The unknown de Alwises’ brush with Asian flora

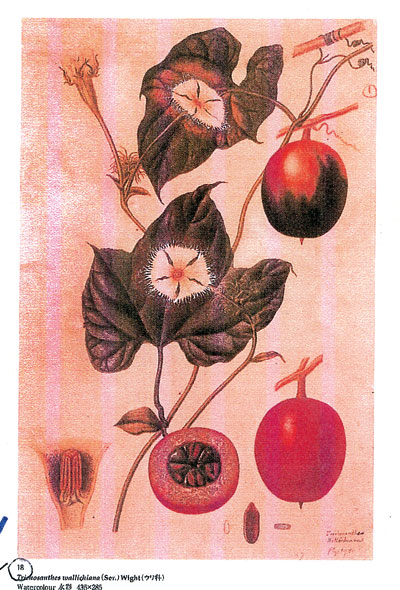

Botanical drawings of James de Alwis (above) and Charles de Alwis (left) done during their tenure as draughtsmen at the Singapore Herbarium between1890-1908 from ‘Botanical Illustrations of Singapore Botanic Gardens’

Singapore is the most unlikely place to look for paintings of botanical and natural history artists of Sri Lanka. But a chance meeting with Assistant Curator at the Herbarium of the Singapore Botanical Gardens Dr. Ruth Kew in 1998 led to a fruitful introduction to examine a series of wonderful drawings by the artists James and Charles de Alwis. Evocative of the rich tropical flora of Singapore and Malaysia, these finely delineated botanical drawings created for the Singapore Botanical Gardens have been languishing in the Herbarium Department for almost a century.

Although the exact relationship between the two artists has yet to be established, my conjectures were based on data generously supplied by Dr. Kew, Keeper of the Herbarium and Library.

At Dr. Kew’s request in January 1999, I contributed a brief biographical note, which appeared as a caption to an illustration in ‘Gardenwise’ – a newsletter and magazine published by the Singapore Botanic Gardens.

At long last in September 2002, the recognition much overdue to the de Alwis artists came in the form of an exhibition of botanical drawings loaned by the Singapore Botanical Gardens held at the Kochi Prefecture Botanic Gardens, Japan from September 15, 2002 through to February 23, 2003. The exhibition was titled “Welcome to the Flora Gardens of Asia.”

An extensively illustrated catalogue of this exhibition in Japan highlighted some of the best and the rarest illustrations of botanical specimens that were published to coincide with the event. Quite amazingly the majority of the plates published in the catalogue were selected from the botanical drawings of James de Alwis and Charles de Alwis done during their tenure as draughtsmen at the Herbarium between 1890-1908 and are illustrative of their consummate skill as natural history artists.

James was the first of the two artists to enrol at the Herbarium under Director, Dr. Henry Nicholas Ridley (1855-`1956). In his annual report of the Gardens and Forests in the Strait Settlement- 1890, Dr. Ridley commented:

“In March Mr De Alwis arrived from Ceylon and was employed out of the vote for the publication of the Malay Flora in making drawings of rare and more interesting plants of the Peninsula. He executed seventy highly finished and accurately coloured drawings.”

Ridley was the first scientific Director of the Singapore Botanical Garden in 1888, which was founded in 1859 and the Herbarium almost 16 years after the establishment of the main Gardens.

Among the field botanists of the tropical rainforest of the Malaysian region, Ridley was one of the most knowledgeable. Among colleagues who found him obstinate he was known as “Mad Ridley” or “Rubber Ridley”. But it was Ridley who introduced many new crops and plants economically beneficial to Singapore and Malaysia- including rubber for which he was ridiculed for his persistence in persuading coffee planters.

History proved him right when rubber became the most important crop in the Strait Settlements, as these countries were known when they were British colonies. Over the years Ridley collected thousands of specimens for the herbarium and which formed the basis for his five volume work- Flora of the Malay Peninsula (1922-1925). In it he published descriptions of hundreds of species of little known flora of this region. Many of these new species of plants were discovered and identified by Ridley during his field and research work. Many were drawn and documented for the first time by the two de Alwises.

By the end of 1909 as the work progressed, Ridley was keen to accumulate as much data as possible on the class Fungi of the tropical region. One of his specialities, very little was known to science of fungi at the beginning of the 20th century.

By 1891 the artists from Ceylon had covered much ground producing drawings for the Herbarium’s demands but also preparing illustrations for the lithographic plates for a planned publication including those of the rare Palms and Pandanus species of the flora of the Malay Peninsula.

By 1903 there were two more assistants recruited as artists and draughtsmen for the Herbarium. One was the unfortunate Indian artist D.N. Choudry who after a few months suffered increasingly from a brain disorder and was warded in the lunatic asylum in Singapore and as the situation deteriorated was later sent back home to India.

Charles de Alwis was the other artist recruited in November the same year. Both Charles and James may have migrated to Singapore in March 1890 but the former was working as a photographer at the Public Works Department and was seconded to the Herbarium on November 1, 1903. The annual report records indicate that Charles was active in the Singapore Botanical Gardens between 1903-1907.

Charles’s annual salary was stipulated Singapore $ 450. A further sum of S$ 216.65 was allocated to obtain art materials required for the work of the Drafting Department of the Singapore Gardens such as colours, brushes, rubbers (erasers).

There is little doubt in Ridley’s mind that both James and Charles were highly talented in delineating botanical subjects. Moreover Ridley was impressed with their output in producing these fine accurate drawings given the drawbacks of working in Singapore’s hot humid climate.

