A balancing act

Prof. Tariq Ramadan’s visit to Sri Lanka is curiously timely. Fifty years ago to the very day he was delivering the M.A. Bakeer Markar commemorative lecture (September 21), Bakeer Marker – late Speaker of the Parliament of Sri Lanka, spoke up in favour of Said Ramadan, Tariq Ramadan’s father, in response to questions raised in Parliament about his visit to Sri Lanka in July 1965.

Prof. Tariq Ramadan

Regarded as one of the most prominent Muslim theologians and intellectuals today, Prof. Ramadan was in Sri Lanka last week, to deliver the 18th annual Deshamanya M.A. Bakeer Markar commemorative lecture. At the end of his lecture, there’s an onslaught of people eager to seek him out.

If Prof. Ramadan was tired from the steady stream of meetings and lectures, there’s no trace of fatigue as he obliges for the occasional picture or pauses to answer a question. At a side of the hall his wife and daughter look on, also used to the interest which inevitably accompanies his public appearances around the world.

Of Egyptian descent, born and raised in Geneva, Ramadan grew up with siblings who were steeped in philosophy, an education of Islamic tradition within the family and a heavy interest in literature and culture. He had his initial academic grounding in philosophy and French literature and transitioned to Arabic and Islamic Studies. In the early ‘90’s, his family moved to Cairo.

“In fact at one point I thought I was coming back home and then I realized it was home for my Islamic roots but not home as to my culture. I realized, being in Egypt, that I was not really Egyptian by culture,” muses Ramadan in conversation with the Sunday Times.

“I was an Egyptian by memory and Muslim by principle […] but I felt that my culture was a European culture. There was a reconciliation with my principles but a kind of separation from a cultural background that was not exactly mine.”

Along with the largely favourable appellations, Ramadan has also had a fair share of brickbats. As a Muslim intellectual firmly rooted in the West, there are times when parts of the Muslim world dismiss him for not being ‘Muslim enough’, while the Western world finds he isn’t Western enough. Ramadan is acutely aware of this.

Referring to himself as a bridge between both worlds, Ramadan abides by two tenets – the first to never betray the principles of his faith and the second to listen carefully and rationally to both sides.

“You know that when you are a bridge, at the same time on both sides of the river, people are not going to be happy because they want you on their side only,” reflects Ramadan.

He explains that to be critical – especially when it means to be critical of Muslims when the need arises – is difficult and requires courage to face the swelling currents of protest on both sides of the river.

“This is not always easy, at the end there is no real place where you are safe – at one point in my life I was banned from three Western countries and six Muslim majority countries,” he explains wryly.

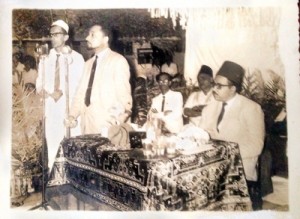

Fifty years ago: Dr. Said Ramadan addressing a meeting during his visit to Sri Lanka

As a prominent Muslim figure in the West, Ramadan speaks about the burden of authority and representation, careful to point out that he is not a representative for the entirety of the Muslim world.

“We [the Muslims] have a problem with authority. Who speaks for the Muslims and why are you deciding that somebody is ‘the one’ to represent the Muslims? It doesn’t have to do with knowledge, it has to do with emotion.

I am always saying one of the great problems that Muslims have today is that they are not following knowledge and wisdom, they are following personalities and this is why the leaders of the Muslims today are very often charismatic scholars and the problem with the charismatic leaders is the charisma,” he says.

The lack of a clear-cut authority, he cautions, sometimes results in the blind following of personalities which allows idealization to blunt critical thinking and emotional discourse to trump knowledge and rationality.

His lectures in Colombo revolved on Pluralism and its contemporary challenges; spirituality, ethics and social justice as well as contemporary challenges for Muslims today.

Highlighting the importance of pluralism he encouraged Muslims to have education and healthy debate within the community and promote clear communication to wider society.

He challenged the terminology of ‘integration’, urging Muslims to move into the age of post-integration with a focus on positive participation and contribution on a national level. Promoting universal justice and ethics, Ramadan stressed, was imperative in any society.

Currently a Professor of Contemporary Islamic Studies at Oxford University and with three books to be released later this year, Ramadan says the developments in academic discourse have been stimulating.

“It’s kind of paradoxical but with all these controversies, we have lots of people interested in Islamic subjects, disciplines and matters so you have to explain a lot and we have to be involved in the discussion at different levels – from the religious and spiritual levels, from the political level to the cultural one and even the artistic and the mystical.

There is a new interest and many questions of course,” explains Ramadan saying that there is still a lot to be done to drive debate and dispel the negative perceptions in the discourse.