News

Private sector intrusion: Veddah chief petitions court to protect forests and Adhi Vasi rights

Rathugala Veddah Chief

Veddah chief takes the Mahaweli to Court: Last week, this headline struggled desperately for attention in a sea of controversy over forests, protected areas, protected trees and bulldozers backed by politicians.

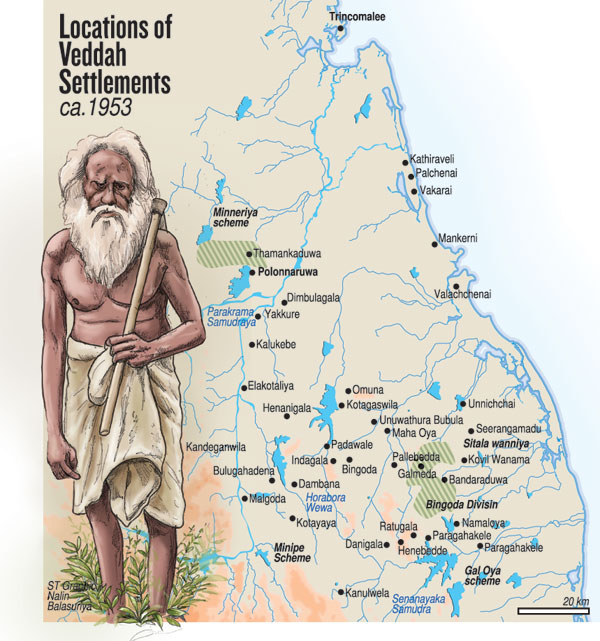

For years, the Veddahs or Adhi Vasis (ancient dwellers) have fought, with little success, the relentless tide of development that swallowed up whole their traditional rights and access to forests. In that sense, the Veddahs have been marginalised by both the development process and the conservation efforts in the country.

Hemmed in between vast agricultural expansion and fenced-off national parks, herded in to villages and concrete settlements, many old tribes died a natural death and were culturally assimilated or weaned off from forest-dependent lives.

Taking a stand against the last of their original clans losing traditional rights to a vast forested landscape in confluence of the Eastern and Uva Provinces, is Uruwarige Wannila Aththo, Chief of Sri Lanka’s only true indigenous population.

He is taking on the full behemoth of institutional, bureaucratic and political powers that hold the right to his tribe’s future in their hands. He names, as respondents, the Minister for Wildlife and Forest Conservation, the Central Environmental Authority, the Mahaweli Development Authority, the Forest Department and the Wildlife Department.

He requests the Court of Appeal to ensure the planned development under the Rambaken Oya scheme of the Mahaweli Authority conforms to the laws and safeguards ensured under the country’s constitutional and legal frameworks. He appeals to the Court to ensure that the respondents carry out their responsibilities and obligations under respective acts and ordinances.

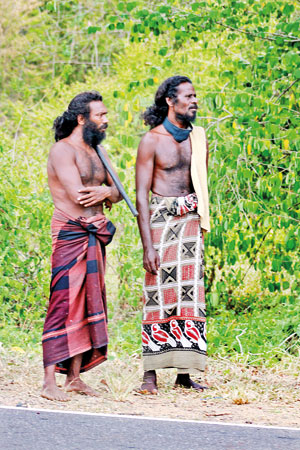

Veddahs believe their traditional way of life is under threat from haphazard development projects and deforestation

Pollebdedda is a remote village, where time has stood still partly due to its remoteness from anywhere important; but mostly because it borders the war-affected Eastern Province. For many years, even the main road that led from Bibile to Chenkaladi in the eastern coast was not passable. In this forgotten wilderness, the last of the original Veddahs — in Polbedda and Rathugala — continued their traditional way of life, gathering food, fruit, medicine and bees honey from the jungle and trading these for other consumables.

Although they are not duty bound by law, the Veddahs have acted as custodians of these lands for centuries, navigating the rolling savannah and high forests without a compass or google maps — hunting, fishing and gathering as they have done for millennia.

However, of late there has been renewed interest in developing the vast land resources in this hinterland. With the completion of the Rambaken Oya reservoir in 2013, a new zone was added to the Mahaweli Development Project, and it annexed vast areas of land, sections of which had been managed by the Forest Department for many decades.

