She only wants to hear the word ‘sorry’

“Sorry” seems to be the hardest word to say in any language. For 70 long years, and counting, the Chinese and Korean people and their governments have been demanding this one word from the Japanese Government for what was a World War II military exercise in having what was then called ‘comfort stations’ – an euphemism for brothels, enslaving women in areas the Imperial Army had occupied whose soldiers needed to be served.

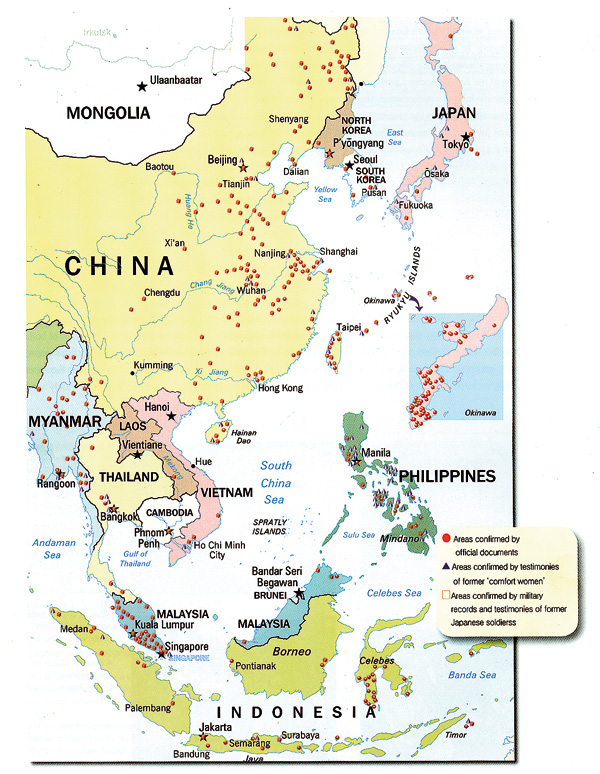

Lee Ok Sun: Still haunted by the memories. Top: Korean comfort women who became POWs near the border of China and Burma (Myanmar). Pic by Rumiko Nishino. This picture and map (below) courtesy Museum of Japanese Military Sexual Slavery catalogue, South Korea

Successive Japanese Governments find it difficult to swallow their pride and say the word. 89-year-old Lee Ok Sun is one of the surviving Korean victims. At the tender age of 15 back in 1942, she had been running an errand for her employer when she was kidnapped on the street by Japanese soldiers in Busan, Occupied Korea. Taken away to then Occupied China, she says “They (the Japanese) are waiting till we die”.

The sprightly old lady adds; “We were abducted or lured with fake jobs like nursing. We were treated as property. They made us suffer physically and mentally. We were not treated as humans.We were disposable items thrown at Japanese soldiers. The Japanese insist that we volunteered and that we want money. We are only asking for an apology – this will have to be resolved even after we die”.

She is one of the women – they don’t like to be called ‘comfort women’ – for in her words there was no comfort for the women – it was torture, who came out of the closet in 1988 to campaign for a public apology and reparation from Japan. Speaking at a House for Sharing, specially built for them on a property donated by a Buddhist organization, 40 minutes from Seoul, Ms. Lee says, “We were forced to take birth control tablets. Thousands became infertile afterwards. Any form of resistance to a sexual request was met with beating. I have been beaten so much.”

And when the war ended with the atomic bombing of the twin Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, what was her reaction to the death of so many innocent Japanese? She didn’t even know what had happened. All of a sudden the soldiers withdrew. But in some other camps the women were simply lined up and shot by the withdrawing troops.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe ran into the eye of a storm for his speech recently marking the 70th anniversary of the surrender of Japan and the liberation of China and Korea following the atom bombs. Abe fell short of expectations by merely endorsing a previous (1995) statement that went only as far as expressing “deep remorse” and a “heartfelt apology” for the “tremendous damage” inflicted.

