Sunday Times 2

All in the Penguin family

Pencils, lead and coloured, a drawing book, and a storybook about a family of penguins – these were the trophies we clutched to our chest one bright morning, half a century ago, as we marched out of The Corner Bookshop, a cosy street-corner store a few teetering steps from St. Michael’s Church, Polwatte, down a secluded inner street in Kollupitiya.

The book and the artwork materials were gifts from two aunts, Agnes Spittel and Lottie Jansz, sisters who overlooked and gently directed the growing up years of Older Brother, Younger Brother and self. Great-aunts, great teachers, great persons altogether – the two elderly ladies were a win-win combination that would bless and shower benefits on our formative years through the ’50s and ’60s.

The time would have been April, around Easter, in the mid-Fifties. We know it was Easter because of memory fragments of chocolate eggs, moss jelly eggs, and penguin eggs. That sunny morning, the Church-of-England aunts would have first taken us to see their church, St. Michael’s, and then chaperoned us to the bookshop round the corner.

Our second visit to The Corner Bookshop came more than half a century later. The bookshop had recently changed tone and hands. It was not a Christian store any more; the original sold Bibles and Christian literature, stationery and children’s books. The new owners specialised in textbooks and school stationery, but The Corner Bookshop legend, picked out in bits of brick above the entrance, had been preserved.

The aunts would have told us to choose a book, and we reached out for penguins. With children, as with many adults, the book cover was the deciding factor. The large-format hardback had a glossy blue-red-white-black cover, and was big on an unfamiliar branch of ornithology. There was another curious, visually teasing feature about the cover, which we will come to later.

On getting back to the aunts’ home, at No. 4, Police Park Terrace, we spread out our goodies on the white-painted rattan-weave table in the middle of the sitting room, and Agnes made us sit next to her on the green Rexine-covered sofa. She opened the book and started reading. It was the story of a day in the life of a penguin family. The bird clan, like ours, spanned three generations – children, parents, grandparents, and brothers and sisters. There was even an Aunt Bessie; we too had an Aunt Bessie (Elizabeth Spittel-Walbeoff), who lived in Kandy, in a hilltop house overlooking the old elephant bathing spot on the Mahaveli, where the river flowed past Katugastota.

In our unorganised head, elephants and penguins were awkwardly crossing paths and politely colliding. A steamy river gurgled with crocodiles on the other side of a snowscape dotted with polar bears. Our sense of the big world was flat and inclusive. The aunts, who supervised our progress in Writing, Reading, Geography, History, Sinhala and Numbers, would in due course orient us so we knew our Tropics from our Antarctics.

In our unorganised head, elephants and penguins were awkwardly crossing paths and politely colliding. A steamy river gurgled with crocodiles on the other side of a snowscape dotted with polar bears. Our sense of the big world was flat and inclusive. The aunts, who supervised our progress in Writing, Reading, Geography, History, Sinhala and Numbers, would in due course orient us so we knew our Tropics from our Antarctics.

The story centred on a penguin family day out on a frozen lake. The younger penguins go skating, while Father Penguin cuts a hole in the ice to fish for food in the freezing black water beneath. The youngest penguin skates into the hole and is rescued with much wing-flapping excitement. The happy ending shows a cosy family gathered under an ice-vaulted roof in a spacious up-market igloo. The penguins have a big laugh about the day’s adventure as they tuck into a meal of fried Arctic fish.

Looking back on that shiny, translucent, ice-cube of a memory, of a former childhood self stepping out of a corner bookshop, we note a symbol in the child’s hand, a sign of things to come. Books to come. In time, the penguins of that storybook would metamorphose and multiply into penguin mutants and variants, and other birds of a literary feather.

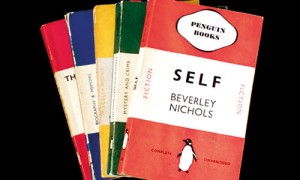

Two or three years on, the reading habit established, the child had started to collect and expropriate larger, fatter Penguins, those of the Bigger Book World, as well as book birds and bird books of other species, such as Puffins and Pelicans.

The precocious pre-teen pounced on any Penguin his meddlesome hands could find. The birds came in varying colours. The white-chested Penguins with dark Green wings were Detective stories, with titles like “Murder on the Orient Express”, “The Case of the Crooked Candle,” and “The Incredulity of Father Brown.” The birds with Red wings waved Travel titles like “Sea and Sardinia,” “Brazilian Adventure,” and “Siren Land.” The Blue-winged were academic birds, and came bearing titles like “What Happened in History,” “Microbes by the Million,” and “Totem and Taboo.” The Orange-winged were Novels, with adult themes and titles like “Loving”, “Love in a Cold Climate,” “Love in the Haystacks,” “Love and Mr. Lewisham,” “Sons and Lovers,” and “By Love Possessed.”

These marvellous “birds” were caged, read in secret, and released a week or two later – back to whoever was compelled to hand them over. The majority of the “bird” owners were music students, who had come to our home to learn to play the violin. Whatever books they carried in order to while away the time till it was their turn for a music lesson were wrested, like precious orc eggs, from their grasp. The students are now married professionals, most of them grandparents. Some are no more.

We remember, with deep reader gratitude, those many reluctant and submissive book sharers, including Nimalka (née Wijetillake), who introduced us to Erle Stanley Gardner; Rohini (née Wijekoon), whose mother was “terrified” of crime stories with “murderous” covers; the sisters S. and S. (née Gunasekera); Dawn Potger; Anula (née Aluvihare); the de Fonseka sisters; Christine Fernando; Isaac Kulendran, and tsunami victim, the late Beulah Ambrose (née Solomon), who lent us “Wuthering Heights.” There were others.

Come to think of it, there were no Penguins, no paperbacks, in the home of Agnes Spittel and Lottie Jansz. Their library contained only hardbacks, books from their teaching careers, and leather-bound volumes from the library of Lottie’s husband, the linguist and clergyman Paul Lucien Jansz. Even the detective stories were hardbacks, Collins Crime Club first editions.

Entering a book, hardback or soft, hardboiled or not, is like locking yourself in a private room. Once in, you close the door. Bolt it, lock it. You ignore knocks on the door, even taps on the windowpane.

To switch metaphor, you are like an ostrich with its head in the sand, oblivious of the world around you, assuming no one can see you.

Ostriches are desert birds. Penguins are birds of a frozen world. Over time, we learned to sort out our ostriches, penguins, pelicans and puffins, the real things, in our History and Geography classes with the two Aunts.

It has to be inserted here, better late than never, that Agnes and Lottie were the two most wonderful aunts in the world. You would not find two such aunts if you went searching from the North Pole to the South. They taught us to count and to read; they trained us to say “thank you” when someone performed a favour, showed a kindness; they reminded us to list our blessings; they pointed out that the servants in our homes were there only because we had the advantage, and that in a parallel world, where roles were reversed, we would be serving them in their homes, so consider yourself lucky.

That penguin book the aunts gave us circa 1956 had a glassy cover that played a trick on the eye. The red words of the title rested on the smooth deep blue of an Arctic sky. When you picked up the book, the red words started to slide, ever so slightly, over the viscous blue. The red appeared to shift a fraction. When the cover was tilted, the red slid in another direction, as if the words were glissading, but stopping one step later. The red and the blue seemed to have a little arrangement, an optical gimmick, between them. We would later see this visual shuffle happen in other blue-red contexts.

The world around us is all about colour, and the play of colours; about people and things, and the play between things and people.

Books are the best of all things, of the world’s magic and tricks, with their bewitching covers and the rest of it.