Sunday Times 2

Indian poaching in Lanka’s waters: Going round in circles for 5 decades

- The author Dr. Lanka Prasada, Ph.D. Commander (Rtd.) RSP, has personal experience in sea patrols in the northern waters as a Commanding Officer of five different ships of the Sri Lanka Navy. He has conducted extensive research on interagency collaboration and marine environment protection. He can be contacted by email lankacg@gmail.com

The media frequently report poaching by Indian trawlers in the waters of Sri Lanka and the fishing community protesting against the failure of the government authorities to prevent such intrusions.

The Palk Bay and Palk Strait areas in Sri Lankan waters are relatively shallow and rich with prawns. Sri Lanka loses an estimated Rs.5.3 billion each year due to poaching. This money could have lifted the standard of living of the Northern fishing community with potential fish exports and revenue in foreign exchange.

Northern fishermen protesting against Indian poaching in Lankan waters

Almost five decades ago, in June 1974, Sri Lanka and India jointly demarcated the International Maritime Boundary Line (IMBL) between the two countries. Still, the poaching by Indian fishermen is continuing in the northern waters of Sri Lanka. The law enforcement agencies are regularly making attempts to prevent it. India and Sri Lanka had several discussions but were not able to find a lasting solution. This article aims to provide a comprehensive view of maritime border protection in the Palk Bay and Palk Strait.

Historical Background of Demarcating the IMBL

The former Secretary of the Ministry of Defense and Foreign Affairs of Sri Lanka, Mr. W.T. Jayasinghe, in his book ‘Kachchativue: and the Maritime Boundary of Sri Lanka.’, mentions historical information on the demarcation of the IMBL. The first attempt to establish a maritime boundary between the two countries was made in 1920. The conference took place on 24 October 1921 in Colombo. The Principal Collector of Customs, Hon B. Horsburgh, former Government Agent of the Northern Province, led the delegation from Ceylon. During this conference, the point about ownership of Kachchativu Island surfaced. The Indian delegation proposed placing Kachchativu Island in Indian waters. The team from Ceylon maintained that Kachchativu Island belongs to Ceylon and not a matter for negotiations. Finally, the two teams reached an agreement to demarcate the boundary line three miles West of Kachchativu Island, placing Kachchativu Island well within Ceylon’s territorial waters. Though not ratified by either country, an agreement was reached on a boundary for fisheries purposes in October 1921 (Jayasinghe 2003, pp 13-15).

The next rounds of discussion took place in the 1960s and 1970s. The dispute about the ownership of Kachchativu Island had delayed agreement. The Indian team suggested that the Sri Lankan delegation make a ‘claim’ for the Kachchativu Island. Our team made its position clear that there was no question of Sri Lanka ‘claiming’ the Island, and if the Indian contingent believed that India had a ‘claim,’ they were free to do so. This incident shows the sharpness and alertness of the Sri Lankan officials of that era. Even a word that might impact Sri Lanka’s position was objected to and corrected to ensure that it did not weaken Sri Lanka’s stand.

The distance from the boundary line to Kachchativu Island was subject to intensive negotiations and the two Prime Ministers, Mrs. Sirimavo Bandaranaike and Mrs. Indira Gandhi, had to intervene to defuse the deadlock. Finally, both parties agreed to fix the boundary line one nautical mile West of Kachchativu. The formal bilateral Agreement was ratified on 8 July 1974 providing legal framework. Both countries approved another agreement on 10 May 1976, extending the maritime boundary of 1974 and demarcating the maritime border between Sri Lanka and India in the Gulf of Mannar and the Bay of Bengal.

Bilateral Agreements and the Truth in Interpretations

The main argument of the Indian stakeholders is that the Indian fishermen have the traditional right to fish in the waters of Sri Lanka under Article 6 which states that “The vessels of India and Sri Lanka will enjoy in each other’s waters such rights as they have traditionally enjoyed therein.” Similarly, Article 5 states that “Subject to the foregoing, Indian fishermen and pilgrims will enjoy access to visit Kachchativu as hitherto, and will not be required by Sri Lanka to obtain travel documents or visas for these purposes.” The Indian stakeholders interpret Article 6 as a right for Indian fishermen to fish in Sri Lankan waters. These Articles refer to the traditional navigation rights enjoyed by the Indian vessels. They should be considered together with Article 4, which states that each country has sovereignty and exclusive jurisdiction, and control over the waters and resources including subsoil on its side of the IMBL.

None of the Articles in the Agreement refers to fishing rights. If both countries had agreed on the rights of Indian fishermen, it would have included a clause in Articles 5 or 6 describing it. Then Foreign Minister Mr. Swaran Singh speaking in the Lok Sabha on 23 July 1974, clarified that the traditional rights mentioned were the rights of Indian fishermen and pilgrims to visit Kachchativu island and navigation rights exercised by Indian and Sri Lankan vessels in each other’s waters (Jayasinghe 2003, pp 100-101). This statement proves that traditional rights do not refer to fishing rights.

