News

Blaming and shaming or learning from errors the way out

View(s):Reducing medical misadventures

By Kumudini Hettiarachchi

Doctors are under the microscope with headlines highlighting two separate incidents of a hand-amputation and a death of a child allegedly linked to preparations before an MRI scan. This brings to the forefront not only issues of patient safety but also whether there should be a “naming, blaming, shaming culture” or learning from errors, said a cross-section of doctors that the Sunday Times spoke to.

“It is difficult to believe that a doctor would wilfully cause harm, injury or death to a patient,” said a senior doctor who declined to be identified. However, medical errors have happened, will happen and continue to happen in the future, stressed another doctor, explaining that tragic though the harm or death is, unlike in any other profession it creates ripples because human life is involved.

Medical errors are complex issues, but error itself is an inevitable part of the human condition, said Dr. Rathnasiri Hewage, Director of the Lady Ridgeway Hospital for Children, Colombo. “Learning from the error is more productive and a ‘root-cause analysis’ (RCA) is vital to prevent and ensure non-recurrence.”

He urges that there should be acceptance that errors can and will occur; assess the local “bad stuff” before embarking upon a task; be ready to deal with anticipated problems; be prepared to seek more qualified assistance; and not let professional courtesy get in the way of checking a colleague’s knowledge and experience.

The RCA, according to him, focuses on prevention, not blame or punishment and also looks at system-level vulnerabilities rather than a person’s performance. At the system-level would come communication; training; fatigue/scheduling; environment/equipment; rules/policies/procedures; and barriers.

Under the RCA model there is a rigorous confidential approach to answering: What happened? Why did it happen? What will we do to prevent it from happening again? How will we know our actions improved patient safety?

Pointing out that in the late 1990s the report, ‘To err is human: Building a safer health system’ by the Institute of Medicine, USA, found that nearly 100,000 people in the US died per year due to medical errors, he said that it prompted the launching of the World Alliance for Patient Safety in 2004. Here the World Health Organization (WHO) along with experts and patients’ groups came up with the goal of ‘First do no harm’ and announced key actions to cut the number of illnesses, injuries and deaths suffered by patients during healthcare, the Sunday Times learns.

Asking “what is error”, Dr. Hewage quotes a simple definition as “doing the wrong thing when meaning to do the right thing”. In contrast, a “violation” is a deliberate deviation from an accepted protocol or standard of care.

Errors could be:

- Skill-based slips and lapses – attentional slips of action or lapses of memory

- Mistakes – rule-based mistakes or knowledge-based mistakes

“Regardless of experience, intelligence, motivation or vigilance, people make mistakes,” he says, adding that situations associated with an increased risk of error are unfamiliarity with a task; inexperience; shortage of time; inadequate checking; poor procedures; and poor human-equipment interactions. This would get aggravated if combined with lack of supervision.

Meanwhile, limited memory capacity which could be further reduced by fatigue, stress, hunger, illness and hazardous attitudes could lead a doctor to err, it is learnt.

It is important to monitor incidents that harmed or could have harmed a patient and learn from that. This would help identify recurring problems, known as ‘error traps’ and remove them, he added.

Sick child needs trained anaesthetist

A child is not a small version of an adult, reiterates Dr. Premaratne, pointing out that “smaller the child or sicker the child”, there is a need to have a more experienced anaesthetist to take care of the child. For, a child could become destabilised very easily and become hypoxic (deprived of oxygen) due to airway problems.

When asked about the training of anaesthetists, he said that in Sri Lanka all anaesthetists get a mandatory training of six months (full-time) in anaesthesia under a consultant anaesthetist. During this period, they would get reasonable exposure to anaesthetising children.

A consultant anaesthetist in Sri Lanka will have a minimum of six years of post-graduate training in anaesthesia, intensive care and pain management, he added.

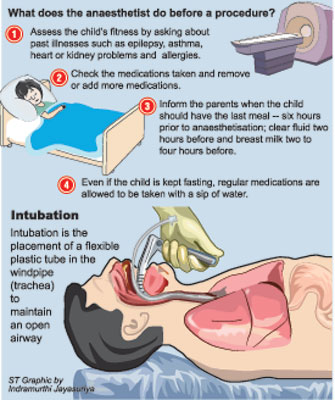

Procedure before an MRI scan

With the parents of Buddhini Kaushalya Ratnayake alleging that something happened to her in the MRI scanning room and Nawaloka Hospital categorically stating that the MRI machine was not switched on, the Sunday Times asked Consultant Cardiothoracic Anaesthetist Dr. Mithrajee Premaratne of the LRH to detail the procedure before a child undergoes an MRI scan.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a painless test inside a special machine that contains a strong magnet that uses a magnetic field and pulses of radio wave energy to make pictures of organs, in Buddhini’s case it was the brain. Sedation or anaesthesia may be utilised to keep a child still during this test, the Sunday Times learns.

