Columns

Government’s first year political achievements and economic disappointments

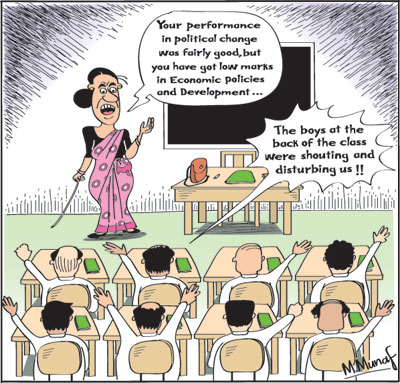

View(s):Assessments of the new government that came to power a little over a year ago have been mostly those of disappointment and disillusionment. However a balanced assessment of the first year’s performance is that there have been considerable improvements in political freedoms and governance, but inadequate achievements on the economic front. The disappointment of its economic performance is quite widespread.

Reasons

Reasons

Several underlying reasons account for this dissatisfaction. Those who supported and worked to overthrow the previous regime had high expectations. The actual achievements fall far short of these. Internal contradictions within the coalition and the split faction of the UPFA calling themselves the joint opposition have tempered the government’s reform policies. Their continuous opposition has been a severe distraction.

The government’s policies have to be implemented within a conspiratorial political scaffold. Despite these limitations there have been significant achievements in the democratisation of the country and the achievement of the rule of law. Yet many of the government’s actions fall far short of the laudable ideals of President Maithripala Sirisena’s statements and expectations generated by the political change.

Confusion and uncertainty

In contrast to the political achievements, there is considerable disappointment, confusion and uncertainty as to where the economy is heading. The persistence with bad economic policies, prevarication in the adoption of needed economic policies, the gulf between economic statements and actual policies, inability to implement policies and an inability to take bold decisions needed to resolve the economic crisis, have been reasons for the disillusionment with the government’s economic policies and doubts about its ability to steer the country from her current multidimensional economic crises.

Political freedoms

Political freedoms

A quantum leap in democratic governance is the main achievement of the unity government. There is no fear of abductions; there is freedom of expression; there is liberty to protest; and above all there is law and order and the rule of law. These are substantial achievements of a government that came into power though the people’s ballot and not by a violent overthrow of the government. This is not to deny inadequacies, limitations and violations of some principles of good governance. But the return to democratic freedoms is indisputable.

There are instances of nepotism, bad appointments to public office, suspicion of corruption, inept administration and delays in the administration of justice. Despite these and other limitations there is a huge difference in freedom and law and order in the country now in comparison to what prevailed during the last regime. The government is no longer meting out arbitrary punishments, there are no missing persons and for most part the rule of law prevails.

Institutional changes

There have also been significant institutional changes with the appointment of an independent Public Services Commission, Judicial Services Commission, the Right to Information Act and opening of an Office of Missing Persons (OMP). These are not incremental changes in the polity: they are reversals of a polity that was heading towards a dictatorship.

Economic front

In contrast, the story with respect to the economy is a sorry one. The inability to act in a decisive manner in the interests of the economy characterised the seven months since January 8th when the new government was instituted under President Sirisena and the past year. The economic policies pursued were understandable in political terms but disastrous for the economy. The interim budget of the new government aggravated the deep seated crisis they had inherited.

The interim budget of January 2015 envisaged bringing down the fiscal deficit from 5.7 per cent of GDP to 4.4 per cent of GDP however it ended up as one with one of the highest fiscal deficits in recent times to reach 7.4 per cent of GDP. Bringing down the fiscal deficit to around 5 per cent remains a serious challenge to the government.

The 2015 trade deficit reached US$ 8.4 billion and there was erosion in the foreign reserves in both 2015 and the early part of 2016. Bringing down the trade deficit to about US$ 7.5 remains the other serious challenge. Recent policy changes such as the depreciation of the currency, increase in interest rates and some tariff reforms are showing signs of impacting favourably on the trade balance. Earnings from tourism and other services earnings could result in a current account balance of payments surplus to the tune of about US1.5 billion. Yet the huge debt servicing commitments this year means that further foreign borrowings are need.

Legacy and policies

While much of this crisis was owing to the legacy of huge foreign debt servicing costs, bad economic policies adopted by this government, lack of confidence in the economic policies, as well as inept administration and unsatisfactory economic management resulted in an aggravation of the financial crisis and a lack of confidence in the government’s economic management.

A clear instance of unsatisfactory management was the reversal of the policies enunciated in the Prime Minister’s Economic Statement of early November in the budget later in the month. The government’s November 2015 budget became virtually a non event with continuous revisions and changes.

The political context

As this column has pointed out earlier the root of the problem of economic policy making lies in the country’s political environment and culture. Implementing correct economic policies in Sri Lanka’s political context and culture has proven immensely difficult.

The recent uproar over the increase in VAT is a dramatic illustration of the problem. Good economic policies are difficult to pursue owing to the prevailing political culture.

Balancing political and economic dynamics will always be a decisive factor and pursuing right economic policies are difficult in a country where the government has to appease the multitude. Pragmatic and realistic economic reforms are a vain hope in the political context and culture of the country.

The serious implication of this is that the country’s prospect of rapid economic development is unrealistic, even though some economic strides are possible especially if global conditions turn favourable. In the foreseeable future the country is likely to progress hemin hemin. At best we may be able to hasten slowly.

Leave a Reply

Post Comment