Chance doc who made a chance discovery

By chance!

By chance!

These are the two tiny words that pepper one of the most important ‘heart’ stories of the 20th century.

It is the story of the discovery of Brugada Syndrome and it is the doctor after whom it has been named, nearly-63 Prof. Pedro Brugada MD himself, seated in the lobby of the Cinnamon Grand Hotel, Colombo, who tells the tale.

Having just arrived in Sri Lanka from Belgium on Thursday to deliver the prestigious Dr. G.R. Handy Memorial Oration at the 15th annual academic sessions of the Sri Lanka Heart Association, the much-sought-after Prof. Brugada, sans even lunch, goes back to the 1990s to talk of his namesake syndrome and also his childhood on a farm in rural Spain.

The memories are vivid of that day in 1986 when a distraught father brought his three-year-old son to Prof. Brugada who was attached to the Maastricht University in the Netherlands. The little boy had gone into cardiac arrest several times and been resuscitated by his father who was a military man, adept at doing so. Earlier, the boy’s sister had died when she was just three years old.

Not only was the father very upset, he was also very aggressive, having already lost his daughter and seeing his son’s life too slipping away similarly. As he screamed and shouted, asking for help, Prof. Brugada and his team which included younger brother Josep did not know what was wrong. When the boy’s father said he was going back to Poland from where the family was, Prof. Brugada had one request. “Bring back your daughter’s medical charts,” he said.

What the two brothers saw sent them into shock. “The electrocardiogram (ECG – used to assess the electrical and muscular functions of the heart)) of the girl was abnormal. We had never seen the likes of it before, except that it was similar to the boy’s ECG,” says Prof. Brugada. Later, they saw similarly abnormal ECGs, with the same problem in the rhythm of the heart, in a Belgian and also a Dutch patient.

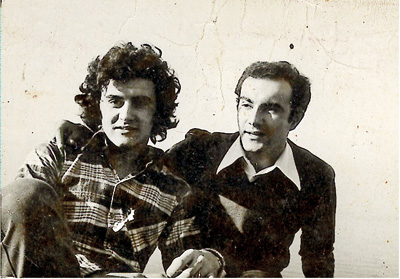

Brothers two: Joseph and Pedro who identified the abnormal heart patterns

These were the findings he presented to the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology (NASPE) in America in 1991, to an astonishing reaction from the many Cardiologists present who had seen similar cases. Although there had been known cases of this “mysterious malady” since 1917, it was brothers Pedro and Josep who picked up the specific patterns in the ECGs.

With four more similar cases, Prof. Brugada published a scientific paper in 1992 on the first eight patients who were victims of this condition, three of whom were children. It was the first description of a new clinical cardiologic syndrome.

Little by little, the discovery gathered momentum internationally with the Japanese, the Thais and the Indians reporting such cases in their countries. In Japan this condition was called ‘Pokuri’ and in Thailand ‘Lai-Tai’, says Prof. Brugada, explaining that it meant ‘suffocate and die in the night’ because the victims usually died in the night, giving out a small sound. In other parts of the world it was called Sudden Unexplained Nocturnal Death Syndrome (SUNDS).

Gradually recognition came and in 1996, it was the Japanese, referring to Prof. Brugada’s scientific paper, who dubbed it ‘Brugada Syndrome’. Looking back 23 long years, he says with humility that although the paper was just three pages “we had put everything in summary in it including the hereditary factor and specifics of the condition”.

Back in the 1990s, more breakthroughs followed for Prof. Brugada and Josep with a few of the milestones being the identification of the first gene (SCN5A – one of a family of genes that provides instructions for the making of the cardiac sodium channel) that causes Brugada Syndrome, with the findings being published in the top medical magazine ‘Nature’, followed by the zeroing-in on 16 more of the 24 genes responsible for the condition.

In the pipeline currently are publications on the balance seven of the 24 genes, says Prof. Brugada.How it all began is clearly attributed to “chance” as Prof. Brugada reminisces about his childhood. Born on August 11, 1952, to the farming couple Ramon and Pepita, life was tranquil in the village of Banyoles in Catalonia, Spain. Soon he had two more brothers, Josep and Ramon, and a sister, Maria Dolors.

