|

17th January 1999 |

News/Comment| Editorial/Opinion| Business| Sports | Mirror Magazine |

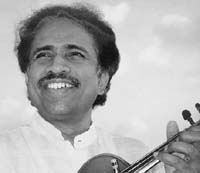

Seeing a universality in any musicConcert ReviewBy Madhubhashini Ratnayake Last

week Sri Lankan audiences had a chance to witness a famous international

artiste in performance, when Dr. L. Subramaniam played at the packed BMICH

on Monday and an equally overflowing hall at the Indian Cultural Centre

the next day. Last

week Sri Lankan audiences had a chance to witness a famous international

artiste in performance, when Dr. L. Subramaniam played at the packed BMICH

on Monday and an equally overflowing hall at the Indian Cultural Centre

the next day.

Dr. Subramaniam is a violinist from the Karnatic music system of India who also holds an MA in western music. It is not often that you see the same musician sitting down to perform the violin with its neck resting on his foot in the first half of the concert, and see him carry it under his chin in the next. But that, however, was what Dr. Subramaniam did, being trained in both, and crossing over from one system to the other so easily that unless you thought about it, you would not realize that he was dealing with two traditions of music. He was accompanied by other musicians from the East and the West. It was a heartening sight to see the 1,500 seats of the BMICH almost full on Monday (11) and realize that in Sri Lanka it is not only the stadiums that get packed. The concert went on till about 11.p.m. and everyone was still there to give the musician a standing ovation at the end. The first half of the concert was dedicated to pure Karnatic music, when he played 'Vatapi Ganapati' by Muttuswami Dikshita, in Raga Hamsa-dhvani. Personally, I found this the most brilliant part of the concert, since there seemed to have been no restrictions to letting his imagination and creativity roam free in the act of improvisation, which is the cornerstone of Indian classical music. There is a limitation of this spirit, a holding back, as it were, of the need to soar in utmost freedom in musical fantasy when it comes to playing with other musicians, since composition necessarily implies the limitation of such individual freedom. The alapana on the violin at the very start of the raga held the quietness and reverence of his spirit and the haunting beauty of Raga Hamsadhvani and one wished that it could have gone on a bit longer before the fiery brilliance of the percussionists and the ecstatic exchanges between them and the violin look everyone's breath away. The highly charged atmosphere between the mridangam, ghatam, tavil, and morsing, with the main performer was clearly apparent, and the rapt attention of the audience was enough to make them part of the whole experience of 'living' music. The second half saw the appearance of musicians from other lands and other traditions. Subramaniam sees in music, a universality and emotional depth which transcends all barriers; but he also acknowledges that within countries, there are differences and different styles of playing, which is also valid and important. "If you play an open string of a violin, for example," he said, when he met the press the following day, "it is impossible to say in what tradition the musician has been trained in. It is pure music. "The sound of the note. But if one were to play notes on that string, then one would know immediately, due to the various styles of playing, the various ornamentals etc., that he would have learnt under the Karnatic tradition, the Western classical tradition etc." So, it was interesting to note at this concert, examples of other 'unmixed' music from the West (though it would be difficult to limit the cardboard box so ably played by the young Thomas Menzir as belonging only to the West!) when Kim Menzir on an assortment of wind instruments and Tom Nielson on classical guitar gave us examples of the music of the Scandinavian area. There was also the aboriginal Australian 'Diggiriroo' - a long wooden tube and nothing else - played by Kim which left us in awe, more than anything, of his breathing prowess. He had, he admitted later, learnt the art of continuous breathing, and could keep playing a wind instrument without a break in the sound production. As instruments such as this and the bamboo flute which he played, were unfamiliar instruments to us in Sri Lanka, Dr. Subramaniam's comment - that to take musicians from all over the world to tour other countries together makes sense since most people cannot afford to travel abroad and see the various traditions of music themselves - seemed valid. The four percussionists forming the 'Madras Ensemble', K. Sekar on tavil; K Gopinath on mridangam; E.M. Subramaniam on ghatam and Ghantasala Sathya Sai on morsing had a moment to themselves when they came on the stage to play a tala vadya. The final three pieces of the concert were three compositions by Dr. Subramaniam - Tribute to Departed Souls, Apna Street and Ganga. Sanjay Wandrekar on keyboards and Dominic Fernandez on bass guitar joined in and Dr. Subramaniam's young daughter, Seeta, also lent her voice to one piece. It is a pleasure to see them both on the same stage. The music was beautiful and we hope that one day, Seeta Subramaniam would be able to match her father's playing with the power of her voice. The next evening, at the Indian Cultural Centre (ICC), where everyone was welcome to have a chance of meeting and talking to Dr. Subramaniam, there was the additional joy of seeing his two little sons accompanying him on the violin. The youngest, perhaps about five years old, played with such enthusiasm and seriousness in his twinkling eyes, that one would hope there is another great musician in the making. Dr. Subramaniam is here as part of the Independence Golden Jubilee celebrations of Sri Lanka. His visit to Sri Lanka is after about thirty years and is perhaps the most positive cultural event that happened in our country for a long time. Dr. Subramaniam's father and guru, Professor V. Lakshminarayana had come to Jaffna to teach music, and the child Subramaniam had spent his early days in Sri Lanka. His departure from the country, when he was still very young, due to ethnic violence, stands testimony to how much wealth we can lose due to intolerance and shortsightedness. Dr. Subramaniam has written symphonies, compositions which include jazz elements, and elements of various other music of the world. The divisions, if you take the base matter and the emotional content of music, he says, are false. That is why he tries to overlook the boundaries when he composes and produces music. "But before you try to use something in a style that is unfamiliar to you, it is your duty to study about it and learn it," he emphasizes. Before he attempted orchestration and Western techniques, he had got himself a Master's degree in Western music. Yet this kind of creative music poses no threat to Classical music, he feels. "Classical music has survived for years and years. We still listen to ragas. We still listen to Bach. There is no reason why that should be destroyed because new music is being made. I feel that for a musician to be in one place, not to try and make new kinds of music, is not quite right. But with that, he should also keep his traditional training and education." Dr. Subramaniam's instrument, the violin that he plays, is also an innovation, since it has six strings, one base string being added to the existing four. He uses another one which has sympathetic strings, or strings underneath the main strings of the violin, to vibrate according to the notes that are being played, thereby creating a fuller, richer sound. His violin has been amplified, so that there is no chance of it being drowned even if he plays with six percussionists, he says. Dr. Subramaniam has performed in most of the famous music auditoriums in the world. His performances in Sri Lanka have been done free of charge. Once he realized that the proceeds were to go towards the Integrated Theatre Workshop for disabled and non-disabled young people supported by the Sunethra Bandaranaike Trust, he had immediately volunteered to come here and play his music without payment. On Tuesday, despite his obvious tiredness, Dr. Subramaniam was willing to answer all the questions put to him by the audience at the ICC. After the performance, he was there till the end of the small party given by the ICC, talking to everyone who wanted to have a word with him. All this stands testimony to the fact that while being a great musician, he is also a good man. Indian music was born out of devotion and spirituality. We must be grateful for men such as Subramaniam for making us keep that in mind. |

||

|

More Plus * Vanya Mama a boon to students *Many many flowers from one Munasinghe

Front Page| News/Comment| Editorial/Opinion| Business| Sports | Mirror Magazine |

|

|

|

|