| The sprawling old, the exciting new Living in Sri Lanka by James Fennell & Turtle Bunbury. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0–500–51287-6. For sometime I have been inspired by Thames & Hudson, one of the world’s greatest publishers of illustrated books. This is especially so as in 1971, two years before my first landfall in Sri Lanka, there appeared an exceptional work on the country by them that caught my attention in a London bookshop. It is one of a handful of English language books – the first being Robert Knox’s An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon (1682) - that will no doubt continue to be considered by generations of readers as essential to an understanding of the country.

With magnificent photography and design by Roloff Beny, and a thoughtful edited anthology of the historical writings on the island by Lindsay Opie, the book in question, Island Ceylon, is presented in breathtaking fashion. It is a sumptuous slab – literally - printed on thick, tactile paper. Nowadays it is so rare and precious to bibliophiles, especially the often suspicious Sri Lankan variety, that it is unlikely to be chanced on a coffee table. But then, ironically, English rodents ate a chunk of my copy’s cover during a period of storage. Now thirty-six years later appears another book on Sri Lanka by Thames & Hudson; an illustrated selection of wondrous homes with a sprinkling of guesthouses and hotels called Living in Sri Lanka, created by James Fennell and Turtle Bunbury. Fennell is the photographer and Bunbury the writer. Both have impressive family connections with the island. Fennell’s great uncle, Colonel Thomas Wright, was the only suddha to sit in the first senate after Independence, while Bunbury’s great-grandfather was ADC to the Governor-General before the First World War. In 1912 he married the daughter of Bob Ievers, a well-known civil servant who possibly arrived in Ceylon as part of Sir William Gregory’s administration and was certainly a friend of archaeologist H. C. P. Bell.

It is hard not to compare the two books, products as they are of such a thoroughbred stable. Being from a different age, Living in Sri Lanka does not have the appearance of Island Ceylon. It lacks distinction in many ways: the colour combination of the jacket spine is unfortunate for instance. More important is that the text does not have the polished accuracy of Island Ceylon. If you are accustomed to reading the jacket blurb before commencing a book I suggest with Living in Sri Lanka you give it a miss. This is because the very first paragraph reads: “The ancients called it the Island of Serendipity. Since 1972, it has been Sri Lanka, the ‘auspicious’ (Sri) island to which King Lanka eloped with Rama’s beautiful wife in the 2000-year-old Hindu epic.” The “ancients” seem to have risen the historical ladder, for serendipity (how such a marvellous word has become so abused) was not coined until 28 January 1754. “King Lanka” is yet another piece of nonsense: King Ravana is the name of course. And, incidentally, why isn’t the Ramayana named for the information of readers instead of being described as “the 2000-year-old Hindu epic”? (Anyway, shouldn’t it be “a 2000-year-old Hindu epic”?) One can forgive Bunbury the lapses of the publisher, but at the start of his introduction, in providing a sketch of the island and its history, he gives the impression that King Solomon came to the island to procure the ruby that won him the heart of the Queen of Sheba, when in fact he sent emissaries. Bunbury also has a problem with the spelling of Mahaweli in the introduction. I found later many such errors throughout the book, some of which we will encounter along the way. On this subject, the British reviewer Andrew Robinson has recently drawn attention to the blemishes caused by the misspelling of Sri Lankan place names in Victoria Glendinning’s biography of Leonard Woolf.

