“NATIONAL INTEREST” on ECT development project

File picture of the SAGT terminal

The loud cry of the port workers today backed by the shadow political economy, echoes the misconceptions around the landlord system of port management. The error is not with the port workers who seem to believe in their cry simply because they have been repeatedly misled.

What is regrettable is that, it is only the port workers who seem to show an interest in this matter of national importance. This is because a port providing services to both domestic and international trade should have more than just its workers as stakeholders. These stakeholders should lend their voice to correct these misconceptions.

The stakeholders of

national ports in the country

include all of us as below:

1. Sri Lankan nationals – The ports are the heart of the nation. Thus, any decisions have to keep national interest as priority.

2. Port trade unions- Trade unions are there by design to ensure employee interest over others.

3. Regional competitors – Nations in the Indian sub-continent who can squeeze / deactivate transshipments through ports in Sri Lanka.

4. Global investors and large international traders: They bring in much needed Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs), expertise and help promote efficient seaborne trade.

5. Ports regulators: Should manage the regulations relating to administrative, landlord and harbour control.

In order to make the reader understand clearly, let me share a recent statistic of the current status.

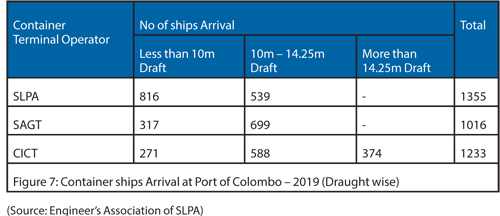

The Colombo Port has three main terminals. Two managed under the landlord system (SAGT, CICT) and the Jaya terminal, managed, run and operated by the SLPA. The below table indicates the performance in 2019.

As we can see from the table, it is only the CICT terminal (one of the few such terminals in the world for handling 18000 TEU container vessels), that has the capacity to accommodate ships of more than 14.25m draft. Therefore, it is important that the country expands port investments allowing for business from deep sea vessels at other terminals. By delaying such investment which is the current discussion and has been delayed due to trade union action for over six years, the only party gaining is the CICT (85 per cent owned by China). Can you see the potential of the port that is getting wasted due to inaction?

Sri Lanka has the potential to emerge as the Maritime Hub of the Indian Ocean with ability to facilitate deep sea vessels. Despite this potential, Sri Lanka has not been able to maneuver the tricky waters of internal politics in moving ahead. Consecutive regimes have been misguided in driving the country to reach its full vision for proper port development. The latest news headlines relating to the East Container Terminal development makes it necessary for us to revisit the very foundations of Sri Lanka’s port development and its unique status today (see below) in order to understand the true nature of the issues at hand.

A well negotiated landlord system would bring in benefits to the country, by allowing Sri Lanka reach its true maritime potential. Therefore, the proposed action by the government with regard to the ECT is not only timely but also addresses the “true national interest” to bring in efficiencies through the private sector whilst ensuring much needed foreign income, employment opportunities and business.

Types of Public Port Management

The basic port management systems of public ports operating worldwide (Thoresen, 19XX), are described in literature as follows:

(a) Tool (Resource) port (also known as the “French Model”): The port owns the land, infrastructure and fixed equipment, provides common-user berths and rent-out equipment and space on a short-term basis to cargo-handling companies and commercial operators. (Eg. Ports in Sri Lanka from 1854 to 1979, minor ports)

(b) Operating (service) port: The port provides berths, infrastructure and equipment together with services to ships and their cargo. (Eg: Ports of Sri Lanka from 1979 to 1999)

(c) Landlord port: For larger ports this is the most common system where the port owns the land and basic infrastructure and allows the private sector to lease out berths and terminal areas.(Eg: Ports in Netherland-Rotterdam Port & regional ports, Ports in Singapore( PSA ++ ))

(d) Private Port: Private ports do not belong to any of above categories – (Eg. Hambantota Port)

(e) “Hybrid” type Port system – used in this article to refer to the current port management system of Sri Lanka, i.e. a combination of “Landlord”, “Service” and “Private”. It is a complex, inefficient and uneconomical per expert analysis.

Port Management Best Practice

How are public ports managed elsewhere? All major public ports in the developed world practice the landlord system. There are private ports as well in the developed world. Ports in developing world are in transition from ‘service ports’ to ‘tool port’ and subsequently ‘landlord port’ as the final destiny. Singapore transition was made from tool port to landlord port in late 1960’s, which was an easy jump. In Sri Lanka, transition was made in the reverse direction, from a Tool port to Service port and now the big jump from Service port to Landlord port is a painful process.

- What is best practice? The best practice for ports in the developing world is “Landlord” where state engages in statutory duties to the nation, and the private sector engages in connected commercial activities in a level playing field regulated by the state.

- Is there a regulator for different aspects as well as other players? Yes. In the telecom industry re-structuring, public land is vested with public operator, and private operators invest in private land. Only an administrative regulator – (TRC) will do statutory duties.

But, in the ports industry, for all public ports and private ports as well, the sea bed or the river bed is public property and not considered as land, but identified as “Roads” in transportation networks. All infrastructure in the public transportation industry are developed on roads (public property) and it involves a landlord regulator for attending to statutory duties of roads. In land transportation, the Road Development Authority (RDA) is the landlord regulator for roads, and inland waterways while the CGR is the landlord regulator/operator for rail roads. The administrative regulator for land transport is the National Transport Commission.

In regulating ports, there comes another regulator, for sea lanes, as “Law of the Sea” is different from “Laws of Land”, where ships enter in coastal waters of harbour basins and sea lanes developed by the port engineer. Regulatory duties of sea lanes are entrusted to a Master Mariner, better known as Harbour Control regulator. As for who the landlord regulator (i.e the regulator who attends to statutory duties of ports) – it is unclear. But as per statute, this function can be fulfilled by the Director (Technical) of the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA).

The three regulators, Administrative, Landlord and Harbour Control have to work in unison, but different regulatory functions, as roads and sea bed beyond high water line are the property of the state, and public administration of functions similar to duties of the TRC to create a level playing field for all stakeholders of the ports industry.

History of Port Management

in Sri Lanka

- Colombo was the main recognized deep-water facility close to the East –West shipping route in competition to Singapore, Aden and Dubai.

- The British used “Tool ports” port management system, with private port operators handling operational activities, regulated by the Traffic Department of Harbour Board / Colombo Port Commission.

- Colombo Port was nationalised in 1958. The consequent politicisation of the port led to ship operational delays resulting in losing both transshipment business to regional competitors as well as shifting of domestic trade to ports of Galle and Trincomalee.

- The “Tool ports” port management system, was continued until 1979, with the public port operator handling operational activities, with disastrous dents in ports industry.

- With the introduction of the open economy in 1977, Colombo commenced development activities to handle containers with technical assistance from Japan.

- Given Colombo port’s deep water facilities, with the expansion of containerization, giants of international seaborne trade, wanted to re-introduce transshipment activities in Colombo, mainly to handle large volumes of containerised cargo to and from the Indian Subcontinent.

- The SLPA was created in 1979 – by introducing the “Operating/Service Port” system of port management.

- From 1979 until 1999, the SLPA handled all port terminal operations as the sole public port operator for all ports, together with regulatory functions under statute. These included being the regulator for national port administration, national landlord regulator and national harbour control regulator.

- There was a major change in port management in container operations, with creation of the landlord system of port management in 1999.

(The writer is a port management consultant with over 50 years of experience having also served as a senior official of the SLPA. This article was submitted before the government on Monday decided to allow the ECT to be run solely by the SLPA).