Window into Emily's pastThere is a reverent silence in the room. We look at the bed she slept in, where she lay perhaps, with her thoughts and her dreams. The window, from which she observed the world outside, weaving them into the poems that she wrote. Beside her bed is a copy of a fragmented poem in her own handwriting. Although over a hundred years have passed since Emily Dickinson died, her essence permeates the room where she created her masterpieces, a room which has become almost a shrine in the house which draws visitors from all over the world. Emily has been my favourite poet ever since I studied the poem Nobody in school. A poem that appeals to every typical adolescent! And now here I am in her birthplace and home in the town of Amherst, Massachusetts, paying homage to the poet whose unique work made an indelible mark on world literature.

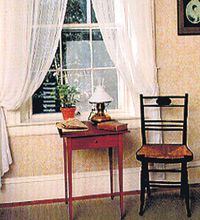

The Homestead, probably the first brick house in Amherst, was built around 1813 for Emily's grandparents. Emily was born here in 1830, and though the family moved out for a short period, she spent most of her adult life here until her death in 1886. Today it is a National Historic Landmark in the USA and has been painted in its late-nineteenth-century colors to interpret more accurately the house, as she knew it. Our guide is Nonni, a vibrant, silver haired lady who is obviously passionate about Emily and her work. She speaks of Emily, as though they met just the other day, and guides us through her home with the intimate knowledge of one who has been a frequent guest. Of her writing, one can always read in books, but it is of the life she lived that Nonni speaks. We enter the parlour where there are several portraits hung on the wall – the only existing one of Emily herself, when she was sixteen, of her parents, and one of whom Nonni describes as "the only man we know for certain that Emily loved" – Judge Otis Lord, a widower who was 18 years her senior. There is also a piano, a replica of Emily's own, where she often pounded out 'weird music' of her own composition, often into the wee hours. "Those who had heard it, agreed it was weird," remarks Nonni, adding that it was a pity she did not write down these compositions. Her poetry was so original and so far ahead of its time, that it is quite possible she may have been a musical genius as well. Emily Dickinson was known for her reclusiveness, writing in 1868, "I do not cross my father's ground for any house or town." However, as Nonni reminds us, her father's ground encompassed over 14 acres, and although Emily turned away from the world, she did not turn her back on it – an important distinction. Emily was worldly and sophisticated, her intellectual curiosity closely binding her to the world outside. Nonni describes her as "ruthless and driven," sacrificing the material pleasures of life to create her poetic masterpieces. We go upstairs to the room, which was Emily's private sanctuary. It was here, in this sparsely furnished space, that she spent hours perfecting her poems. For her, the creation of a poem involved several stages, and she compiled her poems into small packets now termed "fascicles." Nonni passes around a copy of an original fascicle in the poet's loopy handwriting.

Emily was also known to have worn only white after she chose to become a recluse. A glass case outside her room displays a haunting re-creation of one of her elaborately woven white house dresses. It would have been slightly short on her five foot four inch frame though, says Nonni, asking us if we could guess by what means her height was deduced. Most of us shake our heads, but one man asks, "was it by her coffin?" Nonni smiles, yes, she says, from records about her coffin, which is usually about two inches longer than the body. We are now led to the house next door, the Evergreens, which is a part of the Emily Dickinson Museum, and whose occupants played an integral role in her life. It is the house of her brother Austin, his wife Susan, and their three children. We step into a time capsule of a prosperous nineteenth century home. Here, unlike in Emily's own house, nothing has been removed. This, says Nonni, is because of Emily's niece Martha Dickinson Bianchi, who, though unknown in the present, was a famous writer in her time. Emily herself was only discovered after her death, gaining popularity long after her house had been occupied by others and her furniture passed through many hands. It was between Martha, her brother's mistress Mabel Loomis Todd, and Emily's sister Lavinia, that a melodrama was played out after Emily's death regarding the publication of her poems. In the hushed voice of one who is revealing the latest neighbourhood gossip, Nonni speaks of the affair between Mabel and Austin, which was, she says, very public. Mabel was a frequent visitor at Emily's home as well, welcomed there by Emily and Lavinia "because she made their brother happy." After Emily's death, when Lavinia discovered a locked box containing around 1800 of her poems, it was Mabel that she turned to for help with publication. Betrayed and infuriated, Martha Dickinson sought to publish her own collection of Emily's poems. It was largely due to their separate efforts that Emily's unique voice began to be heard and appreciated worldwide. Emily herself shunned publication, saying in one of her poems, Publication – is the Auction Of the Mind of Man. Only seven of her poems were published during her lifetime, and those without her consent. Is it really almost a hundred years ago that all this took place? Nonni regretfully says that the tour is over, and gently releases us from the spell she has woven. As we step out again into the crisp spring air, there is one last stop to make. We drive down to the small New England graveyard where Emily is buried. Here is the tombstone with the epitaph Lavinia later had inscribed, "E.D. Called Back" reminding us of a life lived in a realm beyond the earthly. Recent visitors have left numerous tokens on the stone – coins, flowers and even a small orange plastic dragon. As I run my fingers over the inscription, I remember the words from her poem: "Because I could not stop for Death, |

|

||||||

|| Front

Page | News | Editorial | Columns | Sports | Plus | Financial

Times | International | Mirror | TV

Times | Funday

Times || |

| |

Reproduction of articles permitted when used without any alterations to contents and a link to the source page.

|

© Copyright

2008 | Wijeya

Newspapers Ltd.Colombo. Sri Lanka. All Rights Reserved. |