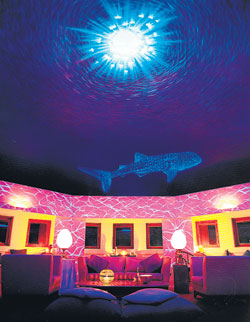

When Bunbury shifts his attention to the story of Sri Lanka’s architecture, however, his writing becomes more assured. It being a wet tropical island, he notes the importance water has as a backdrop for dwellings. He then waxes lyrical in listing some relevant examples – examples that provide a fair indication of the varied content of the book: “Along the south-west coast, villas sprawl between wind-blown coconut groves and the Indian Ocean. North of the pilgrim city of Kataragama, a wandering gem merchant has built a hamlet of thatched huts along the banks of the Manik Ganga, the fabled River of Gems. On the west coast at Balapitiya, a restored cinnamon planter’s villa rolls down to the estuarine waters of the Madhu Ganga. In the jungles east of Colombo, tree houses overlook the mighty Kelani. North again at Ulpotha, a two-thousand-year-old reservoir provides the backdrop for a sumptuous 21st-century eco-village.” Some of the properties featured in the book are owned by locals, but many are owned by foreigners (there is now a 100% transfer tax for foreigners). In revealing the provenance of the properties, Bunbury writes first of those that are restored older buildings, victims of Sri Lanka’s “impoverished status” during the late 20th-century. Then there are the contemporary additions, “most notably along the Serendib Riviera” (Sri Lankans, especially homeless tsunami victims, please note: this is simply the south-west coast). These new buildings have been designed by both Asian architects such as Sri Lanka’s late lamented Geoffrey Bawa and his “spiritual heir” Channa Daswatte, as well as others such as the Australian Bruce Fell-Smith. The fact is that whether it was restoration or construction, much of the work on the buildings has occurred only in the past decade. Bunbury also notes that “a new wave of interior designers, furniture-makers and artists has arisen”, combining locals such as Shanth Fernando and Nayantara Fonseka along with foreign residents such as Nikki Harrison and Saskia Pringers, that heralds an “exciting new dawn for Sri Lankan art and design”. Living in Sri Lanka is divided into three sections. The first, “Town & City”, covers ten houses in Colombo and Galle. (According to an observer other than Bunbury there is a “300-strong foreign – and vaguely aristocratic – community” in Galle.) Bunbury provides a comprehensive history of each house and informative captions regarding the architectural elements and decorative works of art captured in Fennel’s photographs. These private dwellings range from Mary McIntyre’s Doornberg, possibly the most elegant and certainly the oldest villa in Galle, to Giles Scott’s fluorescent fantasy, The Dome, at the Galle Face Court in Colombo. In contrast is the little known The Last House at Mahawella, owned by Tim and Sarah Jacobsen, which was Bawa’s final private house design, completed with the aid of Channa Daswatte in 2001. Bunbury (who finds the spelling of Kandalama difficult in this instance) claims that The Last House is “indeed one of Bawa’s greatest works”. “Jungle and Hill Country”, the third and final section, is possibly the most interesting, containing as it does some extraordinary architectural and decorative ideas located in some of the most breathtaking areas of the island, away from the seaside milieu. The 1930s Kandy guesthouse rightly named Helga’s Folly – the Helga in question being owner Helga de Silva Perera Blow - is a case in point. Described as “one of the most outrageous guesthouses in the world”, the chaotic, overblown art deco interior captured by Fennell is in stark contrast to the often prim interiors of the book’s other examples. Another unusual property is Ulpotha, Bunbury’s “sumptuous 21st-century eco-village”, centred on a 1990s restored walauwa next to a tank. (But oh dear! Having spelt it correctly earlier, Bunbury now makes a mistake with Kataragama.) Owner Viren Perera added an ambalama where guests take meals, built mud huts for accommodation, set up an organic farm, and declared Ulpotha a paranagama, thereby involving the local farming community. However, the book’s most outstanding featured property as far as I am concerned is Rukman de Fonseka’s Galapita - “one of the most exciting new additions to Sri Lanka’s burgeoning eco-tourism industry” - located close to the Manik Ganga. From the moment guests arrive and find the cottage that provides entry is comprised of merely one wall they know they are in for something very different. Although much like Ulpotha in its sense of tradition and simplicity, Galapita has the edge with its superb location. In the final analysis Living in Sri Lanka succeeds in portraying this new architectural rush in some style. Despite his hiccups with local spelling, Bunbury has written an agreeable text, complimented by Fennel’s simple and unobtrusive photography. It may not stand out on the bookshelf like Island Ceylon, but it deserves to be there nevertheless. |

|| Front

Page | News | Editorial | Columns | Sports | Plus | Financial

Times | International | Mirror | TV

Times | Funday

Times | Kandy Times || |

| |

Copyright

2006 Wijeya

Newspapers Ltd.Colombo. Sri Lanka. |