2nd July 2000

News/Comment|

Editorial/Opinion| Business| Sports|

Sports Plus| Mirror Magazine

- Winds of change across Maskeliya

- What's culture: all that man has created — the good and bad - Kala Corner - by Dee Cee

- One man's mouth is another's tongue - A Taste of Sinhala (24)

- Percussion: a source for expression and communication of mankind

- Something Old, Something New

- Meaningful journals for Sri Lankan cinema - Book Review

- World trade: challenges facing Sri Lanka

- The Vanquisher of 'Tygers'

- That clubhouse ambience... - Travel

- They did it in style

- News 100 years ago

- "Buddhism in Europe"

- Her life has been so fulfilling - Down Memory Lane

- His was a life of dedication, fulfilment and achievement

- Mining, washing and polluting - A view from the hills

- Kandy's new Kalabooshana

- Winnie's first impressions of France

- Village culture, eco-tourism and hype

- Terrorists, rebels and life's ironies - Thoughts from Londond

- A change of heart and a new beginning

- The 'art' of heart

- Peoples and Events

- Psychotherapy counselling: an urgent need

- Letters to the editor

Winds of change across Maskeliya

New management methods at tea estates improve productivity and working conditions

By Feizal Samath

A receptionist at a Sri Lankan tea factory? I was amazed the other day to walk into a small but comfortable reception area at the Strathspey estate tea factory in Maskeliya and be greeted by a smiling Sangaran

Jeyarani, neatly dressed in a saree. The 24-year-old GCE O/L qualified

Jeyarani is the daughter of a tea-plucking couple working on the estate.

Sangaran

Jeyarani, neatly dressed in a saree. The 24-year-old GCE O/L qualified

Jeyarani is the daughter of a tea-plucking couple working on the estate.

"I enjoy this work," she says, wiping the neat front desk and arranging a vase with fresh garden flowers. She greets visitors to the factory, maintains a time-record for factory staff and answers the telephone.

"It was all his idea," says Fred Amarasinghe, operations director of Maskeliya Plantations Ltd, pointing to estate superintendent Ratnasiri Ranatunga. "He believes that if you spruce the place up and make the factory environment comfortable for workers — executives and minor staff — then productivity will improve and people will have fewer complaints to make."

Audio speakers are fitted across the factory premises with preferred Tamil music meant to soothe workers. Comfortable beds and linen, changing lockers, hot and cold water showers and a television set in a sitting room area are provided in a separate building for those who work the overnight or "graveyard" shift.

"We treat the workers as human beings, not a number on a roster or an

unknown figure carrying a  basket

on the tea field," says Mr. Ranatunga.

basket

on the tea field," says Mr. Ranatunga.

The life of the estate worker — written about for many decades as one of being downtrodden, ridiculed, beaten and treated often worse than chattel during the time of the British Raj — may have not changed dramatically in recent times after plantations came under private sector management and ownership. But things are moving quite fast and the transition is remarkable though trade unions and women rights activists continue to be critical of worker conditions — neglected housing, illiteracy and poor health services.

Strathspey and other plantations companies are infusing new capital for human development and new technology much faster than it would ever have happened during the era of nationalised plantations.

Most critics would concede that the standard of life of the plantation worker has improved in the past decade and they are better off than rural farmers and workers.

Farm incomes have been stripped to the bone in recent years due to higher costs of production and rising cost of living. Farmer-families are more dependent on remittances from family members working in West Asia, in the army and nearby garment factories though critics would argue that plantation workers do not have the same freedom or political rights like everyone else, due to long delays in getting a Sri Lankan national identity card and voting rights.

Yet plantations have come a long way from the 1960s and even the 1970s when female tea pluckers got up at the crack of dawn to prepare breakfast, tuck a dirty cloth round their body and walk to the fields where they were greeted with choice words by senior and junior field officers.

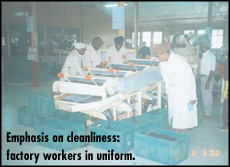

"The use of slang or derogatory words is history on the plantations. Workers are treated with more respect now. We treat them in a dignified manner, call them by their names and give factory workers neat uniforms," Mr. Ranatunga said. Tea pluckers are better dressed now, given raincoats and boots by the Maskeliya management to protect them from rain and leeches. They are also provided with hot, steaming tea on the fields by the company during breaks. Earlier they were compelled to bring their own tea, made at dawn, which is cold by the time they drank it. "Chasing" was a common practice those days. If a worker failed to turn up on time for early morning "muster" or roll call, he or she was chased away with a few "choice" words by the field supervisor. Not anymore. "Plantations have developed more decent ways to tackle this issue," said Mr. Amarasinghe, noting that the early morning muster call in the biting cold would also probably fade away.

