News

Second COVID-19 outbreak likely if curfew is ended too soon

Sri Lanka held its breath with hopes that if a cluster of COVID-19 patients does not break-out next week, all the positive steps taken in the country would help flatten the disease curve.

Pointing out that the stringent measures put in place to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in Sri Lanka should not be relaxed, the Director General of Health Services, Dr. Anil Jasinghe said this week that the quarantine period of those who returned from Italy are in the final phase. At the moment, they have to keep track of patients from countries such as Indonesia, Dubai and India and trace all those whom they may have met.

Kelaniya: The public adhering to social distancing while waiting in line at a pharmacy. Pic by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

If the lockdown is relaxed, Dr. Jasinghe warned, and the social distancing and hand hygiene advocated repeatedly by the health authorities are not followed stringently, there could be adverse effects.

Strong voices of reason in support of Dr. Jasinghe’s cautionary note came from expert health professionals.

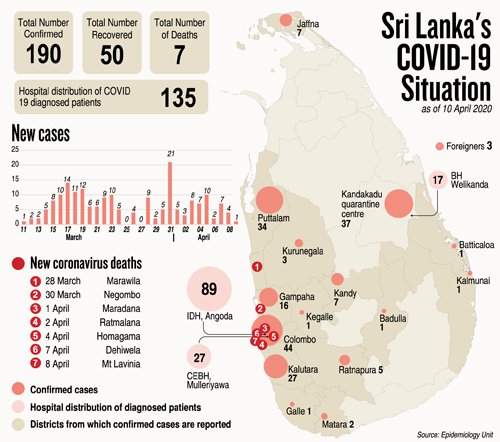

Clearly showing the peaks of the number of COVID-19 confirmed cases in Sri Lanka, the College of Community Physicians of Sri Lanka (CCPSL) has stressed that ending the curfew too soon could lead to a second outbreak, while enforcing it for too long could further cripple the economy and public morale.

Urging that it should not lead to a human tragedy as in other countries, the CCPSL, the apex professional body in public health, called for “calculated decision-making” considering all facets of the epidemic and the basic demands of the public.

The CCPSL says that mapping the districts where cases and contacts are most and relaxing curfew in other districts and continuing the ban on inter-district migration are some of the strategies that could be adopted for a more targeted response. Essential services such as healthcare centres, supermarkets, groceries, banks and pharmacies should be kept open daily and people allowed to walk to these places ensuring physical distancing. The local industries should be facilitated to open early, while all transport should only allow 50% of the seating capacity to ensure physical distancing.

Taking stock of the situation as at April 8 (Wednesday), the CCPSL states that there were 186 confirmed cases with seven deaths.

Taking stock of the situation as at April 8 (Wednesday), the CCPSL states that there were 186 confirmed cases with seven deaths.

Three peaks are obvious from its graph:

- March 17 – 14 confirmed cases were detected

- March 23 – 10 confirmed cases were detected

- March 31 – 21 confirmed cases are detected

The CCPSL states that Sri Lanka is now in Stage 3 or ‘Clusters of cases’ within families or in villages. Most cases of limited transmission would be linked to chains of transmission of either being exposed to a family member (family cluster) or to neighbours or other close contacts (village clusters).

While underscoring that the country has taken every effort to prevent progression of the disease to the next stage – Stage 4 which is community transmission, the CCPSL stresses that if Sri Lanka moves to this stage it would be “very difficult” to stop the increase of cases. This would be cases without an epidemiologic link being common in the community.

In an outbreak, Stages 1 and 2 which Sri Lanka has passed are ‘no reported cases’ and ‘sporadic cases’ (one or more cases, imported or locally acquired) respectively.

Some of the proposals for strategic planning in the face of the danger of COVID-19 put forward by the CCPSL are:

Streamline national and sub-national coordination – Effective coordination at both ground and national levels is the key to success. Revisit this aspect, looking at coordination from top to bottom between the curative and public health sectors and also among relevant divisions within each sector. It is apparent that some of the higher level stakeholders are not fully involved and there are also multiple instances of non-compliance with guidelines at ground level.

Scientific prediction of the epidemic – A pre-requisite of the epidemic response is the availability of a near valid country-specific model to predict the progression of the epidemic. This would address the burning issue of the public – when and how will this epidemic end? This task should be entrusted to a panel of experts representing different fields and the model tested with actual data. The CCPSL laments that at present, there is no ready access to much needed COVID-19 data.

