London’s Borough Market, much like its namesake cookbook, showcases Sri Lankan food with an emphasis on Cynthia’s Tamil heritage.

With a book and a restaurant out in the world in quick succession, the recent years have been hectic (“I haven’t slept that much over the past two years,” she laughs ruefully) but Cynthia is just getting started.

“Well, I’ve been thinking about doing something here [in Sri Lanka] actually. […] I feel like what Rambutan is doing is a little bit different and it could work well here. I would love to do maybe something on the beach that celebrated the cuisine and also Tamil cuisine with the diaspora touch. And again, cooking over a fire – that I think we do well in London. And then, we will do another one in London. I don’t know if it will be another Rambutan – that’s to be decided – but it will definitely be Sri Lankan cooking. I think there’s so much more to explore and to specialize in and different aspects of the cuisine to celebrate,” says Cynthia.

| A recipe from Rambutan: Jaffna Crab Curry | |

Serves 4

Heat the oil in a large saucepan over a medium heat. Fry the onions for 3 – 4 minutes, until soft. Add the garlic and ginger, and after about 1 minute when the garlic is starting to get fragrant, add the curry leaves, and cook for 30 seconds – 1 minute, so the curry leaves are bright green. Add the salt, SL curry powder and the crab. Sauté for 3-4 minutes to give the crab a nice colour and fragrance. Pour over just enough water so the crab is about half-submerged in liquid. Bring to a boil, then immediately turn the heat to a simmer and cook for 15-20 minutes. When it’s ready, the crab should be pink and if you prise any flesh, it should not be slimy or raw. Gently stir in the rocket leaves or mustard greens, if using, and coconut milk and cook through for 3-5 minutes. Switch off the heat and stir through a generous teaspoon of meat powder. Dish up immediately onto a big sharing platter. Seconds before eating, finish with a squeeze of lime. |

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.

If you get a live crab, put it in the freezer for 1 hour until it stops moving completely. Then, with your fingers lift and twist off the triangular flap under the crab and throw it away. With your fingers, lift and remove the head of the crab, which you should keep for presentation. Discard any grey juice but keep the yellow liquid as it is full of flavour. Cut the crab in half like you are slicing through the spine of an open book (and if it’s a big crab, into quarters too). Then pull off the claws and the legs. Crack the claws by tapping them with the back of a big knife to let the curry seep into the crab while cooking. Wash the crab pieces and set aside.

If you get a live crab, put it in the freezer for 1 hour until it stops moving completely. Then, with your fingers lift and twist off the triangular flap under the crab and throw it away. With your fingers, lift and remove the head of the crab, which you should keep for presentation. Discard any grey juice but keep the yellow liquid as it is full of flavour. Cut the crab in half like you are slicing through the spine of an open book (and if it’s a big crab, into quarters too). Then pull off the claws and the legs. Crack the claws by tapping them with the back of a big knife to let the curry seep into the crab while cooking. Wash the crab pieces and set aside.