News

Fear and suspicion dog EPF-ETF merger

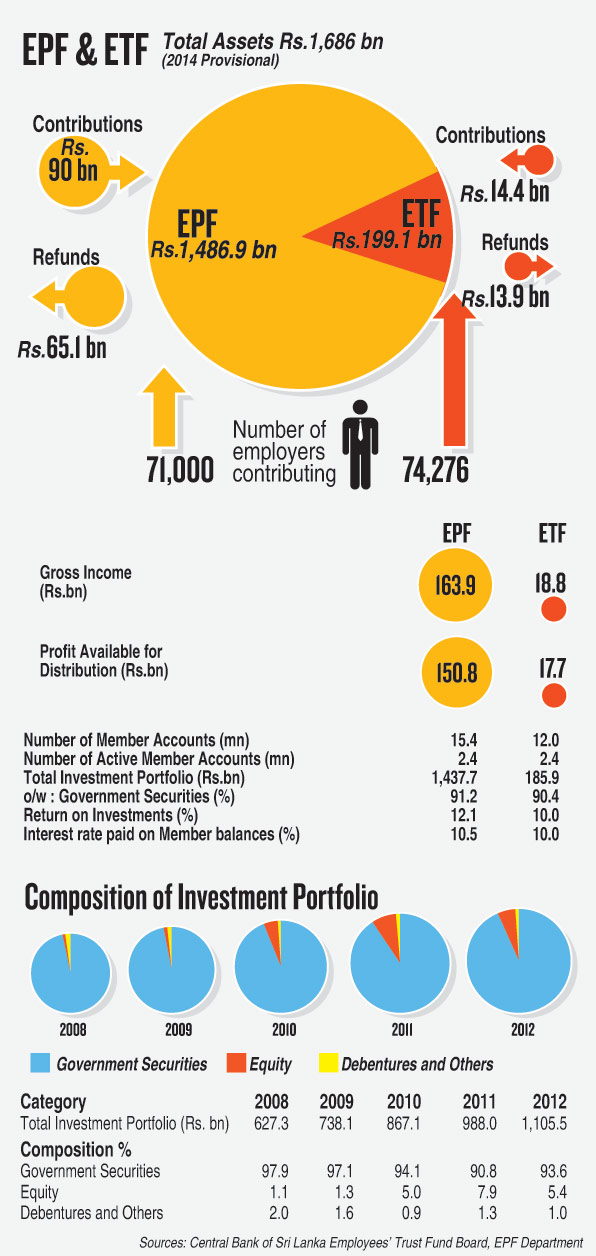

Plans to remove the Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF) from the Central Bank’s control and to merge it with the Employees’ Trust Fund (ETF) could fail over a lack of public faith in the Government’s motives.

The move — which has been tried and abandoned by previous administrations — is heavily dependent upon beneficiaries of the two funds accepting any alternative that is proposed. But the overriding fear is that the Government is either bowing to the dictates of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or plotting to dip into the workers’ kitty.

The IMF has plainly held that the EPF governance structure needs changing. In 2007, the IMF said the EPF must develop a “sound, robust, and independent governance structure with the clear objective of seeking the best investment returns for members, while taking into account reasonable levels of risk tolerance and the individual preferences and circumstances of workers”.

In 2013, it called for a “robust supervisory and governance framework for all pension funds, including the EPF”.

The Government now says the same. And it proposes to combine the EPF and the ETF into a giant National Pension Gratuity Fund (NPGF).

This will likely be managed by a Public Wealth Trust comprising trade union and employer representatives; Treasury and Central Bank nominees; two members nominated by the Constitutional Council; two others chosen jointly by the Prime Minister and Leader of the Opposition; and a Chairman and an Executive Officer.

The possible composition of the Trust was divulged to trade unions by Harsha de Silva, the then Deputy Minister of Policy Planning and Economic Development, as far back as August.

Recently, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe called a meeting of the National Labour Advisory Council (NLAC) — which has both trade union and employer representatives — to clarify the plans.

Linus Jayatilake, President of the United Federation of Labour, was among the attendees.

“It is not yet a written proposal,” Mr. Jayatilake said, adding that, “We are not agreeable to an amalgamation of the two funds. We also told the Prime Minister that we opposed the removal of the EPF from Central Bank supervision.”

There was consensus among worker unions on those points, although they did not rule out the idea of old age insurance. They stressed the importance of consultation.

And they pointed out that the previous Government’s attempt to introduce a private sector pension fund had failed because it had been done arbitrarily.

The Prime Minister gave ear and “seemed reasonable”. He said there was no rush. A committee is to be set up to further evaluate the proposal.

He maintained that EPF monies were mishandled in recent years and invested according to the whims and fancies of certain officials and politicians. There had been corruption.

“We have to discuss this from the point of view of the beneficiaries,” Mr. Jayatilake said. The main impediment is fear. Fear that shifting the EPF out of the Central Bank’s control will open the floodgates to abuse.

Fear that, somehow, the workers’ monies will be badly invested, frittered away or “stolen”. And concern that benefits will be lost.

Unions such as the powerful Ceylon Bank Employees’ Union (CBEU) have already started public awareness campaigns. They hope to drum up a united front against the proposal.

At present, the power of investing EPF monies lies with the Monetary Board of Sri Lanka (which governs the Central Bank) through the Labour Department. Ninety percent of funds must be in Government securities, which carry the lowest risk.

