How do I love thee? Let me count the ways

A few days ago, Luxshman Nadaraja called me and excitedly said that he had photographs and a small video clip, taken in Kumana, of the courtship dance of a pair of black-necked storks. I went to his house as soon as I could and marvelled at the elegance of the pair, as they bowed to each other like Japanese businessmen (as Luxshman said), extended their large wings, flapped these wings, and clacked their beaks with their heads held upwards, all in perfect synchrony. It was mesmerising.

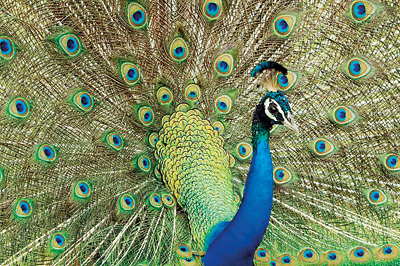

Many animals have ritual courtship behaviour: A peacock fans upright in front of a prospective mate. Pic by Riaz Cader

These stylised displays of courtship are means of attracting a mate, for the ultimate purpose of reproduction. Many, many animals have ritual courtship behaviour, such as the very familiar shimmering, vibrating fan of spectacular feathers that a peacock fans upright in front of a prospective mate. Male zebras chase their mates, male sticklebacks (freshwater fishes of temperate waters) perform a zig-zag dance for females, blue-footed boobies stomp out a sort of hokey-pokey (they put their left foot up, they put their left foot down, they put their right foot up, they put their right foot down) and male butterflies flap their wings in whirr of speed in front of a female.

However, courtship displays that fly off the scales in terms of being jaw-droppingly amazing, are those of New Guinea’s birds of paradise. Each of the 39 species has either spectacular plumage (Greater bird of paradise), a mish-mash of near-fluorescent colours (Wilson’s bird of paradise), strong and lengthy calls (Goldie’s bird of paradise), or bizarre feathers (King bird of paradise). But my absolute favourite is the male Western Parotia, a seemingly drab black bird, albeit with a headdress worthy of Cher. For his dance, he suddenly puffs out a stiff set of feathers that look like a black taffeta skirt, and moves to the right, then moves to the left, repeatedly, as if choreographed by the great Frederick Ashton, all the while shaking his head like a veteran Bharatha Natyam dancer, making the feathers on his head bob.

Why have animals developed such elaborate and ornate forms of courtship display? Why, in some species, are the males so spectacularly and more stunningly coloured, and in effect, more coiffed than females? Darwin explained this as sexual selection — a form of natural selection where those better adapted to finding a mate will reproduce more than others, leave more offspring, therefore leaving their genes to survive.

He observed and noted that sexual selection operates in two ways: male dominance and female choice. In the former, males compete for females by intimidating or defeating a competitor. In the latter, males make themselves more attractive to females, so that females can choose the most beautiful or the strongest.

Both these forms of sexual selection lead to marked differences in sexes — sexual dimorphism. There are characteristics that develop purely for sexual selection — such as the tail feathers in a peacock, or a beard in a man — that are called secondary sexual characteristics.

To secure a mate blue-footed boobies stomp out a sort of hokey-pokey. Pic by Sula Nebouxi

In the case of male dominance, males are much bigger than females and are equipped with weaponry such as horns and antlers, and the biggest and strongest will, indubitably, defeat the weaker male and gain access to females. When female choice is the means of selection, then a male has striking plumage, ornate adornments or precisely choreographed courtship dances, all meant to entice the female to choose him and only him.

In the case of deer, during the breeding season — called the rutting season — males spar with each other, clashing and locking their antlers, pushing and shoving with their heads. The male who is stronger and has more endurance wins and ‘gets the girl’, or in the case of deer which live in herds, ‘the girls’. There may be cuts and bruises, but the fight is not to death.

Kangaroos live in groups called mobs led by a dominant male called a boomer. Males are much bigger than females. Dominance between males is established by a combination of boxing, wrestling and potentially lethal kickboxing that can disembowel an opponent. The dominant male then has sole access to all females in the mob.

The famed King of the Jungle — the lion — is a truly a spoilt king, who lies around lazing in the sun, while the females in a pride kill and bring back food, which he gets to first. He is the master of a pride of females. But waiting in the wings so to speak, are coalitions of two or three young males, eyeing his females. When they attack, they use their deadly teeth to stab and jack knife claws to slash their opponent. The loser skulks away and the winner takes all. But not before, horrifically, he kills all cubs and sub adults who may have been sired by the former king, ensuring the perpetuation of only his genes.