Mr. Kewal Singh, then Indian Foreign Secretary, wrote to Mr. W.T. Jayasinghe, Secretary of the Ministry of Defense and Foreign Affairs, on 23 March 1976, stating that “The fishing vessels and fishermen of India shall not engage in fishing in the historic waters, the territorial sea and exclusive economic zone of Sri Lanka.” In the same manner, Sri Lankan vessels shall not engage in fishing in the exclusive economic zone of India.

According to the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the agreements are considered as valid legislations in international law (UNCLOS 1982, s. 15). Article 21 provides provisions for the Coastal State to adopt rules and regulations related to innocent passage through the territorial sea for the conservation of living resources of the sea and the prevention of breach of the fisheries laws and regulations of the coastal State (UNCLOS 1982, s. 21)

Similarly, the Maritime Zones Act (1976, s 9), Sri Lanka exercises sovereignty, exclusive jurisdiction, and control over historic waters and islands, continental shelf, seabed, and subsoil within it. The terms sovereignty and exclusive jurisdiction of each country imply that they are applicable for all purposes. This documented evidence firmly establishes that Sri Lanka possesses the authority and powers of law enforcement concerning the domestic and international laws within its waters.

Reasons for Depleted Marine Resources in the Indian Waters of IMBL

The sea area between Sri Lanka and India has been rich with marine resources. The fishermen of both countries had been fishing in their respective regions, using traditional fishing methods. An Indo-Norwegian project commenced in the 1960s promoted the use of capital-intensive technology in fishing. The Indian government extended subsidies to encourage trawlers and the export of fish.

With continuous incentives for shifting from traditional fishing methods to trawling, more and more trawlers joined the fishing industry in Tamil Nadu that resulted in over-exploitation and fast depletion of marine resources in Indian waters. If this trend continues, we will face the same situation as India ended up with a lifeless marine environment in Palk Bay and Palk Strait.

There are 5,806 mechanized fishing boats in the State of Tamil Nadu, and most of them are engaged in trawling. The State Government is implementing the scheme on ‘Diversification of Trawl fishing in Palk Bay districts to deep-sea fishing’ with the Central and State Government’s financial assistance, without a time-based target (Government of Tamilnadu 2020, pp 50-52). They also have acknowledged in the same document that fishing by trawling is an unsustainable and unviable fishing practice. The continuous trawling operations have caused the depletion of its precious marine fishery resources (Government of Tamilnadu 2020, p 48). Yet, they hardly take decisive action to prevent the poaching by Indian trawlers which destroy and deplete the marine resources in the waters of Sri Lanka. The Foreign Secretary of India, Harsh Vardhan Shringla, requested Sri Lanka to consider Indian trawl-fishing in a humane manner (The Sunday Times 3/10/21). Meanwhile, India keeps a blind eye to the loss of livelihood of the traditional fishing community of Sri Lanka and the huge destruction caused to the marine environment by Indian fishermen.

Tamil Nadu declared a fishing ban for 61 days from 15 April as a fish-breeding period. They also proclaimed a small scale Fishing Zone of 3 nautical miles from the shore, for non-motorized fishing craft. Most fishermen in Tamil Nadu work for wages; about 75% of the boat-owners do not fish. They share a net income of 60% to boat-owners and 40% to the fishing crew. In some instances, it is only daily wages and incentives based on the weight of the catch (Utopia 2011). This system has led to the quantity-based targets of fish catches and incentives for illegal and destructive fishing in the waters of Sri Lanka.

The Indian trawlers in Tamil Nadu generally intrude into the Sri Lankan waters three days a week, excluding the 61 days fishing ban period every year. The Indian trawlers cross the IMBL in the evening and commence poaching with the nightfall, fill Sri Lankan waters by midnight and retreat to Indian waters in the early hours.

Sri Lankan patrolling vessel has to reach a poaching vessel of hearing distance to warn the crew. While the patrol vessel engages with one Indian trawler, dozens of other trawlers around the patrol craft cross the IMBL and enter Sri Lankan waters simultaneously; they scatter in the area quickly and start poaching. Once they are scattered, it is practically impossible for a patrol craft to approach each vessel. When a large number of Indian trawlers with dragging nets operate in the night there is the danger of getting the propellers of the vessel entangled with fishing nets. Only divers can clear the propeller. In most cases, SLN cannot match the intensity of intrusion to poaching.

The poaching pattern clearly shows that intrusions are intentional. The main concentration of poaching is in the area between Talaimannar, Kachchativu, and Delft Island. This area extending to 35 Nautical Miles is the most critical segment as it is the richest area for prawns. The next concentration of poaching occurs in the space between North of Delft Island and West of Karaitivu, which extends to 20 nautical miles. This scenario implies that these two segments should be given priority when formulating the maritime strategy of India and Sri Lanka.