Scenario-based approach – Potential country scenarios should be worked out and strategies formulated beforehand by a team of professionals with public health experience. Some scenarios Sri Lanka may encounter: Scenario 1 – Community transmission and exponential increase of cases with preventive measures going out of control (This would be the worst scenario); Scenario 2 – Current scenario with sporadic cases and no burden to the health system; Scenario 3 – Lowered health system capacity due to infected healthcare workers or reduced supplies; Scenario 4 – Second wave of the epidemic.

Exit strategy of the modified ‘lockdown’ – The modified ‘lockdown’ strategy is to flatten the curve and gain time for the health system to respond. This alone will not work and simultaneous case detection, contact tracing and isolation/quarantine should be employed. The purpose of this strategy is to reduce reproduction of the virus (the number of secondary cases which one case would produce in a completely susceptible population). It is essential to review whether the country has achieved this goal.

Updating the public – Need for clear-cut regulations for media spokespersons, to prevent confusion among the public. One spokesperson should be officially responsible for giving updates on the line-up.

Meanwhile, six senior professors from universities across the country also provided recommendations for an ‘exit strategy’ from the lockdown.

They include continuing the current level of restriction for now and a review after the New Year. If the level of transmission is not high as evidenced by the daily number of new cases and a slow doubling time of cumulative cases, the curfew can be relaxed in stages, district-wise (one district per province on given days of the week). The chaos that occurred on March 24, when curfew was lifted for just a few hours, should not be allowed to recur. Areas with high numbers of patients could be cordoned off and kept under stricter control measures.

Supermarkets, hospitals, food markets, more petrol stations and pharmacies could remain open for a period of time, to be decided by the Task Force, on a daily basis and each household issued one pass to allow one person to go out to get essentials in their own neighbourhood. Travel between towns and cities should be discouraged, state Prof. Janaka de Silva, Prof. Sarath Lekamwasam, Prof. S.A.M. Kularatne, Prof. Sisira Siribaddana, Prof. Saroj Jayasinghe and Prof. Kamani Wanigasuriya of the Universities of Kelaniya, Ruhuna, Peradeniya, Rajarata, Colombo and Sri Jayewardenepura respectively.

| Hotlines – 1390 & 1999 | |

| The Health Ministry has introduced two new hotlines – 1390 and 1999 – for any medical emergencies.These hotlines will respond promptly in all three languages, announced the Director-General of Health Services, Dr. Anil Jasinghe. |

| Request to self-quarantine for two more weeks after returning home | |

| All those who completed their 14-day quarantine period at the centres being run by the Tri-Forces across the country have been instructed to be in self-quarantine once they return to their homes for two more weeks.As of April 8, 3,386 persons had completed their quarantine in 40 centres, 36 run by the Army, three by the Air Force and one by the Navy.Meanwhile, 1,287 persons are in quarantine at these centres currently. |

Child had no travel or contact history

Has low-grade community transmission begun? This is the question being asked by Negombo Hospital’s Consultant Paediatrician, Dr. LakKumar Fernando, under whom came the second COVID-19 patient, who sought admission to that hospital.

While commending the good measures taken by the health authorities, Dr. Fernando points out that when looking at the spread of the new coronavirus, in some ‘confirmed’ cases there is no clear travel history to a high-risk area or contact with another confirmed case.

It was around 10 p.m. on Friday, April 3, when a 4½-year-old boy came to the Preliminary Care Unit (PCU) of the Negombo Hospital. He had no history of high fever at all. He was a known wheezer and was on inhaler therapy. He came with an exacerbation of wheezing without an apparent reason. The viral association of an exacerbation of wheezing in the current lockdown state where other reciprocating factors were not there, was of concern.

“Usually, when a child who is wheezing comes in the night, the wheezing is expected, through our experience, to increase in severity towards early morning and needs monitoring and treatment,” says Dr. Fernando, explaining that it would be tricky not to take him to the Children’s Ward but send him to the COVID ward that had less supervision.

In the light of the COVID-19 pandemic, the two Children’s Wards 8 and 15 had made specific arrangements to admit all those coming in with respiratory symptoms to Ward 8 only, it is learnt.

“When my Senior House Officer (SHO) called me and told me that the child did not have a significant travel or contact history, I asked her to go to the PCU with protective wear and assess the patient from a distance, with the help of a triage doctor. This was because Ward 8 has some limitations with the personal protective equipment (PPE) and I wanted to limit the exposure of staff and other patients in case it was COVID-19,” says Dr. Fernando.

The child’s father was employed in a fibre-glass factory in Jaffna with no contact with foreigners or people who had come from abroad. He had returned from Jaffna on March 3, a month before, and had not gone anywhere else since then, he says.