The Rambaken Oya reservoir provides irrigation and drinking water to the parched downstream of Maha Oya, Padiyathalawa and some areas of the Batticaloa District. The Rs. 4 billion project was financed by the government and constructed using local engineering expertise. The reservoir’s 124 square kilometre catchment area includes some traditional Veddah territory — Bingoda, Pollebedda and Rathugala.

In their joint petition, Wannila Aththo and the Centre for Environmental Justice claim that the catchment forests of the Rambaken Oya are now being divested to the private sector for commercial agriculture, mainly to grow maize and corn for animal feed as part of the government’s new policy on saving import expenditure.

The Galwalayaya State Forest which is extensively used by the Pollebedda tribe is one such catchment forest being parcelled out for development. One private company, which has received around 500 acres, has begun stripping the land with bulldozers. It has been named as a respondent in the case.

The company has erected an electric fence around the property to keep elephants and other marauding wildlife at bay. The fear is that this is just the beginning of a large-scale parcelling-out programme that will further degrade the catchment of the reservoir and pollute the very waters meant for drinking in downstream villages.

In their argument, Wannila Aththo and the Centre for Environmental Justice call on the state agencies to abide by the law and take action as stipulated under the National Environmental Act of 1980, the Forest Ordinance of 1907 and the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance of 1938 to prevent wanton clearing and illegal fencing of afforested lands in this catchment area.

In a number of previous cases, Sri Lankan courts have upheld the public interest principle that the state and its agencies are custodians of the natural resources in the country on behalf of future generations. In the petition, Wannila Aththo’s plea is that the protection of the forest for future generation, and the rights of his people to continue their way of life be recognised as their fundamental rights protected by the laws of the country.

The Veddahs’ plight is not unlike many other nations’ indigenous tribes, whose right to land and resources are trammelled by agencies working for both conservation and development. In the initial Mahaweli Development programme, entire Veddah settlements were cleared without so much as a blink. Villages like Dalukana in System B and Henanigala in System C were overrun by irrigated agriculture and settlements. The remaining tribes were assimilated into villages. Veddah population is down to less than 0.05% of the population (around 10,000 people).

The Chief’s own clan has now dwindled to a mere tourist attraction for most part. Their constant battle to be recognised for their hunter-gatherer ways and their right to access forests — now fenced off as Maduru Oya National Park — have been on-going for the past 30 years, without much resolution.

The uneasy mistrust between conservation agencies (Forest and Wildlife Departments) and the Veddah community and the reluctance to recognise their right to the forests stem from a few quoted incidents of misdemeanor.

Veddah identity cards issued by the Wildlife Department permitting them traditional hunting and gathering of honey and herbs within the Park were later withdrawn due to alleged misuse and use of firearms instead of bow and arrow. However, for Veddahs, the forest is part of their DNA, imbued into their physical and mental wellbeing — and preserving their culture and traditional knowledge is incalculably important to us as a country; considering they are the oldest inhabitants of this island.

The older Veddah people lament that their children and grandchildren have grown up in brick-and-cement houses and away from the jungle — with their traditional knowledge and practices and food patterns disrupted by ‘enforced modernisation’’.

Pollebedda and Rathugala clans still retain many traditions and characteristics of the original Veddahs, lost forever in other areas.

Internationally, the rights of indigenous people are strongly considered in development projects. Multilateral and responsible bilateral donors now shy away from projects that could lead to loss of traditional hunting/fishing/gathering lands of such remaining tribes. As such, in this case, the Veddah Chief’s plea cannot fall on deaf ears — whatever the nuances of the law and limits of agency mandate that may be argued in court.

The Veddah community have a right to their way of life, and this way of life can actually be an asset to conservation. Short-term development aspirations of this generation cannot take away the rights and lifestyle of a people who have been using these lands for millennia.

They are this land’s original dwellers — Adhi Vasis. But they have never considered nature (land or forest; stream or rock) a thing to ‘own’ and fence away. Therein is the point of contention. Are we mature enough as a society to recognise the Veddah people’s inalienable right to these forests and their way of life? Are our conservation agencies willing to consider that Veddahs could be guardians of the jungles and not a threat? If development is imperative, can we come up conservation-oriented models that support the Veddah lifestyle?

Remember, we will be judged by future generations on the decision we make today — on our forests, on our land and the remaining Adhi Vasis.