Import substitution in higher education

View(s):

A couple of days later, Stafan – one of my colleagues from the Sri Lanka branch of a foreign university, called me looking for some information. He wanted to know the “academic year” – starting and ending months, in the Sri Lankan universities.

“If you could find it anywhere, please let me know too.” I replied.

He thought that I was joking, but actually I wasn’t. He had also browsed the relevant Internet sites, and having had no success, then called me.

I explained to him about how different universities in the country follow different academic calendars, and even within the universities, different faculties follow their own calendars. But usually, the beginning and the end of the academic year often get changed so that it is not fixed for a particular month of the year.

And it cannot be fixed too, because the academic year gets extended more than the calendar year for various reasons, including trade union actions by different parties at different times. This means that there is no such thing as a fixed academic calendar in Sri Lankan universities, unlike in other countries.

My answer, anyway, confused Stafan, who asked me again: “Then how do you function on par with international university calendars, such as the Commonwealth universities?”

I responded: “We don’t, and why should we? We don’t mind if foreign students apply to our universities or not. In fact, they don’t. We can’t recruit foreign professors just like in any other profession in Sri Lanka. We don’t mind if they are here or not. And in fact they are not, and we are happy about it too. When we don’t have much to do with in line with international university systems, why should we bother about our academic calendar?”

I continued: “The first resistance should come from our clients – the students, but they don’t have a choice, and they don’t have to pay so that they are bound to receive whatever we offer. Do you know that our university students are already 3 or 4 years older than the university students in other countries? But it is okay for everybody, and we are doing fine with all what we have.”

Academic year

Academic year in a university is a period of 12 months for all academic activities, which include teaching, examinations, and receiving results, as well as the semester breaks, and vacations falling within the year. Usually in Commonwealth countries, the academic year starts in September or October, and ends in August or September the next year, completing 12 months of academic activities.

The international academic year is not a haphazard selection. It allows the students sitting post-secondary national examinations (such as GCE A/L) in May/June and getting the results in July to apply to the universities, and start university education within 2-3 months. Many universities have now adopted a system which includes more than one academic year. In addition to the main academic year, those students who were unable to get admission to a university do not have to wait another year to find a university, since within a few months’ time another academic year starts.

Another flexibility is that most of the international universities allow the prospective students to apply for the university admission even before they get post-secondary examination (GCE A/L) results. Because of that, the universities have made the selection process more efficient and a less-cumbersome activity of the year, while the students also have a more flexible and adequate time for preparation.

Import substitution

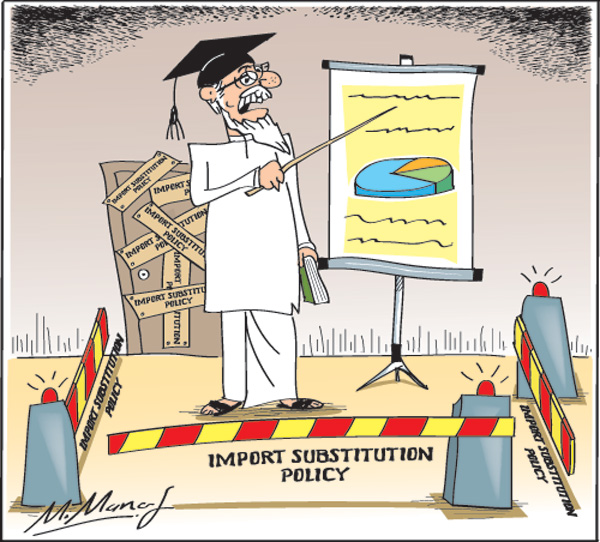

Whenever I think of the dominant features of our university system, I cannot ignore the notion that it is still an “import substitution” activity that we have preserved in Sri Lanka.

Import substitution is an abandoned “development strategy” in the world. Sri Lanka had it too for more than 20 years (1956-1977). The outcome of the strategy was miserable in Sri Lanka as well as elsewhere. As a result, the import substitution strategy disappeared with the introduction of an export strategy after 1977, although some may still worry about how to resurrect it.

Even though import substitution in Sri Lanka disappeared as a “strategy”, some of its “left-overs” still remain intact. University education appears to be one of them.

What is import substitution? A main feature of import substitution strategy is the isolation from the rest of the world. It is an “inward-oriented” activity catering to the local market. Sri Lanka had initiated at that time – from big industries such as steel, textile, paper, cement, sugar, and liquor to the small ones such as soap and match box.

Guaranteed market

They were all catering to the local market, because these products could not be sold in the international market. No one would buy them because of poor quality. Why they were poor in quality was because there was no competition. Competition had been curtailed by import controls so that import controls acted as a protective barrier.

Even if they were poor in quality, they had a secured monopoly market. Local people who didn’t have a choice, anyway had to buy them. Therefore, businesses didn’t have to worry about what quality of products they sold, because there was a guaranteed market.

These industries sometimes had to stop running the factories for various reasons including trade union actions or no input supply. Even if just a single input like raw material, perhaps water or electricity or diesel was unavailable, the factories stop working. Some factories stopped operations for months until they received raw materials. Workers were idling, but they received their salaries although they didn’t produce anything.

I was wondering as to which of the above features is prevalent in our higher education system. There is no international competition or even local competition. There is a guaranteed local market because of the lack of choices. Out of about 300,000 students sitting the GCE A/L examination, catering to 10 per cent is not an issue. The demand is basically for the “certificate” more than for knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Wholesale jobs come from the government, which does not care about what subjects the graduates have learned.

Education hub

Sometimes, we boast about Sri Lanka’s ability to transform itself to an “international education hub” and cater to South Asia, East Asia, and Africa. Even going beyond that, we talk about the ability to cater to the students in Western countries who can acquire the same qualification at a cheaper cost in Sri Lanka than in their home countries.

Actually, the point is true and, many countries in Asia have moved in that direction exploiting the global opportunity. In order to become a global education hub, Sri Lanka should have an established track record for exporting and importing knowledge. Exporting knowledge means that our university system must have been catering to the global education demand, but generally we don’t. Importing knowledge entails recruiting “foreign academics” to enhance our university education with global knowledge, but generally we don’t.

An “international education hub” means, in other words, smashing its import substitution impasse and expanding the education system towards the global market for knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Moving away from import substitution requires deregulation and autonomy. Otherwise, the international education hub would continue to remain no more than a slogan, while higher education is no more than a local knowledge activity which is falling behind in global knowledge.

(The writer is a Professor of Economics at the University of Colombo and can be reached at sirimal@econ.cmb.ac.lk).