In April this year, three factories owned by Maskeliya Plantations, a subsidiary of the John Keells group, were awarded the ISO 9002 standards certification by the Sri Lanka Standards Institute. It was the first time in Sri Lanka that a tea factory had achieved this standard.

Maskeliya Plantations has also put in place the Japanese 5-S concept, which according to Mr. Ranatunga is a process where "there is a place for everything and everything is in place."

This is not the only tea factory to run according to Japanese management concepts, the first being the Great Western tea factory in the Talawakelle area. "We must give credit to Great Western for starting this concept in tea factories," said Mr. Amarasinghe, noting however that Maskeliya Plantations had developed more innovations since then.

The famed Japanese 5-S management is being followed by many Sri Lankan companies and local executives receive scholarships by Japanese-funded agencies to study the system in Japan.

Mr. Ranatunga, who visited Japan under one of these programmes, said an organised workforce, discipline, cleanliness and a pleasing environment to work in were the fundamentals of the 5-S concept. It improves productivity and the lifestyles of the workers, he said. Indeed, factory floors are tiled and clean. Trolleys are used to carry the tea from one point to the other if not sent through newly installed conveyor belts. Walking paths are clearly demarcated in black and white. Spillage is at a minimum and quickly swept away.

Earlier 80 percent of the tea spilled on to often-dirty cement floors. Workers have been told to treat tea with care as it is consumed by someone in some part of the world.

"Our factories are moving towards the food factory concept where hygiene and cleanliness play a vital role at all levels of production," said Mr. Amarasinghe, removing his shoes and putting on a pair of boots, a white overall and a cap as part of strict hygienic measures. All visitors must do a similar change before entering the factory.

Factory walls are pleasing to the eye with colourful pictures — many drawn or painted by workers — explaining fire escapes, security, exit doors and other instructions. Factory tools are neatly placed in specially demarcated areas under an "easy to find" rule. Workers move around in uniforms and caps provided by the management. Worker-management relationships have improved tremendously from the fiercely confrontational days of the 1970s, 1980s and early 1990s. All workers are provided with free medical care. They have personnel files where medical details and other data are maintained. "The most interesting thing is that workers, having realised that management is changing and accommodating unlike before, have invested their own money for uniforms and other facilities. They even partly contributed to the Hi-fi music system and television set.

Out of two uniforms a worker gets, one is fully paid for by the worker," Mr. Ranatunga said.

This is the process of participatory management. "We work as a team — management and the workers — not as separate entities. Workers are consulted on new developments, new techniques and often their views taken into account. There are constant brainstorming sessions between worker representatives and management on various issues," he said.

Annual trips are organised for the families of the 12 best tea pluckers. Last year the group was taken to the Dehiwela zoo and the Galle Face Green for a — believe it or not — first time glimpse of the sea. Most plantation workers have never stepped out of their estates. The management holds an annual year-end party where they sing and dance till the wee hours of the morning.

The workforce is also more educated and intelligent than before. Most of the factory girls have either passed their GCE O/L or studied upto acceptable standards. Three estate youths who have succeeded in gaining entry into universities receive 1,000 rupees, each, every month from the Maskeliya management as a financial grant.

Like other plantations, Maskeliya also has an estate crèche manned by competent staff for the children of workers. Pregnant mothers are given work in nearby fields to reduce their walk-time. A savings scheme is in place organised by the area's Bank of Ceylon branch while the management has provided 8,000 safety lamps — replacing the traditional but dangerous lamps made out of old bulbs — to all homes.

The other two factories to obtain ISO 9002 standards — Brunswick and Laxapana — have similar measures, tiled and clean floors, airy rooms and upgrading of machinery. The nearby Glenagle tea factory also owned by Maskeliya Plantations looks drab, dreary and cold. The floors are dirty and tea is stacked on the ground in huge mounds. There is dust all over. The worker's rest room is like a cattleshed.

"Don't worry," assures Mr. Amarasinghe. "The three factories that you visited were similar or even worse in appearance and standards before the ISO and 5-S transition took place. Eventually all our factories including Glenagie would be developed into hygienic food factories like Strathspey," he said.

The Maskeliya factories have also won several quality awards over the years.

![]()

Front Page| News/Comment| Editorial/Opinion| Plus| Business| Sports| Sports Plus| Mirror Magazine

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to