The plan was to take a nasopharyngeal sample from the child at 5 a.m. the next day and get the negative or positive results for COVID-19, the same day by noon.

However, there were no swabs available at the hospital and the sample from the child who was in the COVID-19 isolation ward could only be sent on Saturday evening. ‘Positive,’ came the result on Sunday, April 5 around 3.30 p.m., says Dr. Fernando, explaining that during the nearly two days the child was in the isolation ward, more than 20 other patients were exposed to him, while the child underwent nebulizing, as inhaler therapy was not enough, in a somewhat open setting, a few times as well.

“Six others were in the same cubicle,” he says, adding that the child was then transferred to the National Institute of Infectious Diseases (NIID) and is on the road to recovery.

Here are Dr. Fernando’s deductions from this lesson – There may be a low-grade community transmission; more than 50% of children affected by COVID-19 do not present with fever, any time during the illness, which has also been observed in China; the spread of disease in a hospital setting is easy; COVID-19 isolation units, like quarantine centres, can be a source of infection as well; and there is a need for a better system of quarantine for healthcare staff who get exposed, as home isolation may not be feasible depending on the facilities available.

“It may be time to think that everyone who comes in with a respiratory issue at least in high-risk areas, is a potential COVID-19 patient until test results come in negative,” is what Dr. Fernando believes.

| Those who died of COVID-19 in Sri Lanka | |

| March 28 –The first death of a patient, 60, from Marawila. He had contact with an Italian tour group. He died at the National Institute of Infectious Diseases (NIID).March 30 – The second death of a patient, 64, from Kochchikade, Negombo. He had reportedly attended a wedding in Jaffna. Initially admitted to the Nawaloka Hospital in Negombo, then to the Negombo District General Hospital, he died there while awaiting transfer to the NIID.April 1 – The third death of a patient, 72, from Maradana, who had contact with a returnee from Saudi Arabia. He was pronounced dead on admission to the NIID.April 2 – The fourth death of a patient, 58, from Ratmalana who had returned from a pilgrimage to India. He died at the NIID. April 4 – The fifth death of a patient, 44, from Homagama who had returned from Italy. He was in a quarantine centre when he fell ill and died at the Welikanda Hospital. April 7 – The sixth death of a patient, 80, from Dehiwela. He died at the NIID. April 8 – The seventh death of a patient, 44, from Mount Lavinia who had returned from Germany. He died at the NIID. Sri Lankans who died Here is some information on Sri Lankans who have died in foreign countries that the Sunday Times found on the web, while a Foreign Relations Ministry source said that they had no official intimation of these deaths. March 25 – A 59-year-old Sri Lankan, from Pungudutivu in the Northern Province, who was living in Switzerland. March 29 – A 70-year-old retired doctor and another 55-year-old Sri Lankan from Maharagama who were in the United Kingdom. April 4 – A 75-year-old geriatrician, Dr. Anton Sebastianpillai, of Sri Lankan origin who worked at the Kingston Hospital died in the United Kingdom. A historian, he became popular in Sri Lanka when he wrote ‘A Complete Illustrated History of Sri Lanka’ in 2014. The other books to his credit are ‘A Dictionary of the History of Medicine’ which won a British Medical Association (BMA) medical book award; ‘Dates in Medicine’; and ‘A Dictionary of the History of Science’. April 5 – A Sri Lankan, a former Air Lanka employee, died in Melbourne, Australia.

|

| How people may get COVID-19 after quarantine? | |

| They had ended their quarantine period but later contracted COVID-19. As many people were focusing on this issue, the Sunday Times asked several experts how this would be possible.In the two cases reported so far, a 34-year old from Matugama who had returned from South Korea on March 10 and had undergone 14 days of quarantine at the Kandakadu centre, tested positive 10 days after his return home. He had then gone to the Nagoda Hospital, Kalutara, with complaints of stomach pain and phlegm.Another person from Akuressa who had been in quarantine and returned home after the specified period had also tested positive.This is possible, said many health sources, explaining that these persons may have got exposed to someone with COVID-19 a few days before leaving the quarantine centre. Those persons to whom they were exposed could have either been symptomatic or asymptomatic. The other likelihood is that when they returned home, they may have come into contact with someone who was affected by COVID-19, who too would either have been symptomatic or asymptomatic. Another hypothesis being put forward is that as this is a new virus, there could be some people in whom the incubation period (the time between exposure to an infection and the appearance of symptoms) would vary, from the usual 14 days. This is usually an exception to the rule.

|