News

High five for a tiny survivor

View(s):Tiny deer once thought to have been lost to Sri Lanka forever have a toehold on existence with the birth of a fifth baby to a small group kept under protection.

Born free: A hogdeer in Honduwa

The deer live on an island sanctuary in the Lunuganga set up two years ago by the Wildlife Conservation Society of Galle (WCSG).

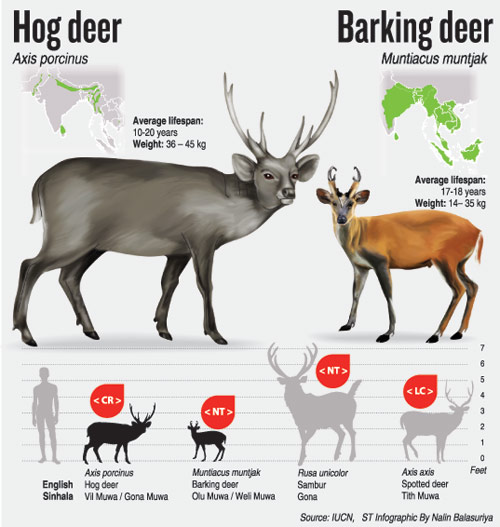

Known as vil muwa or gona muwa in Sinhala, hog deer (Axis porcinus) is identified as a “critically endangered” species by the National Redlist of Threatened Flora and Fauna.

In 2013, the WCSG set up an area on the island of Honduwa in the Lunuganga to raise hog deer in wild conditions as the first step in a long-term conservation program to ensure the species’ survival in Sri Lanka. Eight deer, five female and three male, live in this three-acre haven.

All but one of a previous litter died of weakness due to premature birth.

WCSG President Madura de Silva said all the hog deer at the Honduwa sanctuary are animals that had been handed over to the WCSG’s Wild Animal Rescue Centre at Hiyare at Galle.

He explained their sad history: “Many hog deer are hit by speeding vehicles while others suffer injuries due to attacks by predators such as feral dogs and water monitors.

We try to release the adult animals in the vicinity where they are found but baby hog deer, which have to be hand-fed, cannot be released back to the wild. The first generation of the Honduwa herd consists of such rescued animals.”

The species was believed to have become extinct until a few animals were spotted some decades ago.

There are four species of deer in the country: spotted deer, sambhur, barking deer and hog deer. Unlike the others, the hog deer is believed to have been introduced to Sri Lanka.

The animal is not even found in South India, so one theory is that ancestors of this deer might have been accidentally or deliberately unloaded when Galle harbour was used as a transit point in early colonial times.

Hog deer are found mainly in the Elpitiya, Balapitiya areas around Galle.

The animal prefers scrub jungles closer to marshy habitat and has also adapted to living in the cinnamon estates spread around the area.

Its relationship with cinnamon farmers is not cordial as it eats the tender parts of the cinnamon plant. As cinnamon plantations do not have the kind of undergrowth found in jungles the little deer, which stand just 60-70cm tall at the shoulder, can be easily spotted by predators.

Habitat loss is the hog deer’s main threat. The young are easy prey to dogs and water monitors (kabaragoya).

The first two weeks after birth is critical for baby hog deer as they are particularly vulnerable to predators. Female hog deer keep their new-born hidden in the tall grasses that grow around marshy land.

The two hog deer first brought to the Lunuganga sanctuary in 2013 had been attacked by water monitors in separate incidents and treated at the Hiyare rescue centre before being taken to the island sanctuary.

They had been only a few weeks old when found injured; one had a fractured leg. The baby animals were first bottle-fed and then hand-fed with grass and plant shoots.

Although their parents are hand-raised, the newborn fawn in the Honduwa sanctuary will be kept wild as much as possible without human interaction.

Mr. de Silva revealed that the WCSG is trying to obtain an area belonging to the Agriculture Department in the hog deer habitat declared as a larger protected area into which wild hog deer can be can released.

Such a reintroduction program cannot be carried out in a haphazard way, he said, adding: “If we get an opportunity to release these second-generation hog deer to be living free in the wild we might first release a couple with radio collars and monitor their movements to make sure of their survival”.

The hog deer rehabilitation and rescue programme began in 2009 at the Hiyare Wildlife Rescue facility, with support from the Nations Trust Bank. The island of Honduwa is under the guardianship of the Geoffrey Bawa Trust which is collaborating with the WCSG in this project, which is being supervised by the Department of Wildlife Conservation.

Michael Daniel of the Bawa Trust said the island is safe for hog deer. “There is no chance that feral dogs will infiltrate the island,” he said. “The facility is also fenced in order to keep the other predators at away.”

Mr. Daniel said the hog deer in the facility are monitored but their guardians “keep their distance in order to make the second generation wild as much as possible”.

-M.R.

| Barking deer too need protection Two barking deer kept caged in poor conditions were discovered by authorities in the past fortnight. One person in Avissawella was taken into custody. The other deer was found at Madolsima in Badulla, living in a very small cage and in unhygienic conditions. Barking deer (Muntiacus muntjak, known as weli muwa or olu muwa in Sinhala), are widespread in Sri Lankan jungles, commonly in the lower hills. Like the hog deer they are small and do not, like the larger deer species, roam in herds but in pairs or alone. They prefer open area on the edges of forest. The deer’s call resembles a bark, usually sounded to indicate the presence of a predator. Barking deer are found in Bangladesh, China, India, Nepal, Pakistan and several countries in south-east Asia and are listed as “near-threatened” by the National Redlist of Threatened Fauna. |