A people broken on the wrack of historyMy journey through the horrors of Partition Even after 60 years of independence, the partition, more so the journey from my hometown, Sialkot, Pakistan, to the Wagha border, India, is etched in my memory to the last details. I heard on August 12 Qaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah, founder of Pakistan, assuring us: "…You may belong to any religion or caste or creed that has nothing to do with the business of the state… We are starting with this fundamental principle that we are all citizens and equal citizens of one state." Still, I had to leave Sialkot because I was a non-Muslim, as was the case with Muslims living in East Punjab and elsewhere. Ten lakh people were killed and two crore uprooted in the wake of forced migration. The governments of India and Pakistan had refused to accept the exchange of population when they had agreed to divide the subcontinent on the basis of religion. The Punjabis on both sides suffered the most.

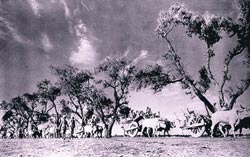

The minimum that the two governments can do is to say "sorry" to each other. They should pass a resolution in their respective parliaments to express regret over what happened. Nothing more, nothing less. Now that the relations between the two nations are on the mend, a formal regret may bury that part of the past which should have been effaced long ago. I left Sialkot on September 13, 1947, almost one month after the birth of Pakistan. My parents, two brothers and I decided to visit India and stay there until the disturbances subsided. Even when I packed a small handbag, I was sure that I would be back soon. My mother gave me only Rs 120. I could borrow more from my aunt living in Delhi where I was heading to. The parting was short and quick. A Hindu military officer, on transfer, who had agreed to take me to India in his jeep, was in a hurry. I still had not reconciled to the prospect of leaving my family behind. We promised not to say goodbye but our eyes were wet. We promised to meet in Delhi at the aunt's place on October 12, one month later. My last advice to them was not to travel together. The migrants were being attacked on the way. As I got into the jeep, I looked towards my mother who was trying to hold back her tears. My father was distraught. My brothers were laughing but how unreal was their laughter. Sialkot is 15 kilometres away from the main road. It was all quiet when we drove through. Only after reaching the main road, going to Lahore and the Indian border onward, did I realize that there was no going back. Thousands and thousands of people thronged the road, a small stream of people coming from India, the Muslims, and the big one going towards India, the Hindus, and the Sikhs. I could not imagine how my aged parents would make it. Our jeep was in the midst of a sea of humanity, inundating every inch of space - the roads, the fields and the elevated rail-track. People rushed towards us. Some determined men and women stood on the road. They wanted us to hear them. It was an avalanche of migration. Lakhs of people were on the move on both sides. None expected it. None wanted it. But none could help it. The two countries blamed each other as their governments tried to grapple with the problems of migration and rehabilitation.

An old Sikh, with a flowing beard flecked with grey, nudged me and tried to hand me over his grandson. "He is all we have in the family," he begged. "Take him to India. At least he should live." A middle-aged woman tried to put her child in the jeep. "I will trace you and collect my son," she said. How could I take their children with me? Every human being has limits to how much he or she can soak in grief and joy, good and bad. I reached the level where I could take no more. My feelings had been dulled. It was as if I was left with no emotions to react. A story of brutal murder or gang rape did not move me any more. I just listened to gruesome happenings as if I was going over an exercise. Any narration, however touching, was like the one I had heard earlier. The cruelty was the common factor. At least, some of them had their story off their chest. They probably felt better and withdrew to make room for the jeep to pass. It was still a long way to the border. The major did not want to lose the daylight. The jeep sputtered into motion. I looked back. I could see outstretched hands wanting help. The spectacle jolted me out of wishful thinking that things would normalize. As the jeep drove along the Grand Trunk Road, I saw bodies on both sides the smouldering remains of burnt vehicles and the pieces of luggage strewn all over. More hideous was the sight of children impaled on swords or spears and women and men cut into pieces. They bore testimony to the hell that the people on both sides had gone through. And all in the name of religion which was supposed to represent values. The subcontinent's composite culture and pluralistic society going back to hundreds of years lay in tatters. It was late in the afternoon when the jeep reached the outskirts of Lahore. We were told that a caravan of Muslims had been attacked at Amritsar and that the Muslims in Lahore were waiting on the roadside to take revenge. We got down, and waited in fear and silence. There was some stray shooting in the distance. The stench of decomposed flesh from nearby fields hung in the air. We could hear people shouting slogans, Allah hu Akbar, Ya Ali and Pakistan zindabad. But it was far away. We set off again. There was nervousness as we approached the border. And then we heard Bharat mata ki jai. It was great to be alive. There was still daylight. As I looked out, relieved and happy, I saw people walking in the opposite direction. They were Muslims. I saw the same pain etched on their faces. They trudged along with their belongings bundled on their heads and their frightened children trailing behind. They too had left behind their home and hearth, friends and hopes. They too had been broken on the wrack of history. A caravan of people was going to Pakistan. We stopped to make way for it. We looked at one another with understanding, not fear. A strange link came to appear between us. It was spontaneous kinship, of hurt, loss and helplessness. Both were refugees. The writer is a veteran Indian journalist, diplomat and former Rajya Sabha member |

|| Front

Page | News | Editorial | Columns | Sports | Plus | Financial

Times | International | Mirror | TV

Times | Funday

Times || |

| |

Copyright

2007 Wijeya

Newspapers Ltd.Colombo. Sri Lanka. |