A reflection on what it means to remember

Anuk Arudpragasam: Writing, a key part of his life. Pic by Ruvin de Silva

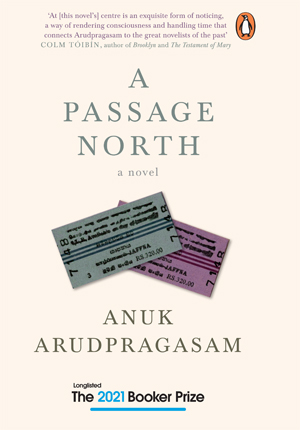

On the weekend I settle down to read Anuk Arudpragasam’s latest novel, recently longlisted for the 2021 Booker Prize, pictures of exhausted Public Health Inspectors and medical staff punctuate my social media feed. A news article announces that burial grounds in Ottamavadi – the sole site designated for the burial of the COVID-infected dead – is nearing its capacity. On one part of the internet, people are crowd sourcing oxygen and medicines for patients unable to access medical facilities. In another corner of social media, pictures of a perahera with over 5,000 participants are juxtaposed with a small memorialization in the North-East of the killing of over 50 schoolgirls, held amidst close military scrutiny. On a WhatsApp group, the news of a death emerges and after the initial condolences, the bereaved express relief that the funeral rites were able to be performed – there is a sharp realization that to engage in rituals of grief is a luxury during these times.

In many ways, Arudpragasam’s novel A Passage North feels like an elegy written through fiction. It reflects on what it means to remember, what it means to bear witness and to contend with the guilt of survival. Reading it is a reminder that for many Sri Lankans, long before the pandemic, the space to grieve, mourn and heal has always been a luxury.

A middle-class man living in Colombo with his grandmother and mother, Krishan is the novel’s restless, mentally peripatetic narrator. Physically, he is in Colombo and subsequently takes a train journey to the north to attend a funeral but his mind darts through time and place. This narrative restlessness is softened with long sentences and buoyed with thick paragraphs and thoughtful engagement with the world and the people around him.

Notably, there is no dialogue in the novel. Many of the characters converse in Tamil and markers of class, region, use of colloquialisms and changes of dialect that are otherwise visible when speaking and writing in Tamil would be flattened when translated to English, notes Arudpragasam speaking to the Sunday Times.

Notably, there is no dialogue in the novel. Many of the characters converse in Tamil and markers of class, region, use of colloquialisms and changes of dialect that are otherwise visible when speaking and writing in Tamil would be flattened when translated to English, notes Arudpragasam speaking to the Sunday Times.

In Tamil literature there is a strong emphasis on dialect and speech and while English offers modules of dialects, it would be wildly inappropriate to try to model Tamil dialectical difference in the dialectic differences that exist in English, reflects Arudpragasam. Rather than erase these cadences, conversations are in reported speech.

“It’s simply a moment in the South Asian novel or the non-white, non-European, non-Western English language novel where a historical contradiction appears that actually can’t be solved artistically because you cannot solve the problems of politics with the novel or with a work of art. This impossibility is there because of the ridiculousness of the idea of writing a novel in English about non-English speakers, and that exists because of colonialism and colonisation. It is also not my interest to pretend that such a problem doesn’t exist, or to pretend that there isn’t something ridiculous about me writing this novel in English, why are people reading it in English, why is it being sold abroad – things like this. For me, to void the reported direct speech and direct quotation is a way of acknowledging the historical contradiction of this novelistic act but also to try to dissolve it without solving it, in a way that acknowledges the insolubility of the broader problem,” he notes.

A starting point for the writing of the novel, Arudpragasam explains, was the relationship between Krishan and his grandmother and then it gradually expanded from there over the years.

The novel’s most tender moments occur in the interactions between characters. In Appamma and Krishan’s relationship, we see a portrait of familial tenderness and a reckoning of age, body and time. With Rani – a character in the novel with the closest physical proximity to the war – and Appamma, we see how a caregiver resuscitates an aging body with tenuous links to the world and how the act of caregiving anchors an aged soul also with tenuous links to the world. Krishan, looking back at his relationship with Anjum, an activist in India, reflects on the push-pull intimacy that tinged their relationship and “the tenderness that marked the transition between falling in love and actually loving someone”.

