When we refer to the interaction of India and Sri Lanka in whatever field, we assume that India and Sri Lanka are two separate countries, but there was a time in the distant past when India and Sri Lanka were a single land mass. Even today after the land mass has split, the distance between India and Sri Lanka is only 22 miles. That is the full distance of the Palk Strait.

In earlier ages when transport and communications between countries and contacts were minimal, the only significant foreign impact on Sri Lanka was that of India. Of course, everybody knows that the greatest gift to Sri Lanka from India, is Buddhism. The religion, which originated in India but was superseded there by Hinduism and Islam, was brought across to Sri Lanka in the 3rd century B.C. by Rev. Mahinda, the son of Emperor Asoka of India, who founded the order of monks here. He was followed by his sister Sanghamitta Theri, who founded the order of Buddhist nuns here. The arrival of Rev. Mahinda in the 3rd century B.C. is recorded in the Mahavamsa, the Great Chronicle, and substantiated by a rock inscription after his passing away, found in Amparai.

Buddhism is the fountainhead of Sinhalese literature.

Pali texts brought by Rev. Mahinda were translated to Sinhalese and designated the Hela Atuva. These texts were translated back into Pali by Rev. Buddhagosha, who came from India in the 5th century. The Sinhala texts were destroyed and Pali became the official language of Buddhism. The earliest extant prose works of importance in Sinhalese date from the 13th century and were pietistic – the Amavatura of Gurulugomi, the Butsarana of Vidyachakravarti. Of special significance for the development of the short story were Dharmasena Thera’s 13th-century Saddharma Ratnavaliya and Saddharmalankaraya (1398-1410) by Dharmakirthi Thera II, based on earlier Pali texts.

|

| The writer stands in front of Akbar the Great’s Palace in Fatehpur, Sikri |

It has been observed that the Saddharma Ratnavaliya and the Saddharmalankaraya combine an ever present moral and religious didacticism with a surprisingly rich, earthy yet subtle vein of psychological exploration dealing with emotional impulses and social pressures that govern daily life. The Jataka tales (stories of the past lives of the Buddha) which were recorded in the 14th century and were popularized by monks who used these to illustrate their sermons, form a part of a popular oral tradition. These contained the rudiments of fiction which influenced the rise of Sinhalese fiction as from the late 19th century, as well as stimulated later literary works.

The Sinhalese during the long years before the impact of Western literary criticism were indebted exclusively to India, to Sanskrit in particular, for literary touchstones – for ideas as to what constitutes literature, for ideas as to how to appreciate and evaluate literature. The touchstones include alankara (embellishment, decoration), shailya (style), reethi (rules, standards), guna (inherent quality), vakrokti (indirection, obliqueness), rasa, auchitya (suitability, appropriateness) and dvani (denotation and connotation). In the 9th century, King Sena’s Siyabaslakara was more or less a translation of Dandin’s earlier Sanskrit work Kavyadarsha which discussed general issues and poetic figures.

Sri Lanka also inherited literary forms from India. Sanskrit drama was, probably, read but was never performed and did not provide a stimulus to local playwrights. On the other hand, Kalidasa’s Mega Dutha or Cloud Messenger inspired a whole host of Sinhalese sandesa or message poems such as the Mayura Sandesaya (the Peacock Messenger Poem) and the Tisara Sandesaya (the Swan Messenger Poem). It is interesting to note that among the Sigiri Graffiti is a Sanskrit sloka written by a visitor from India called Vajira Varman, responding to the frescoes.

It is interesting to note that Sanskrit was not only a seminal influence on the arts in Sri Lanka but that Sri Lanka made a contribution to Sanskrit literature itself by means of a poem named the Janaki harana which has for its subject the story of the Ramayana. Manuscripts of the poem found in the 1950s in Malabar proved that the poet of the Janaki harana was indeed named Kumaradasa. He was not a king but a scion of the Sinhalese royal family, the son of a prince named Manita.

Tamil literature in Sri Lanka lay in the shadow of South India for a very long time, and a distinctively Sri Lankan kind of Tamil literature was unable to emerge until the 17th century. As purist scholars on both sides of the Palk Strait endeavoured to follow a South Indian and Sanskrit tradition, the first Sri Lankan Tamil literary works were written in a religious spirit, the spirit of Hinduism which was another great gift from India. These were confined to commentaries on the ancient classics, tedious and conventional. The first spark occurred in the late 19th century as a consequence of religious zeal and conflict. Christian missionaries sought to proselytize by preaching in the native language, and they enlisted traditional poetic forms to express Christian themes. On the other hand, to combat the inroads of missionaries, Hindu poets created works which explicated and exalted their own religion. This literature too was of a didactic sort.