Keshara Kottegoda, an Executive Committee member of the CBEU, said priority must be given to security rather than returns. He did not think restructuring will guarantee that. “The Government says the Public Wealth Trust will be ‘accountable’ to Parliament,” he reflected. “That word is being used to fool the people.”

“The COPE (Committee on Public Enterprises) is accountable to Parliament and comprises Government and Opposition members,” he said. “There have been big media shows but not a single rupee has been recovered from the thieves identified by the COPE.”

There are worries that trade unions represented on the Public Wealth Trust will be partial to the ruling regime and let the monies be invested the way a Government wants.

There are fears that professional fund managers, who are few and far between in Sri Lanka, will have to be hired. The workers lose a percentage of the fund — which works out to a soaring amount — as fees and a third party gains.

Unions also fear that the Government will eventually adopt the IMF’s 2008 recommendation to divide the NPGF into four and assign each to a private fund manager. This, they warn, will be the second stage of the restructuring — the hidden objective.

Chandra Jayaratne, former Chairman of the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce, observed that the Government envisaged doing three things at the same time: joining the two funds together; formulating an administrative structure; and setting up a pension scheme.

The amalgamation would alleviate the cost of running two funds. But management will be complicated as the EPF was withdrawn at retirement while the ETF could be taken out at various times.

“Some of the benefits may have to be given up as a consequence,” Mr. Jayaratne warned. “For instance, will you allow employees to continue to withdraw the ETF and, if so, what portion would it be? Will there continue to be housing loan schemes and how will you manage those? Combining the two could make matters worse because of the mishmash.”

Management of the pool of investments also mattered. “When you try to farm out fund management to different people, you will create competiveness and better options,” Mr. Jayaratne said.

“But the integrity of the people managing the fund, oversight over them, the regulatory framework and enforcement are vital. If you have a regulatory structure but ineffective enforcement, will problems of the past happen?”

It was crucial for the public to realise that there were positives and negatives. If the stakeholders were not flexible, the Government will find it difficult to meet expectations.

Even longtime private sector managers like Sunil Wijesinha, a former ETF chairman, questioned the wisdom of merging the EPF and the ETF together.

“No,” Mr. Wijesinha replied, when asked whether he thought it was a good idea. It was tried twice in the early 1990s and 2000s but did not go through.

“Both times, I found that people were not clear about the objectives,” he said. “If the goal is to ensure the monies are invested properly what matters is not whether you have one or two funds, but that the Board is independent.”

A pension fund must be preceded by an actuarial study — one that compiles and analyses statistics to calculate insurance risks and premiums. Several analysts echoed this concern.

It is also clear that the Government has not done adequate research on whether employees prefer a pension scheme to a lump sum payment.

Mr. Wijesinha said he saw “absolutely no advantage of amalgamating” EPF and ETF. He also pointed to practical challenges. How will monies credited to individual accounts (as they are now), with interest and dividends credited at the end of the year to each account, be merged into one?

| No pump and dump games: Harsha Given the choice, most people would prefer a pension, said Deputy Foreign Minister and Economist Harsha de Silva. That is the foremost reason for thousands of employable men and women continuing to seek public sector jobs. Dr. de Silva was present at Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe’s meeting with the National Labour Advisory Council (NLAC). He is closely aware of the Government’s proposal to combine the EPF and ETF and to set up a pension scheme. He stressed, however, that “We are not even close to having anything on paper yet.” The Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF) was a unique animal, he said. It had two bosses—the Monetary Board of Sri Lanka and the Department of Labour. The Employees’ Trust Fund was different. It was managed independently, and not by the Central Bank. There was a conflict of interest that needed to be considered. “The Government started to make budget deficits,” Minister de Silva said. “When they continued to grow, the Government used its authority to get money from captive sources, the biggest of which was the EPF.” “To make matters worse, the Central Bank had two departments,” he elaborated. “One was the Public Debt Department responsible to borrow for the Government at the lowest possible rate. But it also had the EPF which was supposed to get the highest returns for the Fund for workers.” What happened was obvious. “The Government started to borrow from the EPF at low rates,” the Minister continued. “This happened over and over again. More and more people have written about this, not at a political level. This is the first time it is getting discussed like this.” Worker interests were getting pushed aside, he said. More than 90 per cent of EPF funds were leant to the Government. The fund had grown to be massive. At the end of 2014, it was Rs. 1.486 trillion (or Rs.1,486 billion). After 2009, the EPF was implicated in stock market “pump and dump” games. It became known as the buyer of last resort. Around this time, there was written representations regarding conflict of interest — how it was problematic for workers for borrower and lender to be one. The fund also saw negative returns in terms of inflation. “We were getting positive rates as nominal interest, but inflation was also high,” Minister de Silva said. “There were fundamental yet absolutely necessary reforms in the way this country is run.” Most workers, given the chance, would prefer a combination of lump sum payment and a pension, he believed. Dishing out thousands of Government jobs was not sustainable. Meeting employee aspirations for a pension was. “The solution is to have a pension for everyone,” he concluded. There are many issues to be tackled — such as how such a pension would be created. “Trade unions seem to be worried that, if the EPF is taken out of the Central Bank and amalgamated with the ETF, the safety of the money will be at stake,” the Minister acknowledged. “These are justifiable concerns. What the Prime Minister said is there is no hurry, no rush. We are seeking the views of trade unions to structure it in the best possible way.” |