Scholarly work that fills void in Sri Lankan biographical landscape

View(s): I have always regretted the dearth of biographies of major public figures in Sri Lanka. Of our principal national figures D.S. Senanayake, S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike and J.R. Jayewardene have had biographies good (in the case of D.S. Senanayake and J.R. Jayewardene), bad and indifferent (in the case of Bandaranaike), but no biography so far of Mrs Bandaranaike who had a longer spell as head of government than her husband.

I have always regretted the dearth of biographies of major public figures in Sri Lanka. Of our principal national figures D.S. Senanayake, S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike and J.R. Jayewardene have had biographies good (in the case of D.S. Senanayake and J.R. Jayewardene), bad and indifferent (in the case of Bandaranaike), but no biography so far of Mrs Bandaranaike who had a longer spell as head of government than her husband.

Politicians, even statesmen, are not the only public figures deserving of a biography. I can think of at least two who are not politicians, who deserve a comprehensive biography. If one needs to think of a family and not an individual one could be that of C. Don Bastians’s, De Soysa Charithaya (in Sinhala) published as long ago as 1904 of the de Soysa family, which means we are in need of a volume that attempts a fresh look at the Soysa family or better still a look at the founder of the de Soysa family fortunes. While a fresh look at the family is urgently needed for the reason that it would inevitably lead to a biography of the founder of the family. That would emphasise the point that my preference would not be family but of individuals and of a group who thrived in Sri Lanka’s coffee era and the coffee enterprise—one of the finest in the world of the day—and escaped the shattering efforts of the collapse of the coffee industry which saw the end of the several British enterprises. The de Soysas not only survived it but far better still thrived so well that their descendants have thrived as well almost to the present day.

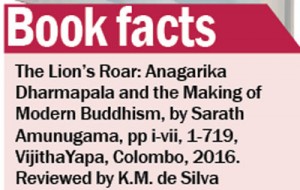

So much for the de Soysas, we need to turn our attention to the only other ‘non-political’ public figure in Sri Lanka’s recent history that deserves a comprehensive biography—Anagarika Dharmapala (1864-1933) born to the Hewavitharanes, a very wealthy family. Sarath Amunugama fills this gap in Sri Lankan biographical landscape with a path-breaking volume that leaves Sri Lanka’s world of scholarship very much in his debt. There has been no other study of this historic figure;indeed one cannot think of a similar volume much less refer to it as something as good as Amunugama’s.

Anagarika Dharmapala was an unusual case of a child born to a cross-caste marriage between the goyigama (the goyigama elite) the highest in the Sinhalese caste hierarchy and the durava, a small but powerful non-goyigama caste group from the Sri Lanka littoral. Dharmapala, as Amunugama shows, always emphasised the goyigama part of this heritage. He—Dharmapala—would have liked to ignore the durava part of his heritage but he could not do so. The duravas would not let him do that. They felt cheated. There was no need to treat them as being in anyway inferior to the goyigamas and in any case they refused to acknowledge any inferiority to the goyigama in their caste rivalries.

Among the problems that faced authors of any serious study of the life and times of Anagarika Dharmapala was that one had to be as familiar with the Indian background to Dharmapala’s career as a public figure, as much as his Sri Lankan roots—or rather his involvement in the recovery of Buddhism in Sri Lanka in particular and in South Asia as a whole. Much, if not most, of his adult life in the cause of Buddhism and of Buddhist recovery (in Sri Lanka) was spent in India, Bengal in particular. At the time he began his work in India, Calcutta (now Kolkotta) was the capital of the British raj, and Bengal the heart and soul of it. By the time he died or was in his physical decline the capital of the raj had long since moved to Delhi, while the Bengali (and later the Bangladesh elite)—the Bhadralok he admired so much—had been left behind in the maturing nationalist movement that was shaking the British raj. To the end of his days Dharmapala regarded himself as very much a Sri Lankan or a Sinhalese bharatlok. He was way ahead of the Sri Lankan and Indian nationalists in insisting which the goal of the South Asian nationalist movement was purnaswaraj. In this he was way ahead of the nationalists of his day in India (or Bengal) and Sri Lanka. When in the course of time—after Dharmapala’s death—independence came to South and South East Asia—only Burma stood for purnaswaraj and succeeded in securing that objective. All the others, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh were satisfied with independence within the Commonwealth of Nations in the post- British raj scheme of things.

An early convert to Theosophy led by Blavatsky and Olcott, his non-commitment to Buddhist Theology took him to the Theosophical movement’s headquarters in Adyar and from there to the recovery of the Buddhist places in British India. In the last decades of his life, the recovery of the Buddhist sites became one of principal objectives of his life;in particular to save Buddhagaya from the control of the Hindu Mahants. This was something he could not achieve in his life time, but he had led the way and his success in the historic processes of Buddhist recovery succeeded in establishing Buddhism as a civilizational influence internationally. For instance his creation, the Mahabodhi was the main facilitator of Ambedhkar’s decision to convert to Buddhism with the millions of his caste fellows, the Dalits.

Sarath Amunugama, himself a blend of Sri Lankan (the University of Ceylon at Peradeniya and later the University of Peradeniya) and School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences (the École des Hautes études en Sciences Sociales in Paris), has made a major contribution to the Asian academic enterprise in the field of biography. As a member of Sri Lanka’s bureaucracy he reminds us of one of the less known but important achievements of colonial rule—bureaucrats as scholars. His work is an effort at the preservation of that tradition and its extension to the field of national politics, a renewal of a tradition that featured men like Sir Paul Pieris and Dr Colvin R. de Silva.

(K.M. de Silva was professor of History at the University of Ceylon—University of Peradeniya—and currently a Director of the International Centre for Ethnic Studies Kandy/Colombo, Sri Lanka).