The South Indian film and dance forms like Bharata Natyam, Kathak and Kathakali continue to exert a potent influence on Tamil mass entertainment and art in Sri Lanka, but the winds of change in Sri Lanka in the 1950s made a deep impact on Tamil writing – fiction, poetry and drama – and brought about a Tamil literature that broke free from South Indian literature and assumed a distinctively Sri Lankan identity. Tamil writing became irrevocably secular and popular in character. Nevertheless the South Indian influence was a catalyst. It should also be observed that dance forms like Bharata Natyam, Kathak and Kathakali have interested Sinhalese performers and audiences.

In the 20th century, among the Indian individuals who exerted an influence on Sri Lankan culture, the greatest was Rabindranath Tagore. He is the only Indian to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, a hallmark of world recognition, and the creator of the song in Bengali which was adopted as the national anthem. In his Bengali essays, Tagore stresses that the Bengali word for literature, “sahitya”, derives from “sahit” and etymologically means together or intimacy.

Tagore was not chauvinistic. He emphasized that an India, bereft of Western contact, would have been wanting in an essential element in her quest for fulfilment. Like Jawaharlal Nehru in The Discovery of India, Tagore believed that the greatest blessing of British rule was that it enabled the heterogeneous country that was India to rise in a single voice, the Indian voice. Tagore expresses his view of freedom:

Where the mind is free,

and the head is held high,

where knowledge is free;

Where the world has not been broken up

into fragments by narrow domestic walls.

Tagore seems to me the quintessential Indian.

As commonly in ex-colonies, the presence of the colonial ‘masters’ had a suffocating effect on the creative energies of the local inhabitants in Sri Lanka and the emergence of Sri Lankan English literature flows from the growth of nationalist currents. This growth was stimulated by the freedom struggle in India and by certain remarkable Indians who were active in that period. In the 1930s and early 1940s, the Kandy Lake poets were inspired by Indian poets such as Tagore and Sarojini Naidu. R.K. Narayan’s success in the West is likely to have stimulated Jinadasa Vijayatunga. D.F. Karaka was a household word in Sri Lanka at that time; his fiction and non-fiction would have acted as a stimulus to local writing. S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike attended a performance of Tagore’s Saapmochan which Tagore himself staged in Colombo during a visit to Sri Lanka in 1934, and Bandaranaike wrote in his review (which included a quotation from Sarojini Naidu’s poetry):

India has as good a reason to be proud of Tagore as of Gandhi; for he has made an original contribution to art which can stand the test of comparison with anything of the kind the West has evolved.

Ediriwira Sarachchandra (1914-1996), a remarkable bilingual, became the pre-eminent man of letters in Sinhala as well as the leading novelist in English. Some of his formative influences were Indian. When he was a schoolboy at St. Thomas’s College in the 1920s and early 1930s, he came into contact with Tagore, a collection of whose short stories was a prescribed text at the College. The mysticism of Gitanjali made a deep impact on Sarachchandra.

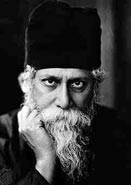

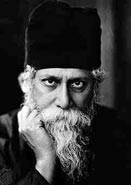

|

| Tagore: The quintessential Indian |

He read of Tagore, and of Santiniketan, the institution Tagore had founded in Bengal, where the life led by the teachers and students accorded with Tagore’s credo of ‘high thinking and plain living’ and seemed to Sarachchandra ideal. When Sarachchandra was a student at University College, Colombo, he saw at the Regal Theatre a performance of the same Tagore dance drama which Bandaranaike did, and recorded his experience:

During the ballet we saw the great poet Rabindranath Tagore seated on stage,

keeping time with his foot to the rhythm of the music, and savouring the

pleasure given by his creation. In his long robe and black headgear, with white

hair flowing on either side of his face and a beard that covered his chest, he

was an impressive individual with an aura of majesty about him. To see him in

the flesh was happiness of a sort I had never hoped for.

Shortly afterwards, Sarachchandra witnessed Uday Shankar dance, with his troupe, at the same theatre. Sarachchandra became enchanted by Bengali music and dance, which he identified as a part of his cultural heritage, and desired to go to Santiniketan to study it. He succeeded in doing so. When he returned to Ceylon from India in 1940, he was a transformed man. He gave up Western dress for the Indian kurta. He was employed for a while as a Sinhala teacher at S. Thomas’ College. The young westernized students there found him amusing and nicknamed him ‘Tagore’, which Sarachchandra considered a compliment.