The male elephant seal has the most extreme sexual size dimorphism, with males five to six times heavier and larger than females. In this example, males weighing some 2,300 kilogrammes, meet each other, raise their heads and hoot as a prelude to a nasty, no-holds-barred slamming of their immense bodies against each other, bellowing, repeated biting, until the sea around them turns red with blood and the vanquished male slides off into the sea. The victor will now become a harem master of some 100 females.

Courtship is much more peaceful in the case of female choice. Here, a female chooses a mate for a reason: the male seems fitter, more beautiful or maybe is an excellent provider. In the case of the blue-footed boobies mentioned earlier, which are found in the coastal areas of the eastern Pacific, the blue colour of their feet comes from pigments that are obtained from their diet of fresh fish, mainly sardines. In older males this blue fades. The booby with the bluest feet, is, therefore, usually young and well fed: i.e., strong and healthy. Thus, the courtship dance of the blue-footed boobies has evolved to display the very characteristic that reveals their fitness.

The long-tailed widowbird of Africa has a tail that is some half a metre long, about twice the size the bird. Malte Andersson and his colleagues tested Darwin’s theory of sexual selection by female choice by cutting the tails of some birds and gluing these cut pieces onto others, and showed unequivocally that females choose males with the longest ‘supernormal’ tails.

Sage grouse, found in the prairies of western United States north America, congregate in leks (a collection of displaying males), defending a small territory within the larger space and display for the females — strutting, fanning their tail feathers, puffing their chests and making peculiar puffing and whistling noises. They do this for hours on end. Here, it appears that females choose endurance as a sign of fitness.

The bowerbirds of Australia and New Guinea, on the other hand, are good providers. The satin bowerbird builds a bower for his prospective mate, displaying his architectural skills and then decorates it with various objects such as berries, flowers, shells, drinking straws, keychains and bits of plastic. As David Attenborough says, bowerbirds are ‘passionate interior decorators’ who place each object neatly within each bower. Females choose the most decorative and neatest nest, and preferentially select bowers with the most blue objects. Studies have found that females reject untidy bachelor pads with little blue, so as males mature, they decorate the bowers with more blue.

I shall resist the temptation to draw parallels of the above with human behaviour, and focus instead on what is happening to these amazing, living examples of Darwin’s theory of sexual selection. As with the many other species worldwide, many of these species are also faced with a range of human-induced threats.

Sage grouse and birds of paradise are threatened with habitat loss. Between 2007 and 2013, the number of sage grouse males halved in the US. Sage-grouse need large tracts of undisturbed sagebrush (hence their name) habitat within America’s prairies to live and areas in which to display, and these habitats are being destroyed by various anthropogenic actions — such as wildfires.

Between 1972 and 2002, a substantial amount — 15% — of Papua New Guinea’s tropical forests were clear-felled, while 8.8% were degraded through selective logging. Currently, a further 15% is being degraded. In addition, historically, the weird and wonderful feathers of many birds of paradise have use in tribal ceremonial dress. But now, there is an added layer of illegal smuggling of these birds. So these birds of paradise are not only affected by habitat loss but also by overexploitation.

Satin bowerbirds are threatened by invasive alien species in Australia. Non-native feral cats and foxes prey on these birds which build their bowers on the ground and thus, are easy prey. In addition, the habitats in which these birds live — rainforests of the eastern coast of Australia — are also under threat from the axe.

A most alarming trend has been observed among the blue-footed boobies of the Galapagos. The population has dropped by two thirds from the 1960s. Biologists have found out that only a few pairs of this diminished population reproduced and that there were no juveniles. What the biologists also found was that this decline in breeding coincided with a drop in the populations of sardines, which the blue-footed boobies ate. Hungry blue-footed boobies means unfit blue-footed boobies, boobies with not-so-blue feet. Ergo, their hokey-pokey dance is now rarely seen.

What is scary is that species such as sea lions are also affected by the decrease in the availability of sardines. Species such as blue-footed boobies and sea lions are predators, and their role in these coastal food webs is to keep down populations of smaller predators and herbivores. With some predators dwindling, the whole ecosystem shifts and changes, in ways that we cannot predict. There may be a domino effect of extinctions of which we will know nothing.

The examples presented in this essay are stunning, weird and wonderful icons for Darwin’s theory of sexual selection. But they are sending us a clarion call for conservation action for their species and others around them.