17th September 2000

News/Comment|

Editorial/Opinion| Business| Sports|

Sports Plus| Mirror Magazine

- Wild Show

- Inspired by imagination he creates a world of beauty

- Dancesport time again

- Upon my mother - A Taste of Sinhala

- Vanishing beauty

- Writers, awards and a launch

- Why do we teach and what do we teach?

- Fleeting brushes with the famous

- Strong and gentle ode to horrible times

- Missing story

- Moving testament of life and divinity

- Sagacious Senanayakes of Sri Lankan politics

- Law and Citizen - Law and Citizen

- Go Duncan, go,go

- Pearlfect!

- Paper magic

- JR, a man with humour

- A royal magazine

- Ladies' night of This and That

- Tommiya's back and he's educating himself!

- Letters to the editor

Wild Show

Caught up in a world of commercialism, a once proud people, the

Veddhas have virtually turned into mere exhibits selling their culture

to both local and foreign tourists.Kumudini Hettiarachci reports

Kota Bakinaya, off Dambana: Adapt and survive or face extinction, has been the difficult choice before them. And they have decided to adapt and survive by practically giving up their hunter-gatherer way of life and selling their "culture" to both local and foreign tourists. This has been the fate of the country's Veddhas who boast of ancestors going back to many, many centuries before Vijaya landed in Sri Lanka.

Going along the Mahiyangana-Batticaloa Road, as you turn left at Dambana, you come upon Veddha country. You don't know whether to be sad or happy when you see the Veddhas on show along the road.

In this part of the country it's big business for at Dambana itself children stop you and ask you whether you are looking for the Veddhas and if so, they would act as guides and interpreters. Then one child hops into the vehicle and you are on your way to see the Veddhas.

As you near Kota Bakinaya you see the Veddha colony the child eagerly points out one Veddha and says he would dance for you to take some photographs. Along the way is also a tiny cadjan tea boutique, which proudly announces that it has Dambane Gunewardene's books for sale. You pass the village school, which has a hall named after Tissahamy. Then the rutted road forms a natural bend and there is parking space with massive trees, most probably as ancient as the Veddha civilization.

The day we went to Kota Bakinaya, there were 12 big buses and coaches parked here, with people going in procession to see the Veddhas.

The moment you park, more small boys offering to look after the vehicle surround it. They are the children of the Veddhas or from Veddhi-Sinhala mixed parents. At the head of the pathway leading to the Veddha cottages, two or three bare-bodied Veddhas sell their wares of tiny ivory baubles and knick-knacks.

They are ever willing to pose for photographs, with their axes slung over their shoulders and carrying their bows and arrows, for a small fee.

From

there it's on to the home of Uruwarige Wanni Aththo considered the chief

of the tribe to see him and also view the photographs put up on the mud

walls of his humble abode of him at the UN and various capitals of the

world.

From

there it's on to the home of Uruwarige Wanni Aththo considered the chief

of the tribe to see him and also view the photographs put up on the mud

walls of his humble abode of him at the UN and various capitals of the

world.

The

next stop is the 'museum' with Tissahamy's worldly possessions, including

the hearing aid he wore later in life and photographs. There sits Kadira

whose eye had been gouged out by a bear who is Tissahamy's son by the

first marriage, ready to have a chat.

The

next stop is the 'museum' with Tissahamy's worldly possessions, including

the hearing aid he wore later in life and photographs. There sits Kadira

whose eye had been gouged out by a bear who is Tissahamy's son by the

first marriage, ready to have a chat.

The tour ends at that point. One thing that struck us was that though the Veddha women were seen doing their daily chores, when we attempted to talk to them, they quickly moved into their homes and shut the door. Our small interpreter explained that the women never spoke to strangers, even other women, if their men were not in the house.

"Money has been the cause of all our problems and our downfall. We have had to depend on money since the government made this a protected area and hindered our normal lifestyle of hunting," Uruwarige Wanniyala Aththo, son of Tissahamy from his second marriage, said. Seated on a mat in the verandah of his hut, along with Dambane Gunawardene, while visitors gaped at us in curiosity, I had a two-hour chat with the tough and eloquent Uruwarige (54). Though after a time, I could understand what he was saying, as the language is different, now Dambane Gunawardene was acting as interpreter. Explaining that they can no longer hunt in the jungles they considered their home, Uruwarige hastens to add that they had their own rules with regard to hunting. "There was no indiscriminate hunting. We didn't kill young animals, or pregnant females. We didn't kill animals, which were drinking water. We also didn't waste any meat. Generally we hunted only wild boar (pig), deer and sambhur." What is their routine? I ask and he laughs gently, for they don't have a regimented, daily routine like we do. No clock governs them. They wake up whenever they feel like it; go hunting whenever they are hungry; grow a few crops such as Indian corn and maize, whenever the rains come and if they need things like salt, they would barter some honey or a piece of meat. They also sleep whenever they feel like it. But all that has changed for around 5,000 Veddha families in this country. Previously they never thought of tomorrow, but lived for the day, but with money coming into the picture, life has changed. "Our culture was such that we never saved for the future. That mindset is still persisting, but with money you can't be like that. Most of the Veddhas are in debt, because we don't put something aside for a rainy day.

