Drawn to the author’s journey of self-discovery

View(s): For a reader aware that the author of this autobiography was a onetime-JVPer, the title, Rebel Meets Liberation, would seem intriguing. Here, then, is someone who professes to have found salvation at the other end of their socialist dream?

For a reader aware that the author of this autobiography was a onetime-JVPer, the title, Rebel Meets Liberation, would seem intriguing. Here, then, is someone who professes to have found salvation at the other end of their socialist dream?But no, the 570 something pages of this memoir do not wax lyrical on the key to ‘heaven on earth’ being that proffered by Marx or Lenin. In fact the rebel, the autobiographer, would meet liberation by eschewing all kinds of politics, and his path there had nothing to do with his escapades in the 1971 insurrection. The JVP episode actually served him as rigorous asceticism served the Buddha- by convincing him early that it was not the true path.

The first part of the story is that of a village boy, growing up deeply sensitive to the inequity of the class system and the distribution of wealth in a Kandyan village. In his adolescence when the moon landing happened in 1969, Jayatissa, like so many other youths, was growing increasingly disenchanted with the entrenched worldview of the traditional villager (to whom the moon was a deity).

The rather homespun English of the book often seems to want elegance, but this is made up for by the frank honesty the author never fails to stand by. He describes the poverty at home and ill treatment by teachers at school, but the most impressive is the way he lays bare his soul. This endearing frankness, and the access to his inner self, is what makes the book such a compelling read, because the book charts his spiritual evolution from toddlerhood to sixties: the extraordinary saga of an ordinary man.

The streak that led him to dream of a new heaven and new earth the communist way, manifested itself early at school in what the author calls “Robin Hood activities”. He came to believe that “it was fair and rational to get involved in thefts and robberies, not for one’s own sake, but for the sake of the helpless poor.” They would steal pens off the better-to-do students as well as library books, and pass them over to poor students.

It was natural, therefore, for him to warm towards the new ‘liberation movement’, giving up movies and idle roving with friends. Kumarage chronicles how the collective imagination of his generation was inflamed by the magic of Communism, the charismatic visions conjured up by JVP party leaders. You feel the intoxicating headiness of their dreams, however misplaced and misled.

He was hardly eighteen when, during the first JVP insurrection in 1971, he led the attack on the Kadugannawa Police station. His account, capturing in palpitating immediacy that ultimately doomed operation, also shows just how hasty, poorly coordinated and even naive the whole insurrection was.

His picture of life in prison, after handing himself over, is not at all a completely negative one. True, he got beaten up and has some stories of injustice and horror, but the picture seeps in also of a place of sanctuary, rather like an austere monastery (with perhaps a stronger sense of fraternity among the inmates).

It was at Bogambara Prison that Jayatissa opened up to the pleasures of reading, and also learnt English- which made him ponder on his experiences and which would spur him on his path towards ‘liberation’. Authors from Rabindranath Tagore to Dostoevsky and Edgar Allan Poe would be luminaries for him. It is also telling of the prison’s role as an intellectual asylum that fellow inmates Victor Ivan, Ananda Perera and Sunanda Deshapriya would write or translate communist works into the night, using the single naked bulb that was allowed on till midnight.

The jailbird who returns to his hometown, Pilimatalawwe, after eight years, is a grown man. Thankfully his experiences, instead of making him cynical, have liberated him. Disillusionment with the JVP had set in as soon as the initial attack failed, and the irresponsibility of party leaders disgusts him. The book is a harsh critique of left wing politics. Kumarage was to learn through a baptism of fire that the visions of glory conjured up by the charismatic leaders would evaporate as soon as they made contact with reality.

“The (leaders) knew so much about Soviet society, Cuban society and Chinese society, but nothing about the country where they lived. They could win the awe of their followers with their inflated political language, even though some followers had no idea what they meant… I could see that other parties were actually many times closer to the people than they were.”

The power-hunger of politicians comes in for a severe lashing in the book as the cause triggering youth unrest.

The narrative also asserts the importance of English in helping shatter those fetters that keep us small minded, our vision narrow and dim. If the book has its moments of terror, it is also leavened by real-life humour, for instance Jayatissa getting drunk and sleeping on the chief monk’s bed while making liberal use of the spittoon.

The second half of the book, following prison, is saturated with wisdom born of experience. You feel the writer enjoy inhaling the heady spring smell of thinking free, having broken off from the shackles of conventional thought.

It is a book that is rewarding despite its lack of polish. You will be with him on a journey of self-discovery and illumination, and whoever you are, the book has something to make you ponder deeply. Sometimes the narrative seems to slip towards mundanity but each small graze of heart, each slight, becomes a life lesson. Having been privy to his spiritual growth from childhood, we see how his independent mind was moulded. He was a sensitive, reflective, taciturn and observant child with a strong moral sense. When someone like that is thrown into the heart of the social melee and experiences society in its full gamut, the result- as Kumarage manifests- can be prodigious.

It is an unusual autobiography in that it inculcates much free thinking. Recording classroom discussions with his students or through personal ponderings and reflections, the writer imparts his thoughts to the reader. He also analyzes festering social ills, running to earth their causes with rapier-like sharpness of senses.

For him final liberation is to “be in touch with our understanding, our innermost rhythm”.

The sum total of his thinking is given in the final paragraph of the book:

“Each of us has fostered various identities to meet our needs. Our born teacher is buried under these identities. External teachers can never make changes in us. We are our own teacher and student. When we are awakened to or own ‘born identity’, we meet our teacher and from then on, we are taught every minute something new making our life serenely blissful. That is liberation in the literal sense of that word.”

Whether you agree with him on that precise point or not, this memoir will make you ruminate a lot and- I believe- impart a lot of hard-won wisdom as well.

| Book facts | |

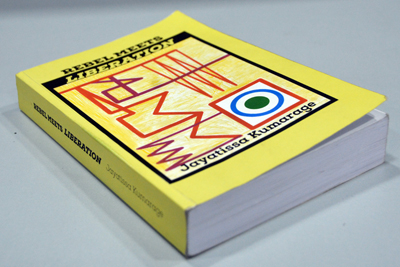

| Rebel Meets Liberation by Jayatissa Kumarage. Reviewed by Yomal Senerath-Yapa |