Significantly, Abe’s grandfather was a cabinet minister during WWII and a recent opinion poll among Japanese conducted by the widely circulated Yomiuri newspaper found that 63 per cent of those surveyed felt Japan must not say “Sorry” in future.

But the Japanese Emperor, Akihito went beyond Abe’s steadfast refusal to apologise. Akihito, whose father Hirohito reigned (but did not rule) over Japan during the war and in whose name the Japanese Imperial Army fought that war, expressed “profound remorse”. It was the first time the 81- year- old used these words at an annual memorial to mark his country’s surrender to the Allies in 1945.

That the Emperor’s remarks fell short of an outright apology, but was still seen as a rebuke to PM Abe shows the difficulties Japan has in just saying ‘sorry’ – and being done with it.Ms. Lee pleads for solidarity from other countries. Korea’s attempts to take the issue to world forums like the UNHRC and the ILO have been thwarted by Japan and its economic muscle even neutralizing countries like the Philippines and Indonesia whose women were also the subjects of sexual slavery.

That the Emperor’s remarks fell short of an outright apology, but was still seen as a rebuke to PM Abe shows the difficulties Japan has in just saying ‘sorry’ – and being done with it.Ms. Lee pleads for solidarity from other countries. Korea’s attempts to take the issue to world forums like the UNHRC and the ILO have been thwarted by Japan and its economic muscle even neutralizing countries like the Philippines and Indonesia whose women were also the subjects of sexual slavery.

On her country’s 70th anniversary of Liberation, South Korean President Park Geun-hye made a moderate response to Abe’s statement a few days earlier, saying it “did not quite live up to the expectations”. She nevertheless didn’t want this issue to shackle her country’s future. It was “high time”, she said, for the two countries to move forward to a new future “guided by a correct view of history”.

Park has toned down her earlier demand for Japan to atone for her past sins, and now asks Tokyo for a “speedy resolution” of the issue because only 47 of those registered (in Korea) as victims are still living. Many never registered overcome by shame.

It was not until 1988, long after the war ended that the issue of these women surfaced thanks to the relentless work of some NGOs. In 1996 Sri Lanka’s Radhika Coomaraswamy as a UN Special Rapporteur on Crimes against Women wrote that the Japanese Government must take legal responsibility for its violation of human rights law. (Visit full report is available on www.sundaytimes.lk).

Japan meanwhile refuses to be haunted by the ghosts of WWII and despite continuing criticism from China and Korea (both North and South), the country has found the time is right to amend her Constitution to upgrade her Self Defence Force to a proper, once dreaded military apparatus.

On September 3, it is Beijing’s turn to celebrate her liberation following the capitulation of Japan 70 years ago. While South Korea opted out of a military parade to celebrate her liberation on August 15, China has no inhibitions in showcasing her military hardware. The Korean President was in two minds whether to attend the parade as the Chinese Red Army fought shoulder-to-shoulder with the North Koreans against the South no sooner WWII ended in a costly battle.

They have their own immediate problems as well to contend with. The North Korean leader continues to keep a finger on his nuclear bomb making threatening noises, but Ms. Sun-mi Lee, a typical young South Korean takes the theatrics in her stride. “No worries,” she says when asked if she is concerned, “a fortune teller told me I will live long”, she says with aplomb. A North Korean defector now with a PhD in Food and Nutrition under her belt dismisses these threats as “bluff”. Ms. Lee Ae-ran is more interested in getting Starbucks to buy her cookies.

For how long more can the Japanese defend the indefensible issue of the sex slaves during WWII? Only last week did China’s State Archives Administration release further documents of Japanese-run brothels during the war. These records alone show proof of 2,000 Koreans forcibly recruited, while historians put the total figure at 200,000 coerced into sexual servitude at the frontlines. China and Korea 70 years on, refuse to bury the hatchet.

That the Japanese also had their eyes set on Sri Lanka is evidenced by the 1942 Easter Sunday bombing of Trincomalee and Colombo. The Devas and the Gods protected this island-nation and her people from the ravages of WWII in comparison.

Comfort stations: The beginnings

| |