Some books never leave you. You remember when you first read them, who gave them to you, which passages gripped you and which parts left you misty with emotion. I was 14 when my mother gave me her treasured copy of ‘Gone with the Wind’, its binding coming apart, carefully enclosed in thick brown paper. And it has stayed with me.

The trip to 990 Peachtree Street on July 4, 2009 -so many years later was thus more than sheer nostalgia. On that sunny sloping street, with Atlanta’s high rises casting their long shadow over the neighbourhood, there was a palpable sense of history. For in a tiny apartment on the ground floor of the three-storey red brick house built in Tudor style was ‘where it all began’.

Its most famous inhabitant called it ‘the Dump’. Originally built in 1899 as a home for one Cornelius J. Sheehan, the house was turned into an apartment building with ten units in 1919. Margaret Mitchell and her second husband John Marsh occupied Apartment No 1 of what was then Crescent Apartments in the 1920s and this is where she wrote Gone with the Wind, that enduring American epic of love and survival against the tumult of the Civil War.

|

Southern belle: Vivien Leigh as Scarlett O’Hara. Bottom - Free spirit: Margaret Mitchell |

|

What began there to while away the long days of a young woman laid up by illness went on to become one of the most loved books of all time, a best-seller that ranks second only to the Bible.

But Mitchell, rebellious daughter of an aristocratic Georgian family was herself a stubborn individual whose life story is every bit as fascinating as the wilful heroine of her book.Margaret Mitchell lived in Peachtree Street for the better part of the writing of the book and today her former home is a museum open to visitors.

A narrow doorway leads to the ubiquitous gift store where pictures of Vivien Leigh’s luminous beauty as Scarlett O’Hara are paired with a rakish Clark Gable as Rhett Butler. There is stuff aplenty for the souvenir hunter-- music boxes, porcelain plates, books and postcards.

Tickets duly obtained (we are lucky, being American Independence Day- it’s free) a guide escorts little groups of ten to 15 at a time through the apartment and what unfolds is the story of a tiny but spirited woman (she was barely five feet tall) who having imbibed the Southern landscape from her childhood found expression in her writing for all the complexities and contradictions in her nature and upbringing.

Gone with the Wind was written when Margaret was nursing an ankle injury and unable to work. Her solicitous husband regularly brought her piles of books from the local library but she went through them at such a pace that he is said to have told her ‘Peggy, if you want another book, you’ll have to write your own’. She did.

The piles of paper grew as she typed furiously on her portable Remington, secreting them from view in a stack of manila envelopes. She was notoriously loath to share her writing and when friends dropped by she would hide the heap under towels, divans, even under her bed. It helped no doubt, that she had a vast storehouse of knowledge of her subject, having been regaled with tales of the war from childhood, with her grandfather Russell Mitchell having been a doughty veteran of the Civil War himself.

The little apartment, just a few rooms is carefully furnished in the style of the times but disappointingly houses nothing of Margaret’s own personal effects. Like the town in which it was set, the house, has been through fire and ruin. It was maintained as an apartment building until 1978 when it was rescued from dereliction by a group of conservationists intent on preserving the writer’s legacy. Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young named it a city landmark. Tragedy struck when it was gutted by fire in 1994, but thanks to Daimler Benz it was rebuilt and restored. Scheduled to be opened to the public, it was again the target of arsonists and finally opened on May 17, 1997 under the aegis of the Atlanta History Center who now maintain it as a centre for literature and the arts.

Describing the book as a ‘timeless classic’, Hillary Hardwick, Vice President of Marketing Communications of the Atlanta History Center says the House focuses on Mitchell as a writer and the legacy she left, with regular programmes being organised with visiting authors. “There are many collections of Mitchell around Atlanta,” Hardwick says, “but this is the birthplace of Gone with the Wind.”

What the visitor discovers in that brief tour through this little apartment from the framed writings and family photographs on the wall are the many parallels between Mitchell’s life and the underlying threads of the book. Born to a prominent Atlanta family, her father a lawyer, her mother a suffragette she was given to writing and acting from a young age. Writing in her journal on January 7, 1915, the young Margaret aged 15, made her intentions clear, “I want to be famous in some way -- a speaker, artist, writer, soldier, fighter, stateswoman, or anything nearly.”

|

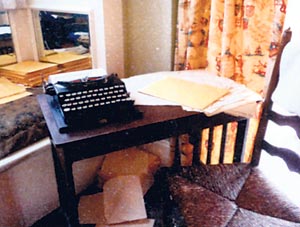

| As it was: Her writing corner |

That passion to write led her to become a reporter in the Atlanta Journal in an era when newsrooms were largely a male preserve, writing under the name of Peggy Mitchell. Making her debut in society in 1920, she scandalised the conservative matrons of Atlanta by doing the Apache, a provocative dance of the Jazz Age with a friend, much like Scarlett in the book defies convention and her widow’s weeds by taking the floor with Rhett at a charity bazaar. Like Scarlett whose mother Ellen dies before she can get home from the siege of Atlanta, she did not make it to her mother May Belle Mitchell’s deathbed, being away at Smith College in Northampton.