Ridley in his annual report of 1909 highlighted the problems artists illustrating fragile plant specimens had to undergo in such a hostile environment not conducive to work:

“The Artists continued in making drawings of important plants and towards the end of the year, in the rainy season a large series of drawings of soft Fungi, of which little or nothing is known and which are impossible to preserve in alcohol in this country so that coloured drawings are the only way of recording and identifying them satisfactorily. Of the few drawings sent to Kew these plants proved to be new to science. The artist also made a few supplementary lecture diagrams”.

Ridley in the 1900 annual report records that James de Alwis emigrated from Ceylon and in all probability Charles too did the same and they were in some way closely related.

It has been argued in published research material that both James and Charles de Alwis were probably direct descendants of Harmanis de Alwis Seneviratne (1792-1894), the patriarch of a dynasty of natural history artists. Harmanis de Alwis was born in the Southern coastal town of Kalutara.

His role in the history of the Botanical Garden in Sri Lanka was through his links with Alexander Moon and also in many ways to the very beginning of the history of the establishment of the Botanical Gardens network under the British.

In 1817, Moon succeeded William Kerr who died in 1814 as the Resident Superintendent of the Botanical Gardens after it was transferred from Slave Island to Kalutara. As far back as 1818 when the Gardens were in Kalutara, Harmanis de Alwis’s talent was recognised by Moon who recruited the young man as a draughtsman.

Moon continued to hold the post of the Superintendent of the Peradeniya Botanical Gardens when it was translocated from Kalutara to Peradeniya in 1821 and Harmanis de Alwis accompanied him.

By 1826, Harmanis was appointed as the Garden’s Botanical Artist and Draughtsman at a salary of 12 Pounds sterling, and held this post for 36 years, retiring when he was 70 years old.

He was to live up to 101 with all his faculties intact. During his time as the Senior Draughtsman of the Peradeniya Botanical Gardens and during his career he had delineated almost 2000 species of flora of the Island. In 1839 Robert Wright (1796-1872), the famous botanist of Indian flora invited Harmanis to travel to Chennai, Tamil Nadu, and work under his supervision to illustrate a wide range of publications, where he was trained to dissect and draw with the aid of a microscope.

Harmanis de Alwis Seneviratne drawn by an unknown artist

In 1831 Governor Barnes bestowed the title Muhandiram and later Governor Anderson honoured him with the title of Mudaliyar in 1854, for his valuable contribution. In the Peradeniya Botanical Gardens he was recognised for his skill both as an artist as well as identifying new species of plants – Harmanis was also a plant collector and enriched the Herbarium in the Gardens. By 1865 his son William was appointed as assistant and later succeeded his father to the post as the Head of the Drafting Department of the Peradeniya Gardens.

In 1902 William’s son succeeded him. In the course of his career William recorded almost 1000 species of fungi – most new to science. In 1874 William commenced illustrating the butterfly fauna, which finally culminated in the publication by Frederick Moore of a five-volume tome in 1880. Remarkably for the next half a century right up to the 1950s, the de Alwises dominated the field of illustration in natural history and virtually spanned five generations.

At least three or more of Harmanis’s sons continued to be associated with the Peradeniya Botanical Gardens, and Agricultural Department and continued to produce botanical illustrations. In the centenary publication of the Peradeniya Botanical Gardens (1921) four of William de Alwis’s sons are recorded working there in various capacities As late as 1951, almost a century and a half after Harmanis commenced his career another member of this famed family of botanical artists A.George de Alwis executed the illustrations for – A manual of the weeds of the major crops published by the Department of Agriculture.

Even as late as 1956 one of the other descendants of Harmanis- A.G. de Alwis worked on the illustrations for the Grasses of Ceylon by S.D.J.E. Seniviratne.

Of the 244 Botanical illustrations now lodged in the Archives of the Herbarium Singapore Botanical Gardens related to the work of James and Charles de Alwis passed on to me by Dr. Christina Soh(Curator Herbarium) in 2010 the following is the break down of the drawings related to the de Alwises. Charles de Alwis, 212 illustrations and James de Alwis had 18, and the balance four were a composite illustration by both artists.

This discrepancy and loss of drawings contradicts Ridley’s account as reported in his annual reports between 1890-1903. Before the Second World War Ridley transferred many specimens and drawings to Kew Gardens in London and only a part of this was later returned from London to Singapore, and as such no way reflects the total output of work of both Charles and James.

As Natural History artists the de Alwis family’s contribution to science in documenting the specimens both in the wild as well as in the laboratory is unparalleled.

The significant feature of this was not only that their documentation lasted over one and a half centuries but also had a wide geographical and ecological area coverage that included countries such as Sri Lanka, India, Singapore, Malaysia and a part of Indonesia. In the annals of natural history documentation, as far we are aware no such family grouping of Natural history illustrators has been recorded elsewhere in the world of science.

Dr. Rohan Pethiyagoda in his attractive and hugely informative publication Pearls, Spices and Green Gold, an illustrated history of biodiversity exploration in Sri Lanka [2007], has thoroughly researched the varied contribution to natural history illustration by this dynasty of artists. He has also published an array of articles on this subject.

My effort is to take these findings one step further and examine this arm of the de Alwis family, which had links to Singapore and Malaysia and their contribution to the study of the flora of South East Asia. Remarkable as it might have been, the de Alwis family never gained the recognition they deserved in their own native country.