Columns

Mother Teresa at Heaven’s Gate

View(s):Santa Clause never came to Mother Teresa’s door. Instead it was cholera, smallpox, leprosy and a whole host of other terminal illnesses sardine packed in a container of human cargo that tottered to her door quivering betwixt ebbing life and painful death.

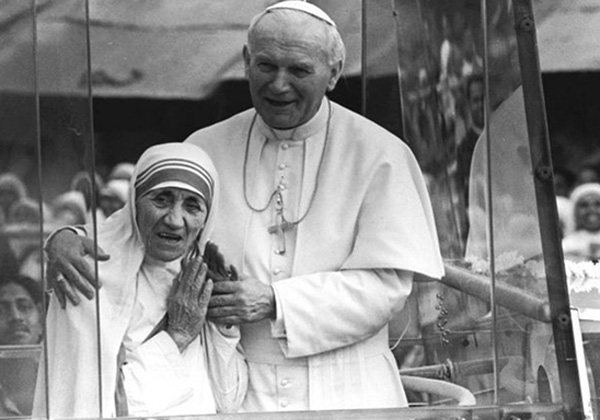

MOTHER TERESA:. "When the call within the call came to leave the convent and help the poor and live amongst them, it was an order." The Blessed Theresa with Pope John Paul II in the Popemobile outside the Home of the Dying in Calcutta

They came not for miracles but for succour; for relief, care and a prayer only she could provide them at the home of her Mission of Charity in the Black Hole that was India’s Calcutta. For them and for the thousands who were inspired by the selfless dedication of the woman who had bedecked herself in the poverty of the cross, she became a saint in life. Now 18 years after her death at the age of 87, and 12 years after being beatified as the Blessed Theresa of Calcutta, the Vatican announced this week that she will be immortalised in the canon of saints when Pope Francis bestows upon her the Roman Catholic Church’s highest honour: sainthood.

Beatification is the last stop before the Holy See officially recognises the Blessed One is officially installed in Heaven as a saint. Though no date has been officially announced yet, it is widely believed that the Blessed Teresa will be canonised on September 5 next year, the day of her 19th death anniversary. Thereafter, Catholics the world over can venerate and pray to her as a saint fit for public worship. The saint, once gloried in heaven, is assigned a feast day when the faithful can freely celebrate and honour him or her without restraint.

Generally the process of canonisation moves at the speed of continental drift. A person must have acquired a ‘fame of martyrdom’ or a ‘fame of sanctity’. The Bishop of the Diocese will commence an investigation whether any miracle was wrought by the candidate’s intercession. The investigation will also focus on the person’s writings to determine whether it possesses ‘purity of faith’. Once the report is complete it will be submitted to the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints. A ‘Devil’s Advocate’ will then be called upon to raise objections and doubts which must first be resolved. Once the first miracle has been established, the next step is beatification. After this has been done, another miracle must be confirmed for the church to canonise the candidate.

This process can take decades, even centuries, for the Vatican to confirm without doubt the miracles purported to have been wrought by potential aspirants to sainthood. For instance, in the case of Father Vaz it took 304 years after his death for the Vatican to make him a saint when Pope Francis canonised him on January 14 this year in Colombo.

For Mother Teresa, however, it happened in double quick time. It was helped, in no small a measure, by Pope John Paul II who paved the way to expedite the long drawn process; and, unwittingly perhaps, realised his own beatification six years after his death.

For Mother Teresa, however, it happened in double quick time. It was helped, in no small a measure, by Pope John Paul II who paved the way to expedite the long drawn process; and, unwittingly perhaps, realised his own beatification six years after his death.

First in 1983, John Paul II abolished the 400-year-old office of the ‘Devil’s Advocate’ also called “Promoter of the Faith’, whose role it was to argue against the canonisation of the proposed candidate by adopting a sceptical view of the candidate’s character. He was entrusted with the duty of questioning the evidence. He had an official responsibility to argue that the miracles attributed to the candidate were fraudulent. With the office of the Devil’s Advocate abolished, there was none to show the other side of the coin, none to put a spoiler and delay the investigation.

Secondly Pope John Paul II also removed the rule that prevented the process from commencing until five years of the candidate’s death had passed. Thus fast tracked for sainthood, Mother Teresa was beatified six years after her death.

This was when her first miracle as required for beatification was accepted by Pope John Paul II as authentic. It concerned the curing of an Indian woman who was said to have been suffering from an abdominal tumour. The Pope held it as a result of a supernatural intervention of Mother Teresa. The Indian woman, Monica Besra was supposedly cured when a locket containing Mother Teresa’s photograph was placed on her stomach. Indian doctors and rationalists, however, rushed to denounce it as bogus, claiming that Monica Besra had responded to medical treatment in government hospitals rather than to any miraculous intercession. But the Pope decreed it as a miracle. And the Pope is infallible. Beatification swiftly followed.

