Lord Buddha, the great physician who dispensed practical advice

View(s):By Bhante S. Dhammika of Australia

During the Buddha’s lifetime he was given numerous epithets in recognition of his outstanding qualities. Some of these include the Happy One, Teacher of Gods and Humans, Lord of Creatures, King of Truth, Teacher, etc. One of the most interesting of these epithets, found in the Itivuttaka and several other places, is Supreme Physician (Anuttaro Bhisakko).

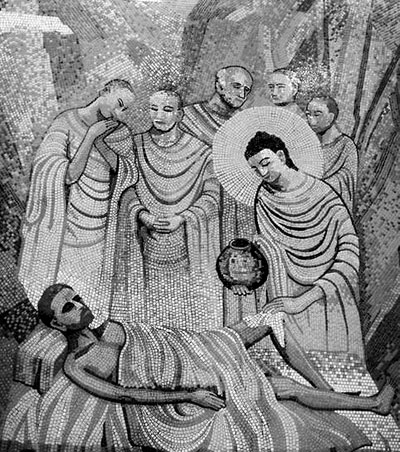

A modern painting depicting the Buddha attending to a sick monk

It is usually thought that this refers to the Buddha’s ability to soothe and ultimately heal the afflictions of samsara – hatred and greed, fear and longing, ignorance and selfishness. Certainly this is how the Paramatajotika understands it: “The Buddha is like a skilled physician in that he is able to heal the sickness of the defilements.” While this is a legitimate interpretation of the epithet, it is only part of the reason the Buddha was equated with and praised as a skilled and compassionate physician. He also had insightful and practical things to say about doctoring and nursing, sickness, healing and health in the conventional sense.

In the Dhammapada the Buddha said: “Health is the highest gain”, almost a platitude one might think, but also a statement that most people never give attention to until they become sick. As societies such as Sri Lanka become more prosperous and integrated into the consumer economy, new diseases start to appear – obesity, heart disease, high blood pressure, tooth and gum problems, etc. all having their origins in lack of exercise and over-consumption. The Buddha’s observation should be a reminder not to sacrifice the benefits of consumerism to poor health.

Just as there are different diseases patients can have different prognoses. On this matter the Buddha observed: “There are these three types of patients to be found in the world. There is the patient who, whether or not he obtains the proper diet, medicines and nursing, will not recover from his illness. Then there is the patient who, whether or not he obtains the proper diet, medicines, and nursing, will recover from his sickness anyway. Lastly there is the patient who will recover from his illness only if he gets the proper diet, medicines and nursing. It is for this last type of patient that proper diet, medicine and nursing should be prescribed, but the others should be looked after also.”

Apart from this being an astute and clear-eyed observation this also contains something of major importance; the Buddha’s last point. Susruta, the father of Indian medicine, advised the physician not to treat a patient who is likely to die so as to avoid being blamed for his or her death. In contrast, the Buddha said patients should be treated and nursed even if they were going to die. This is probably the earliest inkling of what today is called palliative care. There is no doubt that many of the ethical principles Susruta taught are of a high order, but on this point the Buddha’s were superior and ahead of their time.

Recognising that there can be a connection between the body and consciousness and thus that one’s mental state can be a factor in certain medical conditions, the Buddha said that this need not be inevitable and advised his disciples thus: “You should train yourself to think, ‘Though my body be sick my mind shall not be sick’.”

Contrary to popular misconception, the Buddha did not claim that all physical conditions, including injury and illnesses, were necessarily caused by past kamma, He mentioned at least eight causes of sickness of which only one was kamma; the others being an imbalance in the bile (pitta), in the phlegm (semha), the wind (vata), imbalance in a combination of all three (sannipata), seasonal changes (utuparinama), carelessness (visamaparihara) and external agencies (opakkamika, e.g. accidents). On other occasions he mentioned that improper diet and overeating can likewise cause sickness while intelligent eating habits can contribute to “freedom from sickness and affliction, health, strength and a comfortable living.”

