Bentota Beach Hotel: The story behind an iconic hotel

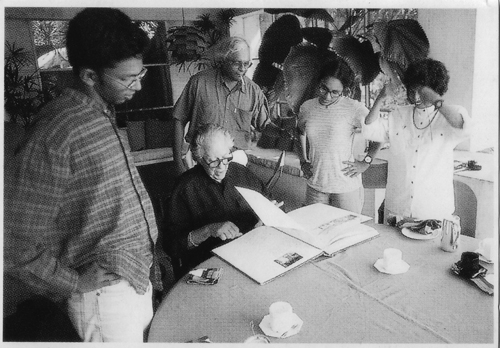

Geoffrey Bawa with the Raheem family at his residence Lunuganga in 1990

A little short of two centuries ago, Bentota remained in the consciousness of travellers as a delightful destination. In Simon Casie Chetty’s compilation in the Ceylon Gazette of 1834 he comments on its desirability as a calming and restful place: “A delight full village in the provinces of Walallawetty Korle, in the district of Galle, situated off the left bank of the river of the same name 12 miles south of Caltura” and notes further, “fish is to be had here in great plenty, and its oysters have been celebrated for their exquisite flavour. There is a church of considerable size, and a rest house for travelers”.

A century later, the 1938 Automobile Association annual publication for motorists echoed the same, accompanied with an ominous warning: “Bentota. S.P. Col. 38 miles. Rest House. This was the half-way house between Colombo and Galle in the old coaching days. Is reputed for its edible oysters. The Rest House is near the mouth of the Bentota river, which is infested by crocodiles but presents fine river scenery.”

By the 1930-40s the rest house renovations obliterated the last remains of the V.O.C.’s (Dutch East India Company) stockade. But in the1960s in Geoffrey Bawa’s architectural layout, it resurfaced again!

After the country’s independence in 1948, the revitalized Department for Tourism Management made further improvements.

Ironically in April 1958, Bevis Bawa (Geoffrey’s brother) was awarded the commission to improve the accommodation and lay out a new garden. A hugely talented personality, Bevis was a great innovator and deployed local craftsmen and materials to create Brief, a bungalow set in a charming garden in the 1940s. A designer and innovator of architectural interiors, Bevis took pride in utilising local materials and craftsmen. His inventive skill in the re-use of terracotta tiles (much used by Dutch builders), built-in masonry seats, concrete slabs with embossed leaf designs, brick carved light niches, paper lanterns, internal ornamental pools, murals in gold leaf, and landscaping courtyards with Temple flower trees (Araliya) are best illustrated in Brief.

Nail Sculpture in copper, brass, lead, steel and iron nails. 5ftx5ft. art work completed 1970 by Ismeth Raheem Photo by Luxshman Nadaraja Jan 2020

Geoffrey Bawa adapted and incorporated many such design elements in the Bentota Beach Hotel. Assisting Bevis was Donald Friend, Australian artist and sculptor, a co-partner in the venture (a little-known fact). As a guest at Brief, he created arresting paintings and sculptures from January 25, 1958 to July 22, 1962.

Friend’s diary entries reveal their activities in the Bentota rest house.Working at a frenetic pace, Friend cast garden sculptures, pots and decorative gateposts at Bevis’s behest, but sadly few records exist of their work.

Geoffrey Bawa’s borrowings from tradition went a step further in the hotel at Bentota by casting the main public areas around a large landscaped courtyard evident in examples of early domestic architecture-the placement of living spaces around a courtyard. Many architectural devices recycled from the past followed. Louvered doors, windows, classical timber furniture and fittings took their cue from existing models.

Architectural historians like to remind us that these prototype design elements were an essential part of Sri Lankan architecture long before such devices were deployed in the buildings of the colonial period.

The 1960s was a turbulent time in Sri Lanka -social upheaval, political insecurity, financial instability was the norm. But through it all architecture and the arts survived and made their presence felt. By May 1970, new draconian measures were undertaken by the Ministry of Finance of the new Government to safeguard the country’s depleted foreign exchange reserves which resulted in a ban on the importation of foreign architectural and building materials. Likewise, these restrictions had impact on materials used by the artists and craftsmen as well. Dyes (for batik and handloom production), water colours, oil paints, sable hair brushes, quality drawing paper, were unavailable in the market.

Interior view of present hotel with Raheem’s work including Gold and Silver leaf painting. Photo; Luxshman Nadaraja Jan 2020

Early in the 1960s there also arose an awareness among a small coterie of architects in search of inspiration from the much maligned and little understood architectural features of vernacular domestic and religious buildings.