The second miracle concerned the case of a Brazilian man suffering from a viral brain infection. According to Father Brian Kolodiejchiuk, the missionary promoting Mother Teresa’s canonisation, the unidentified man was in a coma and was in danger of dying in December 2008 due to the build up of fluid in his brain. He was about to undergo an emergency operation when a neurosurgeon came to the operating room and found the patient inexplicably awake and without pain. At the moment the surgery was due to take place, the man’s wife was at church praying with the pastor beseeching Mother Theresa to intercede and save her husband.

Since becoming Pope, Francis created six new saints in 2014 – two Indians and four Italians – praising their “creative” commitment to helping the poor. Since he began his reign two years ago he has created 26 saints in all. Mother Teresa will probably be number 27.

But though Mother Teresa’s ascent to be enthroned in heaven as saint has been unduly swift, each steep step has teemed with critics. But which saint didn’t have a brigand of sinners to storm the idol and dull the worship? For every saint the world spawned, thousands of iconoclasts were at hand to denigrate earthly divinity.

Foremost amongst Mother Teresa’s attackers was Christopher Hitchens, who, upon her beatification six years after her death, attacked the very basis of her motivation. Though the office of the Devil’s Advocate had been abolished, Hitchens was called to address the Congregation of the Cause of Saints as a witness. He recalled meeting her and said, “I met her. My impression was that she was a woman of profound faith, at least in the sense that one can say of anyone, who is a completely narrow-focused single-minded fanatic. She assured me that she wasn’t working to alleviate poverty. She was working to expand the number of Catholics. She said, ‘I’m not a social worker. I don’t do it for this reason. I do it for Christ. I do it for the church.” The Congregation, however, decided that his arguments were irrelevant and dismissed him.

The main accusation was that she used the poverty of the poor to proselytise. And that India’s millions living in poverty and sickness were soft target for her evangelism. That she found in Calcutta’s slums, the fertile nursery of “the unwanted, the unloved, the uncared for” ready, due to their wretched circumstances, to barter their diverse faiths for a mess of Christian pottage.

The British medical magazine Lancet criticised the care in Mother Teresa’s facilities in 1994, and an academic Canadian study faulted “her rather dubious way of caring for the sick, her questionable political contacts, her suspicious management of the enormous sums of money she received, and her overly dogmatic views regarding, in particular, abortion, contraception, and divorce.”

But through it all, the Holy Father Pope John Paul II’s faith in her remained unshaken and he was amazed how this frail Albanian women clad in a simple white cotton sari with a blue border found the inner strength to bear her cross and asked: “Where did Mother Teresa find the strength and perseverance to place herself completely at the service of others? She found it in prayer and in the silent contemplation of Jesus Christ, his Holy Face, his Sacred Heart.”

She was born in Macedonia to an Albanian family and was baptised as Anjezë Gonxhe Bojaxhiu or rosebud. According to her biographer, she became committed to a religious life and, at the age of 18, renounced her lay life to join the Sisters of Loreto in Ireland. There she determined to become a missionary. In 1929 she set sail for India and upon arrival began her novitiate at Darjeeling, near the Himalayas. Here she taught at St. Theresa’s School. When she took her vows as a nun in 1937 she chose to be named Teresa, after Thérèse de Lisieux, the patron saint of missionaries.

The call within the call came to her on September 10, 1946 when she was travelling by train to Darjeeling from Calcutta for her annual retreat. She said, “I was to leave the convent and help the poor while living among them. It was an order. To fail would have been to break the faith.”

She did not break the faith. Nor did she fail. She received permission from the Vatican to start the Missionaries of Charities. Her mission was to serve “the hungry, the naked, the homeless, the crippled, the blind, the lepers, all those people who feel unwanted, unloved, uncared for throughout society, people that have become a burden to the society and are shunned by everyone.”

What began as a small group of 13 nuns in 1950 had, at the time of her death 47 years later, expanded to a massive religious institution with more than 4,000 sisters in over 500 missions worldwide operating orphanages, AIDS hospices and charity centres worldwide, and caring for refugees, the blind, disabled, aged, alcoholics, the poor and homeless, and victims of floods, epidemics, and famine. In 1979, she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, “for work undertaken in the struggle to overcome poverty and distress, which also constitutes a threat to peace.”

Whatever her detractors may say, Mother Teresa was a saint in life. The wretched thousands, the unwanted, unloved, uncared who passed through her door will vouch for that. As for the two miracles needed to make her a saint in death, it hardly matters whether the miracles were genuine or were a charade. Mother Teresa needed no external miracles to prove her saintly credentials. That was the stuff for wandering fakirs to demonstrate. The moving spirit that inspired her and drove her to dedicate her life to the welfare of the misérables of humanity the world shunned was the only miracle that was required. The miracle lay in her. Mother Teresa was the miracle.

Leave a Reply

Post Comment