In his first novel, The Story of a Brief Marriage, Arudpragasam de-familiarizes the landscape, stripping it of name and extracting it from any political context. In A Passage North, under Krishan’s keenly observant gaze, detail is given to place.

A Passage North’s treatment of time and character echoes the modernist style of writers like Virginia Woolf. There is a simultaneous collapsing and elongation of time in the novel and the past, present and future are always linked – the action of the novel takes place across a few days but its narrative meanders between years. The stream of consciousness narrative opens out a rich, inner private world. In A Passage North, surface agitations (a call announcing a death, an email from an old lover) create ripples which rupture the “circular daydream of everyday life”. The characters are in a liminal state and strain against a restless solitude and yearning for something that cannot be named easily.

Like Woolf’s characters who felt “very young; at the same unspeakably aged” and had a “perpetual sense […]of being out, out, far out to sea and alone”, Krishan has a “strange sense of being cast out of time”, wrestles with a disquiet about the passing of time and often reflects on the dissonance between his inner and outer world.

Krishan’s stream of consciousness acts as a narrative scaffolding to link a variety of cultural and political material such as stories of the Buddha, documentaries and movies of the war, citizen archives of the conflict, Tamil and Sanskrit literature and more. In one instance, the novel carefully pieces together the events of the Welikada Prison massacres in July 1983. Although the event is remembered in the mainstream, details of its goriness are often expunged and Krishan lingers over Kuttimani’s story within the event – his wish to donate his eyes after death, the final act of brutality which ends his life in contrast to the words of the mural outside the Welikada prison announcing ‘Prisoners are humans’.

“I guess all of the material was tied together by this idea of desire, this idea of longing. Because all the characters in the book are creatures of longing, but it’s just that their longing is directed in different ways – away from the world that we are born into; towards the world that we’re born into but from which we are now being pushed away; towards a world that no longer exists but did exist in the past and contained the people who we love; or towards a world that does not yet exist but might come to exist,” says Arudpragasam.

In Arudpragasam’s novel, we are ultimately reminded that “memory requires cues from the environment to operate, can function only by means of association between things in the present and things in the past…” As A. Sivanandan wrote in his book When Memory Dies “When memory dies, a people dies. What if we make up false memories? That’s worse, that’s murder”. A Passage North constantly navigates what it means to bear witness and remember. The book is to be translated into German, Italian and Russian.

Arudpragasam always knew writing would be a key part of his life. The writing of The Story of a Brief Marriage was a solitary endeavour and he counts himself lucky to have the start and critical reception it had – he wrote it alone, his sister was his only reader, the book was sent to an agent, she liked it and the book was subsequently published.

The second novel was written over the course of five years in-between New York, New Delhi and Colombo. With A Passage North, there was an impetus to take on a technical and literary challenge and attempt a vastly different process. He decided to experiment with a sustained engagement with a single mind and a narrative devoid of dramatic context and plot. “The first book deals with a very violent situation and so I didn’t really expect that book to be published or to be received well or read widely, and I guess the fact that it was published made me feel okay, I did this thing that I felt like was not likely to work out and it worked out, now maybe I have more freedom to try something that’s maybe even less likely to work out,” Arudpragasam explains.

Arudpragasam, now 32, was born in Colombo and his first novel The Story of a Brief Marriage was translated into seven languages, won the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature and was shortlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize. He studied philosophy in the United States and received a doctorate at Columbia University. He is presently a Fellow at the Columbia Institute for Ideas and Imagination. Over the past six months, he has been working on another book.

Reflecting on writing as a private act and publishing as a public gesture, he likens it to throwing a party and having hosting anxiety.

“I guess in some ways publishing always brings the possibility of humiliation,” he says. “Because nobody ever asked you to write, and suddenly you’ve written something and you’re saying, read it. And it’s a little bit like throwing a party and being ambitious in who you want to have at the party, and how good a party it’s going to be, and you invite many people, and then you know there’s always the possibility that you will be left with maybe one or two close friends and a large number of people not coming to your party,” he explains.

“…But now I’ve thrown the party and the invitations have my name on it and now suddenly everybody will come or not come and if they come they may have a good time or they may not have a good time but there’s a chance I’ll be humiliated here. And I think that’s how I feel about it,” he pauses and smiles. “Does that make sense?”