Built to please

Partying is a part of the scene in any chapter of the life of Ceylon or Sri Lanka, as it is a part of the Ceylon/Sri Lanka chapter in the life of Ulrik Plesner, the modernist Danish architect who lived here from 1958 to 1967 and worked with architect Geoffrey Bawa. The architect’s recently published memoir, “In Situ”, is, in fact, built solidly and entirely on Sri Lankan terrain. Those busy, highly productive nine years in Ceylon constitute the content of the book, which has been glowingly reviewed in The New York Review of Books and The Architectural Digest. The reviewers also note the party element in Plesner’s depiction of the Sri Lankan way of life.

So a party was only to be expected when Ulrik Plesner came to town recently to launch and sign his book.

Revisiting an old chapter: Plesner at Barefoot last month

We sat in the garden of the Barefoot Gallery as the architect chatted with local architect and art lover Ismeth Rahim and images from Plesner’s book and scenes pertinent to the art and architecture of 20th century Sri Lanka flashed on a large projection screen. The discussion wove through and around Plesner’s “architectural memoir” and the people he worked and moved around with in those colourful Ceylon years.

When he arrived here in 1958, Plesner, now 83 years, was in his late thirties, a young and strikingly good-looking, eye-catching Nordic visitor – blond and blue-eyed. It was in reference to his “piercing blue eyes”, in fact, that we first heard Ulrik Plesner’s catchy name. It was during a lunch conversation at the Dickman’s Road home of Doreen and Ivers Gunasekera. Doreen Gunasekera vividly remembered the penetrating effect that Plesner’s eyes had on people. (Plesner was a friend of the Gunasekera family; cricketer C. I. Gunasekera’s brother Dallas and Dallas’ Italian artist and sculptor wife, Lydia Duchini, appear in the book, in both text and photographs. To underline the closeness of the community described in “In Situ”, we might mention that Dallas Gunasekera and Geoffrey Bawa were classmates at Royal College, Colombo, in the Forties.)

The name Ulrik Plesner would come up in conversation, and each time it rang in the ear with a resonance you hear in many architecturally renowned names, such as Nicolaus Pevsner (the art and architecture historian), Le Corbusier, Luis Barragán, and even our own Geoffrey Bawa. Architects – the famous ones – seem destined to have reverberant names.

Skimming through “In Situ”, you get the impression of Ulrik Plesner the architect as a forward-looking visitor, his feet firmly planted on local ground and head held high and alert to local colour and local possibilities. As a writer, he is talented and hugely entertaining. The prose flows and the stories fly, while names are dropped – big, small, familiar, unknown – like paddy seed spilling from a farmer’s hand. To a Sri Lankan, the book should be an occasion for instant recognition and delight.

The book is a portrait of Sixties Ceylon as lived by those who loved and practised the visual and plastic arts, and who strove to protect and preserve the country’s fragile and fast fragmenting architectural and artistic heritage. This close-knit community was led by the likes of artist and designer Barbara Sansoni, sculptor and artist Laki Senanayake, and pioneering architect Minette de Silva.

“In Situ” has been described as a “good holiday read”, which is not always the case with architects’ memoirs, as the reviewers point out.

The conversation between Ulrik Plesner and Ismeth Raheem elicited interesting insights from Plesner. The Dane’s take on architects and architecture can be startling. He is not impressed by all that is iconic; the Sydney Opera House and New York’s Guggenheim Art Museum, for example, are functional failures, for all their daring, avant-garde looks. Much of modern architecture is done for effect, with scant regard for actual practical usage. “Many of the people who live in fancy houses designed by famous names hate their homes!” Plesner declared. “These are structures that simply don’t work. They are for looking at, not living in.”

Plesner was full of praise for Geoffrey Bawa, but intrigued by what class and privilege had done to him. “Because of his elite family background, Geoffrey never in all his life had to do anything for himself, anything menial, like picking up a pencil or a sketch that had fallen on the floor. That had to be done by others.”