Border Protection and Law Enforcement along IMBL

The Navies and Coast Guards of India and Sri Lanka independently carry out border patrols along IMBL in their respective waters. Yet, the statistics show that hundreds of Indian trawlers intrude and poach in Sri Lankan waters regularly. When Sri Lanka Navy (SLN) apprehends the Indian fishermen poaching, politicians blame SLN and organize protests in Tamil Nadu. Then the Indian officials impart pressure on Sri Lankan authorities. The apprehended Indian fishermen are either released without any legal action or by magistrate courts.

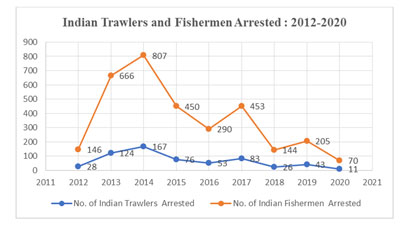

The following chart prepared based on an article published in Sunday Times on 19 September 2021 illustrates the statistics on Indian Trawlers and Fishermen arrested during the last nine years. Since Indian trawlers fish three days per week and 43 weeks per year, the total number of fishing days amounts to 129 per year. The Chart shows that the number of trawlers arrested per year varies from 11 to 167, resulting in an annual average of 68 trawlers. In other words, the daily average of arresting is below one trawler per day (0.52 trawlers). The Navy has capacity to arrest more than one trawler any day, and we need to ascertain the reasons for the decline.

Indian Approach and Political Ramification for Sri Lanka

Now, there is a shift in the stand taken by politicians in Tamil Nadu. Previously, they did not admit that Indian fishermen intrude into Sri Lankan waters and always made allegations of attacks by SLN. Now they refer to traditional fishing rights, humanely handling the issue, and allowing the Indian fishermen to fish in Sri Lanka’s waters. The central government of India sometimes bows down to the Tamil Nadu pressure. Recently an India-Sri Lanka Joint Working Group was formed to address the fishery issue. We observe that India neither intends to prevent poaching nor supports our stand on respecting the IMBL. They appear to be promoting a mechanism that would allow Indians to fish by granting rights to a certain distance in Sri Lankan waters, on specific dates. These proposals will lead to uncontrolled invasions by Indian trawlers and the ransacking of marine resources by the vastly outnumbered Indian fishing fleet. These would affect the territorial integrity and security of Sri Lanka with political and more complicated consequences involving two countries and fishing communities.

Economic, Social and Environmental Ramification for Sri Lanka

The fishing community in the Northern Province entirely depends on fishing in the Palk Bay and Palk Strait. The province has a fishing community of 216,040. Hence, the intrusion and poaching have become a socio-economic issue. The Fisheries Association of Northern Province has requested the government to confront invading Indian trawlers.

The bottom-trawling involves dragging the trawl net along the seabed and two heavy metal panels fixed at both sides of the mouth of the bottom-trawling net resembling a cow-catcher of a train. They pick and crush everything at the sea bottom. The damages caused to the marine environment include all the creatures at the sea bottom, plants, and corals.

Another critical issue our fishermen face is the extensive damages caused to their fishing nets by Indian trawlers in the mid-sea. Each net cost around Rs.400,000. The Sunday Times reported on 19 September 2021, occurrence of over two dozen such cases. This trend is dangerous as fishermen might end up taking the law into their own hands after losing faith in the law enforcement actions. It has potential to reach uncontrollable levels, creating massive security and political challenges.

The inadequate border protection consequences will extend to many areas such as movements of terrorists, criminals, illegal immigrants, weapons smuggling, explosives, narcotics, and human smuggling. The spread of the COVID-19 virus has added a new dimension concerning health safety. The Sri Lanka law enforcement agencies cannot proceed beyond the IMBL in the case of hot pursuit of any illegal activity. These facts illustrate why border protection is critical in Palk Bay and Palk Strait in the Sri Lankan context.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The matters discussed above have been continuing for five decades despite countless approaches and actions. It seems that we have been going around in circles without adopting an innovative strategy to address the issue.

The government of Sri Lanka is keen on transforming Sri Lanka into the maritime hub of Asia. In that case, the maritime strategy should fall in line with that vision. It should cover marine environment protection as well as border protection. Several stakeholders, such as public agencies and civilian bodies, are linked to border protection, law enforcement, and marine environment protection. An inter-agency collaborative mechanism involving all stakeholders is a must to address this issue.

We must abandon the piecemeal approach to focus on an all-inclusive strategy. This requires redefining and considering stakeholder perceptions with integrating several innovative approaches into a complete plan. The authorities could involve the experts in the field to discuss policies and processes at an appropriate forum.

It is for the government leaders at the highest level to decide whether to go around in circles in the next decade as well or not.