Poems that open endless doors

‘Goodbye,

‘Goodbye,

we are not the first children

of bitterness.

Let lotus bloom in the ponds.

I will go

a little further,

blowing away everything.’

Lines from ‘A Journey’ (1998)

I first met Packiyanathan Ahilan some years ago, as an Art Historian and one of the extraordinary teachers in the Department of Fine Arts at the University of Jaffna. I knew, or was told, he was also a poet. But with my own failing of being bilingual on a trilingual island, I was not able to read his work, then only minimally translated. I was told to wait, a collection was being translated into English – published at last in 2018, by Mawenzi House.

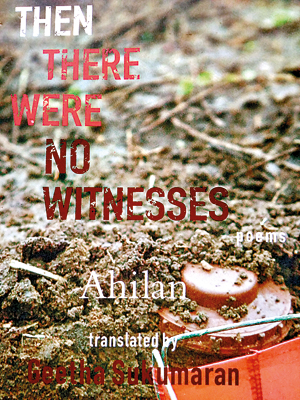

In this new collection, Then There Were No Witnesses, Ahilan’s poems are published as written, in Tamil, with an English translation by Geetha Sukumaran on every facing page. The way the poems are laid out in the book, even visually, the two languages look across at each other—each with its own history, literature, idiom and typography. Every question in the poems is thereby asked in two languages― in both unanswerable. Every physical absence or unspoken truth is doubly felt―freighted silences in this poetic conversation.The repetition of the poems reads as reiteration as well as ceaseless searching.

‘Tell me,

how can I protect

the candle flame of love

in this howling wind?’

Lines from ‘The Cross’ (1991)

To write about the book then as I do,― able to read the poems in English but not in Tamil, and lacking a deeper consciousness of their place in Tamil literary tradition and history ―is only to write partially, like a head disconnected from the heart. The reason I do so at all,is because that inadequacy is another culpable silence in our collective history.

The war is a weight throughout the collection, but we know it through portraits of life lived, parted and lost in its storm.

‘You shared the last drop of tea.

All the evenings

with their brocaded edges

are trammelled up.’

Lines from ‘A Journey’ (2005)

The poet is almost the soul of loss itself, speaking from within people and places left behind and also from within the people leaving. In ‘Narratives’, the speaker is ‘an unwanted/unclean visitor,/filling your verandas,/an illegal immigrant/crossing borders covertly’ but he tells us ‘You do not know—/My house in the/ancestral roots of history/was stolen and/ my streets hanged’.

One of the most powerful aspects of the collection is precisely the way that Ahilan layers his portraits; the war is a permanent shadow, even when it is not in the foreground of a poem (whereas sometimes it is). In ‘Untitled Love Story 04’ young lovers meet in middle age (‘You glance at my wife/ from the corner of your eyes,/I glance at your husband/ while you look away’). In what could be a story of young love grown old in any time or place, there are still the echoes of forced leaving:

‘Eyes meet and take leave;

a faint perfume of rose

spreads in the air.

I lose my poise

in a moment

like an adolescent’

Lines from ‘Untitled Love Story 04’ (2011).

Elsewhere, ‘a stranger exits/ opening endless doors’ (‘Mithunam 02’). There is a delicacy in Ahilan’s writing that is like a laying of flowers in language, itself a tribute to the fineness of feeling. The poems― as I read them in Geetha Sukumaran’s elegant translation― are spare, each excerpted phrase a world in itself, the lines near translucent in their clarity.

‘I am building a memorial,

not with stone,

not with water,

but with air,

the sound

that trails me forever’

Lines from ‘Semmani 03’

(2009-10)

What happens then when the most explicit terrors come? Then, the poet faces, unflinching, the dismembered horrors of war. A section of the book is dedicated to the aftermath of the final battles of 2009, with a number of poems spoken in the voice of morticians. Take the extraordinary ‘Leg’: it begins ‘They brought a leg in today’ and ends by asking

‘Isn’t it astonishing?

The leg had a head,

And the head had two eyes’

Lines from ‘Leg’ (2011)

These violated bodies test and prove Ahilan’s poetics – at this point in the collection the reader is grateful for a voice that allows a detail to attest the whole, never attempting the impossibility of a full outline. It is precisely because Ahilan’s poetry is spare that it can approach horrors of this scale.In her finely-tuned introduction to the collection,Geetha Sukumaran describes it as ‘a cubist style of poetry’, an approach she likens to Picasso’s Guernica. In these poems, the poet edges into a wry, absurd voice – none other perhaps is possible.

The poems’ translator also makes the striking point that in Ahilan’s poetry the ocean does not play a central role, the location is rather the street:

‘I gazed strangely at the wind

that lost its path

in the long

narrow pathways,

between the dark corners

of buildings’

Lines from ‘The Summer Rain’ (2015)

The poems inhabit a quotidian landscape, our everyday places. And in that landscape is also rain, as humdrum as it is mythical.

‘No goodbye: there was no time.

You left—

storm.’

Lines from ‘2005’ (2006)

It rains throughout Ahilan’s poems, in different sorts of downpour. The rain is persistent, like the comings and goings of wartime, and Ahilan’s poems take shape in a season of rain – as ever interchangeably grief, violence and water.

‘“Turning into pouring rain

I will remain damp”’

Lines from ‘Rain’ (2016)

Translator and poet: Geetha Sukumaran and P. Ahilan

A feeling of suspension runs right through the collection, the uncertainty is permanent because it is unresolved.The poems themselves span a period from 1990-2017 (27 years, familiar length of time). Time does not soothe; it keeps awake the agony.Only the precise calibration of precariousness changes over time and the events of war, underlining the dignity of persisting through all of it:

‘When bombers pause awhile,

the life in our hands

shudders further’

Lines from ‘Days of the Bunker I’ (1990)

‘Seventeen years have gone by—

awaiting eyes closed forever,

I cannot ask anyone

to light a lamp for the

father salted away.’

Lines from ‘Semmani 02’ (2010)

‘We are here now.

Eating without hands,

seeing without eyes,

walking on wooden stumps.

We are here,

Beneath your shining silk banners

It is us.’

Lines from ‘The Defeated II’ (2013)

This is poetry that itself opens ‘endless doors’, as the best poetry does. It is a collection I feel sure I will read and re-read, each time getting caught on a line or feeling I had not noticed before. It is poetry that insists on existing, and invokes what we cannot fully express:

‘Further down,

an expanse of silence,

untouched by the roots

of trees.’

‘Introducing Layers of Earth’ (2010).

| Book facts | |

| Then There Were No Witnesses Poems by Ahilan, translated by Geetha Sukumaran |