"Now we do odd-jobs or a little bit of chena cultivation. We also collect honey from the jungle and sell it to the boutique close by. Those days we led a self-sufficient life," Uruwarige says.

"Our main backdrop was the jungle. We resorted to chena (slash-and-burn) cultivation. But now we don't have that freedom to go anywhere and find our own food," he says.

Can you blame the Veddhas for earning money this way? he asks me when I query about commercialization.

"Those days we didn't have proper houses. We lived wherever we went to hunt in the jungle. We also didn't fall ill, because we ate what we gathered. Whatever minor illnesses we got we treated ourselves with herbs and other plants found in the jungle itself. Hospitals, doctors and medicine in the form of tablets and coloured water were alien to us. Our women had their children at home. But now we are dependent on money for our survival."

With that have also come other problems of serious illness and malnutrition. Many are suffering from diabetes, high-blood pressure and chest pain. It seems as if the environment has turned toxic.

These things were not there when they were dependent on the jungle for their daily needs, he says, adding laughingly that now they had to get modern things such as spectacles (a pair of which was with him) to overcome these drawbacks.

Those days there was also no signing after a marriage. If two people liked each other, they lived together and had children and fended for each other. No man would take another woman as long as his first woman was alive. But, if she died, then he could take another. If in case a couple found that they could not live together, the man would hand back the woman to her parents in an honourable manner.

"Our belief is that we belong to the Yaksha tribe. We are born of this earth and are indebted to it. That's why we don't cremate, we bury, so that we can at least give back our bodies to the earth in return."

Uruwarige says his globetrotting days began after the UN declared the International Year of Indigenous People. He has met many tribal people such as his own and travelled to many a capital, even climbing the Alps.

As I bid goodbye in the traditional Veddha way of touching his palms with my own, he says his only wish for his people is that they would be allowed to roam this land, hunting and gathering like their ancestors. "We don't want to own even a tiny plot of land. We just want to be free," he adds.

'Money the root of all our problems'

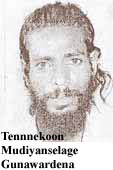

The

only graduate among the Veddhas, Tennekoon Mudiyanselage Gunawardene (32),

is looked upon with respect by the others. For not only has he been to

university in Colombo, he has also written two books, one of which was

released on August 9. They are "Dadabimen Dadabimeta" (From Hunting Ground

to Hunting Ground) and "Veddhi Gee Vimasuma".

The

only graduate among the Veddhas, Tennekoon Mudiyanselage Gunawardene (32),

is looked upon with respect by the others. For not only has he been to

university in Colombo, he has also written two books, one of which was

released on August 9. They are "Dadabimen Dadabimeta" (From Hunting Ground

to Hunting Ground) and "Veddhi Gee Vimasuma".

A grandchild of Tissahamy through some distant relationship, Gunawardene, according to the Veddhas is "mixed". His father is a Sinhalese and his mother from the Veddha community. Now he is a teacher in the most remote school in that area.

Yes, he has seen or recorded after research, a transformation in the lifestyle of the Veddhas in the past 25 years. The deterioration began when they had to deal in money. "There was a social change, but the community was not mentally equipped to face this," he explains. Earlier, only a few foreigners came looking for the Veddhas after reading the well-documented books of R.L. Spittel. Commercialization began in earnest, in the early 1980s, with government moves to resettle the Veddhas. Then the locals came in their busloads.

He sees a vast change from the lifestyle his mother used to describe and now. That's why he decided to write about this crucial issue, otherwise the younger generations would never know how they hunted, cultivated, ate and lived a very quiet life. Their language and poetry would also be lost to posterity that's why the second book came along.

He too sees money as the root of all their problems, but is philosophical about it. "At least they are not killing or hurting anybody, to earn a livelihood. They are only earning a few rupees by selling small handicrafts, bee's honey, dancing for a crowd or being photographed," he says.

![]()

Front Page| News/Comment| Editorial/Opinion| Plus| Business| Sports| Sports Plus| Mirror Magazine

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to