Sedation is when a child is given medicine to make her feel sleepy to prevent becoming distressed when having a test. Procedural sedation (sedation for procedures) aims to reduce the child’s anxiety and should be provided by a trained anaesthetist, said Dr. Premaratne. Anaesthesia, meanwhile, is a state of controlled unconsciousness produced by special medications and gases that have temporary effects on the brain and other organs of the body.

An older child may not need sedation if she can stay still, while an anxious younger child may have to be sedated, so that she will sleep during the MRI scanning. The medicine for sedation may be given by mouth (to drink), by breathing-in a gas or by an injection into a muscle or a vein. When sedated, other than monitoring the child’s vital signs, only oxygen is provided via a face mask. If the procedure takes longer or needs a deeper level of sedation, the child may be intubated, it is understood.

When a child is sedated outside the operating theatre, like in a scanning room, special preparation and attention should be paid as it is not done routinely in this environment, it is learnt. Meanwhile, there are two ways a child may be anaesthetised, according to Dr. Premaratne. They are:

·Giving the anaesthetic intravenously or medication through a vein to induce sleep and inserting a tube called a laryngeal mask airway (LMA) through the mouth to the throat to sit above the larynx and vocal cords. This may be a preferred technique by most anaesthetists. Here the child does not need to be given a muscle relaxant and breathes on her own.

·Giving intravenous medication followed by a muscle-relaxant (where the child is paralysed and cannot perform breathing on her own). Then a tube is passed through the mouth and vocal cords into the windpipe (trachea). This process is called intubation (see graphic).

Thereafter, if the muscle relaxant is continued, as the child cannot breathe on her own, the child is either manually ventilated by connecting her to an inflatable bag with a breathing circuit which is operated manually or artificially supported by connecting her to a ventilator. If in these two instances something goes wrong with the equipment, then an ambu bag is used to push air into the breathing circuit as the child cannot breathe on her own.

If the muscle relaxant is not continued after intubation and the test is a short one, the child may be connected to the inflatable bag with the breathing circuit and allowed to breathe on her own. In this case even if the tube comes out accidentally, the child can breathe on her own while oxygen is being provided through a face mask.

For both sedation and anaesthesia, informed consent needs to be obtained by the parents.

During the MRI, the child would be monitored using clinical skills as well as MRI-compatible monitoring equipment such as pulse oximeter for oxygenation; blood pressure; ECG for electrical activity of the heart; and capnography for carbon dioxide removal.

When the procedure is complete, the anaesthetist turns off the anaesthetic agents and skilfully reverses the effects of the medications.

Kaushalya died at the SICU, not inside MRI scanner: Paediatrician

Five-year-old Buddhini Kaushalya Ratnayake died while undergoing treatment at the Surgical Intensive Care Unit (SICU) of the Nawaloka Hospital, and not in the MRI scanning room, said paediatrician Dr Duminda Pathirana at the Colombo Fort Magistrate’s Court. Giving evidence at the inquest on the child’s death, Dr Pathirana told Colombo Fort Magistrate Kanishka Wijeratne that the child was then taken to the SICU, where she was treated for an epileptic fit. The fact that she had an epileptic fit was also indicative that her brain was functioning, and she was alive, Dr. Pathirana testified.

However, he could not say exactly whether the epileptic fit caused the child’s death. Dr. Pathirana told court that he had treated the child earlier, and she was admitted to the hospital on January 31, when she was diagnosed with Rett Syndrome. Following discussions with several other neurologists, he referred her for an MRI Scan.

While he was attending to patients at the OPD, he was informed that this child was in a critical condition. He also said that, later her heart beat was restored and she was treated at the SICU.

According to Dr. Pathirana, the child was alive when she was taken out of the MRI room.Earlier, the victim’s mother alleged that her daughter died while undergoing a MRI scan, due to negligence of the hospital staff. The child was pronounced dead on the evening of February 6, due to brain and heart failure. The Kompanna Veediya Police led evidence. The inquiry was in sequel to a complaint made to the Police by Kaushalya’s father.Counsel Raveendranath Dabare with Rushanka Samaranayake appeared for Kaushalya’s parents.A team of lawyers led by C.R. de Silva P.C. appeared for the Nawaloka Hospital. Further inquiry was put off for March 11.

Follow @timesonlinelk

comments powered by Disqus