Margaret married twice. Her first marriage to the eccentric Red Upshaw, credited by some to be in part the inspiration for the character of Rhett did not last long and one of the tidbits our guide ventures, is that her second husband John Marsh was part of that first bridal party, having been one of her suitors even then and Upshaw’s friend and room-mate. In Marsh, by all accounts she found a bulwark of support and understanding. By some strange coincidence, July 4, was the day Margaret Mitchell wed John Marsh after the latter suffered a strange illness and their Valentine Day nuptials had to be postponed.

By 1929 she had written most of the book but then moved on to other things, her ankle now healed. “I vaguely recall that I just sat down and began to write a book to occupy my time. And after I finished it and was able to walk again, I put the book away and forgot about it for years,” she was to remark later.

It was all of six years later when a publisher from Macmillan - Harold Latham came to scout for new talent that it resurfaced, that too quite by chance. Margaret was showing Latham around Atlanta when he asked if she had ever written a book. The story goes that she twice denied having written a novel when directly questioned by him but when a friend injured her pride with the remark ‘Imagine anyone as silly as Peggy writing a book’ she pulled out the envelopes and delivered them to Latham just as he was ready to leave with the words, “Take this before I change my mind’. So unwieldy was the lot that Latham had to buy an extra suitcase to carry it.

Back home, Margaret rued her impetuosity and sent Latham a telegram ‘Have changed my mind. Send manuscript back’. It was too late. Latham knew he was onto a winner. He encouraged her to complete the book and had Macmillan send her an advance cheque.

Interestingly, the last chapter had been written first and the rest were composed in no particular order. The book was published in June 1936 but not before Margaret had made some significant changes. She wrote in the first chapter and equally important, finally settled on a name for her heroine. Thus Pansy O’Hara became Scarlett, Fontenoy Hall became Tara and the title of the book ‘Gone with the Wind’ from one of her favourite lines of poetry by Ernest Dowson’s - dismissing ‘Tote the Weary Load’ and ‘Tomorrow Is Another Day’, some of her earlier options.

The book was a runaway bestseller, going on to win the Pulitzer Prize.

Fame overtook her life and overwhelmed her, though she remained ambivalent about her work. Hillary Hardwick emphasizes how much she gave back to Atlanta, citing her volunteer work with the Red Cross and how she started a literary contest for prisoners at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary. Though hating the attention that now dogged her steps, she stepped forward to champion causes close to her heart like the war effort, sponsoring the US navy cruiser Atlanta (it was sunk just a year later and replaced) and unknown to most, donating scholarships for black African-American medical students at Morehouse College, Atlanta.

We leave the book to cross the street to the museum for the film where there is enough movie memorabilia for ardent film buffs to revel in, from the stunning portrait of Vivien Leigh as Scarlett ravishing in her blue satin dress that hung in the Butler home to costume sketches, set pictures and more. The film was every bit as successful as the book winning ten Oscars including best picture, best director, best actress and best supporting actress, the first Academy award to be won by an African American, in this case Hattie McDaniel who played Mammy, Scarlett’s devoted housemaid. Yet when the film had its glittering premiere in Atlanta with all the celebrities in attendance – Vivien Leigh, Clark Gable and David Selznick side by side with Margaret, the South’s strict rules of segregation still apparent made it impossible for Hattie to attend.

Selznick’s film remains a classic. “For millions around the world the movie Gone with the Wind defined the South for much of the twentieth century. Images from the film, not the book have fostered stereotypes that have shaped public expectation about the people and the landscape of the South particularly Atlanta,” states one panel in the movie exhibition.

Margaret Mitchell and John Marsh had left ‘the Dump’ in 1932 to move to the more spacious Russell apartments not far away. But on August 11, 1948 Margaret was run down by a cab as she crossed Peachtree Street on the way to the theatre. She died in hospital five days later. She was 47.

She had remained resolute that she would never write a sequel to Gone with the Wind, resisting enormous pressure to do so. “She was a woman ahead of her time,” our guide said reverently. And an enigma, it seems, to this day.

|