Wilmot Perera was inspired by Tagore’s Santiniketan and his association with Tagore himself to found Sri Palee in Horana as a school for music, dance, the fine arts and allied subjects. Perera felt the British system of education in Sri Lanka at that time did not suit Sri Lankans and he favoured traditional learning. He modelled Sri Palee on Santiniketan and followed Tagore’s system as practised there. In fact, Sri Palee was launched by Tagore himself in 1934. In the past 20 years, translators into Sinhala have shown a remarkable interest in Indian literature, both the literature in English and the literature in the vernacular languages.

Bobby Boteju believes that one should know the literatures of neighbouring countries before one ventures further afield. He has devoted himself to translating Indian short stories and translated over one thousand of these. He was the first to introduce R.K. Narayan to the Sinhala reading public by translating Malgudi Days in 1991. He has translated stories by C. Rajagopalachari, the first Governor General of India after Independence, and stories by Asokamitran, originally written in Tamil; stories by Premchand, originally written in Hindi; stories by Takazi Sivasankar Pillai, originally written in Malayalam; stories by Tagore, originally written in Bengali; and stories by numerous other writers.

Translations into Sinhala from the Indian vernacular languages have been usually done via English renderings, but Chinta Lakshmi Sinharachchi has translated Indian vernacular literatures directly from the original languages, Bengali, Hindi and Urdu. She has translated Tagore’s Gora from the Bengali, Premchand’s Godani from the Hindi, Chattopadyaya’s Aranayak from the Bengali, the original texts of Satyajith Ray’s trilogy, Apparajitho, Pather Panchali and Apu Sansar. Among the Indian writers in English, R.K. Narayan has been a favourite among translators into Sinhala: W.A. Abeysinghe has translated Swami and Friends; Kulasena Fonseka The Painter of Signs; Milroy Dharmaratne The Dark Room.

All the translations from Indian literature have been well received by the Sinhala reading public, probably, because of their relevance, given the similarities and links between the Indian environment/culture and the Sri Lankan. It is perhaps too early to think in terms of their impact on creative writing in Sinhala. But there are already signs of influence.

During the Kandy period, the phase before British rule in Sri Lanka, the Sinhalese kings brought wives from South India. As a consequence, Carnatic music entered Sri Lanka. In more recent times, earlier Sinhala drama such as the nadagam and nurti use Carnatic music.

Marris College of Music, later named after its founder as the Bhathkande College of Music, at Lucknow has been, and still is, the Mecca for oriental musicians from Sri Lanka. Sunil Shantha, Lionel Edirisinghe and V.S. Wijeratne, all studied there. On his return, Sunil Shantha became the first popular artist in Sinhala music. Amaradeva, who was Sunil Shantha’s violinist, took off from where Sunil Shantha left. He adopted a North Indian style and infused an increased musical content into his songs. Before Sunil Shantha, Sinhala music as practised by Sedris Master and Rupasinghe Master was based on Raghadhari music.

The music of popular Sinhala films was often provided by Indians such as Naushad or copied from India by Sri Lankan singers such as H.R. Jothipala. Sri Lankan popular Sinhala films were, and still are, influenced by South Indian cinema/Bollywood. Indian teledramas dubbed in Sinhala and Hindi songs are popular fare on local television channels.

George Keyt is undoubtedly Sri Lanka’s most famous painter. The dominant influences on his art were Hindu mythology and literature. Keyt’s sensuous, stylized art, in turn, had a great impact on younger painters.

The profound influence of India on Sri Lanka in the field of culture has been underpinned by political and economic links. The Sri Lankan Independence movement drew inspiration to a certain extent from the Indian Independence movement. There was cooperation between the Indian National Congress and the Ceylon National Congress. Delegates from Ceylon such as S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike addressed sessions there, while delegates from India such as Gandhi and Nehru addressed sessions here. It was mainly as a consequence of the militant freedom struggle in India that the less militant Sri Lanka won its independence.

In the sphere of economics, India is currently Sri Lanka’s biggest trading partner. In addition to normal trade, there is a Free Trade Agreement between the two countries. India is one of the major investors in Sri Lanka.

The interaction of India and Sri Lanka in every sphere – cultural, economic, political – is now more intense than ever before, while at the same time both countries are more open to influences from other countries as well. Perhaps Mahatma Gandhi has suggested the final wisdom in this context:

“I do not want my house to be walled and my windows to be stuffed. I want the culture of all lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible, but I refuse to be blown off my feet by any one of them.”

D.C.R.A. Goonetilleke’s recent books include “Salman Rushdie: Second Edition” (Palgrave Macmillan), “Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness” (Routledge) and “Kaleidoscope: An Anthology of Sri Lankan English Literature.” |