As disease and sickness with non-kammic causes can be susceptible to medical intervention the Buddha saw the physician’s role as a vital one. Consequently the Buddha’s Dhamma is replete with information pertaining to medical ethics. The Buddha said: “Those who tend the sick are of great benefit (to others).” Because the Tipitaka predates the separation and specialization of the medical profession as presented in early ayurvedic treatises (Susurtasamita and Carakasamita) it rarely makes a distinction between the doctor (bhisakka, tikicchaka or vejja) and the nurse (gilanupaṭṭhaka). At the Buddha’s time the doctor probably performed all the functions in the sick room, including that of nursing the patient.

So the Buddha offered this advice to the physician/nurse: “Possessing five qualities, one who nurses the sick is fit to nurse the sick. What are the five? He can prepare the medicine; he knows what is good and what is not. What is good he offers, and what is not he does not; he nurses the sick out of love, not out of hope for gain; he is unmoved by excrement, urine, vomit and spittle; and from time to time, he can instruct, inspire, gladden and comfort the sick with talk on Dhamma.”

Of the five points mentioned here the first concern the physician’s responsibility to be fully trained in and skilful in the administration of drugs, given that the physician’s raison d’etre is effective healing and that some drugs can be dangerous if not prescribed properly. The second point is perhaps equivalent to the Hippocratic Oath’s third and fourth stipulation; that the physician shall never do anything to harm a patient, even if asked to do so. The third point counsels the physician to have a benevolent attitude to patients and put their welfare above his or her personal gain. The fourth point reminds the physician that at times it might be necessary to deal with the loathsome aspects of the human body and that he or she should do this with detachment, both for his or her own mental balance and so as not to embarrass or humiliate the patient. The fifth and final stipulation is a recognition of the fact that spiritual counselling and comfort can have a part to play in healing and that the physician needs to have at least some abilities in this area.

The Buddha did not just talk about ministering to the sick, on several occasions he did just that. In the most famous of these incidents he and Ananda washed and comforted a monk who had been neglected by his fellow monks and was lying in his own excrement; a horrible and humiliating situation to be in. After looking after this monk the Buddha called the other monks and in measured but firm words scolded them for their neglect of one of their fellows. “If you would minister me, minister the sick.” We do not know what influence this exhortation and the Buddha’s example had on the development of medical care in India and the lands where Buddhism spread, but we do know that they were long remembered and often quoted.

An important Mahayana work still popular in China, the Brahmajala Sutra (3rd cent. CE), says much the same thing: “If a disciple of the Buddha sees anyone who is sick, he should provide for that person’s needs as if he were making an offering to the Buddha.” 1700 years after the Buddha, the Sri Lankan author of the Saddhammopayana (12th century) wrote: “Nursing the sick was much praised by the Great Compassionate One and is it a wonder that he would do so? For the Sage sees the welfare of others as his own and thus, that he should act as a benefactor is no surprise. This is why attending to the sick has been praised by the Buddha. One practising great virtue should have loving concern for others.” But apart from the Buddha and Ananda ministering to the needs of the sick and neglected monk there are at least half a dozen other incidents in the Tipitaka where the Buddha visited sick and ailing patients “out of compassion” and counselled them. In each case the patient is said to have either improved or recovered.

The Buddha was aware that while medical intervention is crucial for the restoration of health, the patient’s attitude also has a part to play. And the Buddha had something to say about this. In the Anguttara Nikaya he said:“Possessed of five qualities, a sick person is of much help to himself. What five? He knows what medicine is good for him, he knows the right measure in his treatment, he takes the medicine as prescribed, he describes his illness to the nurse who cares for him out of kindness, saying, ‘It comes like this.’ ‘It goes like this.’ ‘When it is there it is like this’; and he endures the various pains of the sickness.” Again, this is practical, common sense advice.

When it comes to the combination of sickness and religion, healing is often associated with miracles. Many great religious leaders are credited with having been able to heal medical afflictions miraculously. Whether such claims are true is hard to say. Certainly the claims of modern faith healers have all too often proved to have been fraudulent, today’s so-called ‘televangelists’ in America being a good example of this. And careful scientific study of faith healing over the last decades has so far produced very little evidence of its validity. Whatever the case, there is no incident in the Tipitaka of the Buddha or any of his disciples healing someone through miraculous means, or having claimed to have done so. This tells us something interesting about the Buddha’s understanding of causes and cures of disease and something about the general character of his Dhamma as well.