As an architect, Bawa saw himself essentially as a conceptualiser, according to Plesner, and the tasks of physically creating designs and buildings were for “others to do.” Plesner claims that it was he who taught, painstakingly, Geoffrey Bawa to use the tools of the architect’s trade. “Geoffrey did not know how to use a T-square until I showed him.”

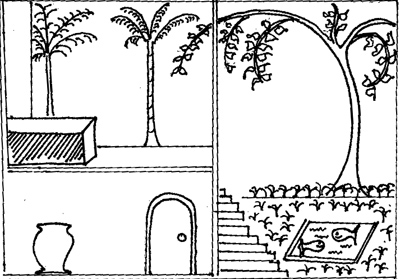

A stylised imaging of the Plesner building the writer had visited some 40 years ago

Plesner’s early training as an architect included brick-laying and carpentry and all the rough nitty-gritty of physically piecing together and cementing a building. He said he was glad that today’s architects, most of them trained to use the computer to make designs, were now seeing the necessity to go back to the blueprint and hands-on era in their apprenticeship.

The evening’s host, the photographer Dominic Sansoni, said his family owed much to Ulrik Plesner, who, in the early Sixties, designed a structure that was built in the back garden of the Sansoni residence in Anderson Road, Havelock Town. “We lived in this building, I grew up there,” he said. “It is the scene of my childhood, teenage and present life. It’s a part of the family life. And it was the scene of many, many memorable parties.”

We were present at one of those parties, in 1973. It was a farewell to Stefan Abeysekera, the well-read, long-haired guru in our largely beatnik group. Stefan, son of Government Agent Vernon Abeysekera and singer Lorraine (nee Forbes), were migrating to Australia. At 14 years, Dominic Sansoni was the youngest in a large posse of Havelock Town-Bambalapitiya-Kollupitiya rock-music lovers and Beat poetry fans. Stefan, Mohan, Baalu, Thambi, Georgie, Michel, Mervyn and the rest were in their late teens, early Twenties. We had all visited the Sansoni residence and were in awe of the avant-garde structure at the back of the house. None of us had seen anything like it.

It was a two-tiered square with an adjoining terrace and fishpond. The ground floor was a live-in unit occupied by a foreign guest who was away at the time. All we could see of the ground-floor interior was what was visible through a window facing the back boundary wall: a bedroom and a bathroom connected in a novel way, the bed set right next to the bathtub, so that on waking the bed’s occupant could slide over into the tub for his morning bath. Interesting and daring, we thought.

We then climbed a flight of unprotected stairs on the other side of the square to the upper floor. Here was something even more interesting and daring: a large living space with a high roof and on three sides utterly open to the elements. In one corner was a solid, rectangular bed-base, a slab of immovable white-washed brick, with a short ledge running alongside.

You sprawled on the bed, listened to “Jesus Christ Superstar”, and enjoyed a 180-degrees view of gardens, housetops and even sky. And you had all the natural light and air you could ask for. Here was a place where you could wake up to find a rilawa sitting at the foot of your bed or a sparrow hopping on your pillow. It was a futuristic bedroom for the tropics and for very progressive, artsy people. We who had spent our indoor lives hemmed in by brick walls and locked doors would have a hard time surrendering to sleep in such a wholly open and vulnerable setting. This was the bedroom of the teen Dominic Sansoni.

All evening, all night the guests came and went. The lights blazed and the music rocked. We went up stairs and down; spread out on the solid brick bed or the paved-grassed terrace below; gazed down at the goldfish or up at the stars; raised glasses and dropped names and words like Huxley and Ramakrishna, Utopia and Existentialism.

In the morning the party folk drank coffee, rubbed their eyes and slowly filed out of the Plesnerian environs. We walked up Dickman’s Road and broke up when we reached the Galle Road. Pleasure, Plesner, Party, Arty – all these elements and more had flashed and fused in an explosion of colour in our heads.

comments powered by Disqus