By 1962 – 63, a team of four including Ulrik Plesner (Bawa’s Danish architectural partner), Barbara Sansoni, Laki Senanayake and myself accomplished a much overdue documentation of 16-18th century domestic and vernacular buildings including forts, temples, residences, courtyard houses -examples of architecture from Jaffna in the North, and Galle in the South, and many other sites in-between.

Geoffrey Bawa drew much inspiration from the architectural designs and details which focused on use of indigenous materials illustrated in the portfolio of drawings, and ideas that inspired were incorporated in his own work.

His empathy is reflected in the supportive letter he drafted in 1963 addressed to the Sri Lanka Science Council on my behalf. He also emphasised that he was well aware that as far back as 1959, when we first met, that this was a worthwhile study and interest we both shared.

Bawa handpicked a team of builders who had vast experience of constructing buildings in the traditional way. The head baas Shabdeen was a genius in translating Bawa’s drawings – how to construct buildings pleasing to the eye. Shabdeen had an incredible store of knowledge on how traditional materials could be incorporated in an aesthetic way into a modern hotel building.Within a few hours he would set up a real-life model with strings and bamboo poles –a three-dimensional full-scale profile of the building based on Bawa’s design.

Geoffrey Bawa’s office Edwards, Reid and Begg had a relatively small staff and relied on a few of us to translate his miniscule sketches. It consisted of Laki Senanayake – the most senior and trusted draughtsman and designer of Bawa’s team, and Anura Ratnavibhushana, Pheroze Choksy and myself who were schooled and trained in Copenhagen, Denmark and had returned as full-fledged architects in 1969. We formed the rest of the team.

We were the “The Set Square and T-square Set”. All our work was drafted on wooden drawing boards almost five to six feet long and three feet wide. The drawings were drafted on tracing paper with special pencils and if Bawa had to impress a client the original drawings were inked, and printed.

In 1970, drawings were executed with antiquated drafting instruments like those used as far back as 1500 in Renaissance Europe by architects of the calibre of Palladio, Leonardo Da Vinci and Brunelleschi. It seemed the production of architectural drawings had not changed for 500 years- at least in Sri Lanka!

In the 1960-70s there were no special pens with ink- cartridge or capsules. Only unwieldly pen holders in timber with interchangeable brass script nibs. Ink for drawing was supplied in pots or bottles. Chances of accidental spills were high.

The production of printing plans was done in the most primitive fashion – placed in a chamber of ammonia and then developed by sunlight.

Looking back, many of these painfully executed drawings have now become collectors’ items.Often illustrated in exquisite detail, they specify proper setting of furniture, paintings and wall hangings even the individual species of trees, plants and birds-which were likely to appear at the building site.

True to Bawa’s concept in many of his architectural projects he integrated the works of some of the leading artists and craftspersons.

By the 1960s he founded a coterie of artists, sculptors, weavers and printers to decorate the architecture he had created – a guild of designers under his guidance faithfully using traditional design techniques and materials in the most effective and contemporary manner.

To meet the busy construction schedules, Laki and I would spend several weekends at Lunuganga – Geoffrey Bawa’s country residence. Creating art works for the numerous residences and hotels which by the 1970s ranged from Mauritius to Bali and sometimes for Geoffrey’s Colombo residence, Laki and I would compile a list of birds, trees of interest in the surrounding garden at Lunuganga. The photograph accompanying this article- shows Geoffrey Bawa explaining how the list of birds was recorded in the Lunuganga visitors’ book, recorded in 1972 to my family.

Geoffrey was loath to have any outsider working in the interior of his architectural projects. For the Bentota Beach Hotel project he had a small guild of artists and craftspeople hand-picked by him. Of the more important and prolific were Ena de Silva, Barbara Sansoni, (handloom ceiling), Laki Senanyake (peacock sculpture) and myself (14 black and white panels, a gold leaf painting, and a nail sculpture). These four artists between them created artworks for the interior that now forms a part of the main lounge.

The batik ceiling cloths (Reception) were planned and executed by Ena de Silva. With Laki, a partner in the firm of Ena de Silva Fabric in 1970, he played a significant role in designing the batik ceiling pieces. Both of us would carry out various tasks for her at her workshop.

The recent rebuilding and renovating the Bentota Beach Hotel have been principally due to Channa Daswatte’s herculean effort. He gave us artists and architects the space to revive what may have been lost forever.

(These records of Bentota — both rest house and Beach Hotel were culled from documents, gazetteers, annual reports, drawings (architectural plans and sketches), photographs, articles in the public press and Donald Friend’s diary entries between 1963-1970)