External shocks were very much the causes for the sorry state of our external finances. This is indisputable. Recent external shocks came in two waves that were diverse and dissimilar. At first it was the sharp rises in oil and commodity prices. The soaring prices of oil created a serious dent in the trade balance. That was not all, prices of other essential items such as wheat flour, milk, sugar and other basic foods rose manifold. All these resulted in a massive increase in the country’s import bill and consequently large trade deficits in 2007 and 2008.

The trade deficit reached an unprecedented amount of US$ 5,871 million in 2008 on top of a deficit of US$ 3,656 million in 2007. This massive increase in the trade deficit was brought about mainly due to a sharp increase in the import bill. This trade deficit was mainly due to the exceptional increases in price of oil and a number of essential items, especially food commodities such as wheat, sugar, dhal and milk. Oil imports alone cost US $ 3368 million or 24 percent of the total import bill of US$ 14,008 million. On the other hand, the country also benefited from higher prices of commodities, especially rubber and tea. Yet the increased earning from these did not compensate for the increased import expenditure. The trade deficit that reached a mammoth US$ 5800 million in 2008 was a severe strain on the balance of payments and external reserves of the country.

|

The second wave of external shocks was the converse of the first. Commodity prices declined unexpectedly and rapidly and developed countries were enveloped in a recession that was considered to be the worst since the Great Depression of the 1920s and 1930s. This affected our exports, both agricultural exports like rubber and tea, and manufactured exports like garments and rubber goods. The reduced prices of imports, especially of oil imports have given significant relief to the trade balance but inadequate to turn the persistent trade deficit into a surplus. Even though this year’s trade deficit is likely to be lower than last year’s, it would still be a strain on the balance of payments. Export growth is likely to be modest or even negative and therefore a detrimental factor in the trade balance.

Two other features require to be brought out. The country has been able to sustain large trade deficits and in fact have small balance of payments surpluses owing to two main reasons. First, remittances from Sri Lankans abroad have financed over a third of import expenditure. The increase in private remittances especially in 2007 and 2008 are attributed to the higher incomes of oil producing countries in West Asia. This adds a complication to the current situation as it is feared that remittances may decline this year owing to the lower incomes in West Asian countries. Already significant numbers of workers have returned from these countries due to the shut down of construction and other service industries.

The second feature in the balance of payments has been the country’s resort to large sums of foreign borrowing. What one borrows today has to be returned tomorrow. Similarly the financial investments that come in today will be taken out tomorrow. This happened last year when the government repaid loans and investors took their money out. These were contingent liabilities that give relief in the current year but cause strains later on. In this context one must note that the IMF borrowing would be quite different in that it is likely to be a long term loan at low rates of interest.

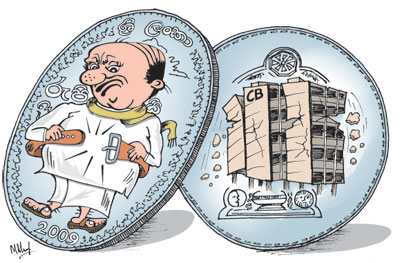

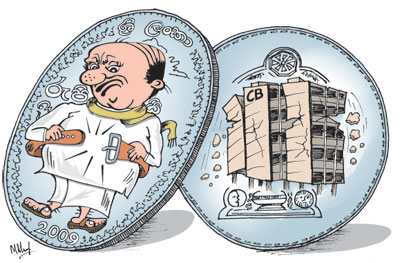

While accepting that these external shocks were important factors in creating the balance of payments problem, there is an equally important side of the coin with respect to the internal situation. The stark and unpalatable truth is that the management of the economy was deficient. The government time and again ignored basic economic principles as if they did not matter. One of the fundamental deficiencies was the large fiscal deficits that have characterized the public finances of the country. The excuse for these deficits was the ongoing war. Again, it is true that the country was fighting an expensive war, but what about other expenditures that were wasteful? It is precisely at a time of war that a government and people should tighten their belts so that the war expenditure is a sustainable one. This was not to be.

Borrowing to solve the immediate problems became a strategy of economic management. The large public debt resulted in a huge debt servicing burden. About 90 percent of revenue went towards servicing the debt. Consequently, on the one hand important current and capital expenditures were inadequate, and on the other hand, deficits grew and contributed towards an ever increasing public debt. The inflationary pressures meant that the country’s exports were getting less and less competitive in international markets and export growth fell at the same time as import costs were growing.

A yardstick of the mismanagement that occurred prior to the sharp rises in international prices of oil and food and the recession, is that the rate of inflation of neighbouring countries was much less. They kept their fiscal deficits at around their growth rates and adjusted their exchange rates to cope with the erosion of markets for their goods. Not so Sri Lanka that had its wiser counsel to not pursue an adjustment in economic policies. That is the reason why we are facing a more serious problem in the external finances than our neighbours. Pakistan is the other country that is in economic chaos. We can take solace that we are a less failed state than Pakistan. The global recession that is occurring in developed countries is not a creation of developing countries. Yet as Manmohan Singh, the Indian Prime Minister told leaders of developed countries, though the less developed countries were not responsible for it, they will suffer more from it. Once again the country must respond to it through economic policy measures that mitigate the ill effects of the global recession.

Turning to the IMF for assistance we hope would make us to follow good economic management principles. This is particularly so with respect to following a prudent fiscal regime.

Time and again independent economists, think tanks and the business community have advised the government on the need for fiscal discipline. These were ignored. Now with the government turning to the IMF at this crisis, it may be possible for the international body to insist on fiscal discipline and conform to the Fiscal Responsibility Act passed by parliament and ignored by the executive. May be the crisis is an opportunity to reform the country’s economic policies, especially fiscal policy and put it back on an economic recovery path.

|