His parents were into animal husbandry, making a living from rearing and selling chickens, eggs and rabbits. For the children, the non-school hours were spent helping their parents on the farm and by the time he was 14 years old, Pedro who was earning a little money, wished to quit school and get into full-time farming. His mother, however, was adamant and brooked no opposition. He would continue his education, she told him in no uncertain terms.

Even at 16, Pedro was “not so sure” what line of study to pursue and entering the University of Barcelona at that tender age, decided on both philosophy and medicine simultaneously in the first year. When the marks were announced, he had secured 10/10 for all subjects in medicine. This was a “big surprise”, he concedes, for in school he had not been “that brilliant or impressive”.

As the pianist in the Cinnamon Grand lobby begins to play, Prof. Brugada gives a hearty laugh and we digress into a discussion on his hobbies as a child. Oil paintings of landscapes were his early fascination, moving onto abstracts and also playing folk music on the contrabass, the “big one”, he laughs, with a band.

Academically, meanwhile, when Prof. Brugada, armed with his results, walked out of the university doors, what he did not know was that “a lot of things were about to happen all of a sudden”. Prof. Valdecasas from Pharmacology was at the door picking out to work for him the best and brightest 25, including Pedro, from their batch of 2,500.

Life changed for Pedro, for into the second year of his medical studies there were no more lectures, only hands-on training at the Council for Scientific Research, with the third year devoted to hospital work, spending night and day with patients gaining “enormous” experience.

At 22, he was a doctor, and along with his first wife, began his medical career as a general practitioner in the Pyrenees for six months, before being called back to the university to specialize in internal medicine. With a bent towards blood-diseases such as Leukaemia and Hodgkins, he was veering towards haematology, but it was not to be, “chance” stepping in the way once again.

There was no opening for haematology and he would have to wait a year. His wife was expecting their first child and he had no job, neither did he have money and on hearing that there was a place in cardiology, he changed tack, “just by chance”.

Completing his specialization by the time he was 27 years old in 1979, Prof. Brugada then decided to do ‘extra time’ studying cardiac arrhythmias. With the electrophysiology of the heart being a new field, he headed to the Maastricht University in the Netherlands to learn more about this emerging area. Originally planning to stay six months, he never returned but took up a job there and settled down, rising to the post of Professor of Cardiology with a special interest in heart rhythm disturbances in 1986.

In 1990, he moved to Belgium’s OLV Hospital’s Cardiology Centre in Aalst which had zero-status for facilities to deal with cardiac arrhythmias. “Now Belgium has 32 centres,” Prof. Brugada says with pride, having also trained many a local and foreign doctor. “In 1990, there were only three new implants performed on patients for cardiac defibrillation but now there has been ‘an explosion’ with 2,500 such implants each year.”

It was in 2007 that he joined the Flemish University of Brussels (Uz-Vub Brussels) where he is Chairman and Scientific Director of the Cardiovascular Division. Lamenting that research funding is becoming more and more difficult to come by, Prof. Brugada’s logic and drive is simple.

“Ignorance drives progress,” says this trailblazer who has not only delivered many prestigious lectures but also has many gold medals and publications to his credit. Search for what you don’t know, he urges doctors, for curiosity has to be driven by ignorance. “If a doctor is not curious, he or she cannot become a good doctor.”

It is on a lighter note that we end the interview. Conceding that he is a workaholic, Prof. Brugada who travels extensively across the world and is in Sri Lanka with his third wife, Kristien, a nurse and one of his five children says the way to kill him would be to confine him to a hotel room for three days.

When jokingly asked how his heart is, he looks about hurriedly to “touch wood” in mock superstition and says with a twinkle in his eye, “I’m still alive”.

| What is Brugada Syndrome? It is a common cause of sudden death through cardiac arrest (the stoppage of the heart) brought about by a genetic defect which results in unusual cardiac arrhythmias. Arrhythmias arise when the rate or rhythm of the heartbeat goes too fast or too slow. Brugada Syndrome is treatable by the avoidance of aggravating medications, reduction of fever and if necessary the implantation of the medical device, an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). | |