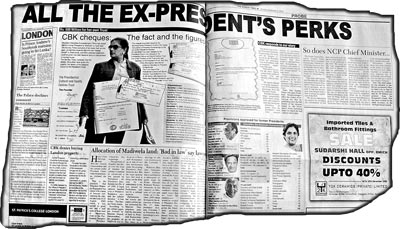

By way of deceptionCountry’s highest court rules that former President Chandrika Kumaratunga abused her authority to obtain retirement perks On Thursday, the Supreme Court held that former President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga should vacate the official residence she secured for herself as the Head of the Cabinet of Ministers saying that she had abused her authority when in office and had practised serious deception in the manner in which she secured that property. In a stinging unanimous judgement, the country's highest court also blamed incumbent Prime Minister Ratnasiri Wickramanayake and Urban Development Minister Dinesh Gunawardene for misleading the Cabinet in their efforts to give the former President properties she was not entitled to in law. The bench comprised Chief Justice Sarath N. Silva, Justice Shirani Thilakawardene and Justice Gamini Amaratunge. The court held that the petitioners -- three lawyers -- appearing as citizens had seen a news item (in The Sunday Times) on December 4, 2005 under the headline " All the Ex-President's Perks" which detailed the allocation of land at Madiwela, 36 vehicles, security staff, private staff totalling 248 persons to outgoing President Chnadrika Kumaratunga and how she had withdrawn Rs. 600 million from the President's Fund (to a private fund she was directly engaged in).

These lawyers had written to the Secretary to the Cabinet asking for more information, but such information had been refused. Therefore, the Court rejected the objections of the former President's lawyers and held that when a wrongful and unlawful grant of facilities and benefits at the highest levels of the Executive is being challenged, strict rules of pleadings cannot be insisted upon. Madiwela property The first allegation was that the former President tried to obtain a property at Madiwela to construct a private residence for herself. The law that governs such benefits for retiring Presidents, the Presidents' Entitlement Act No. 4 of 1986, states that such a President is entitled to a government bungalow, but that if such a bungalow was not available she was entitled to 1/3rd of the pension as rental allowance. Then President Kumaratunga justified herself asking for a property on the grounds that a 'Ministerial type bungalow' will cost Rs. 400,000 a month, and that an additional Rs. 1 Million will have to be spent on repairs, as well as payment of electricity bills etc. The lawyers pointed out that the Madiwela property was what President Kumaratunga had originally intended to build her official "Presidential Palace", and that Rs. 800 million had already been spent to develop the property. The minister concerned did not contradict this position, and his Cabinet Paper stating that this property was "insignificant" compared to what the ex-President was surrendering by way of not accepting a government bungalow was "misrepresentation of facts" because Rs. 800 million had already been spent on developing this property. The Court questioned the Minister (of Urban Development Dinesh Gunawardene) saying that his Cabinet Paper referring to a "free-hold" allocation was not known to the law of Sri Lanka, and that "it is significant" that the deeds vesting the property in the hands of President Kumaratunga by the Urban Development Authority were done the "very next date" from the date the decision of the Cabinet of Ministers was communicated. It was pointed out that the within a matter of a brief period of time since the Supreme Court held that President Kumaratunga's term of office had to come to an end (on a date earlier than she expected it would end), "the land had been surveyed, a Cabinet Memorandum submitted and approved and a deed containing a free grant issued". The premises at Independence Square It was the Minister of Public Security, Law and Order (Ratnasiri Wickramanayake) who put up a request on behalf of then President Kumaratunga for a government bungalow at Independence Square. No mention was made to Minister Dinesh Gunawardene's request -- and grant -- of the Madiwela property when this request was made. The Wickramanayake request also asks for 198 policemen, 18 vehicles, and 18 motorcycles. The Court held that this request "supressed" the fact the Cabinet had already given a free grant of a property at Madiwela to President Kumaratunga. President Kumaratunga, in her note to the Cabinet (where she says that she is requesting this official bungalow because she wishes to play a meaningful role in the country's public affairs after her retirement), knowing fully well that she had already got a land free in lieu of a residence, has stated that she has already selected premises No. 27, Independence Avenue, Colombo 7. Minister Wickramanayake called it a "house to reside in", while President Kumaratunga called it "an office". President Kumaratunga calling it an office with a staff of 63 is a "patent misrepresentation" since the office staff included five butlers and a cook, the Court held. The Court pointed out that President Kumaratunga began repairing these premises even before Cabinet approval was granted, and held that the former President adopted a "fiscal ruse" to incur unauthorized expenditure without any recourse to tender procedures and in flagrant violation of the guidelines which she herself laid down as Minister of Finance, personally selected the contractor and agreed the price payable. The Court referred to the "strident objection" on the part of the President's lawyer to call for these documents."The documents and the facts set out above clearly establish that the entire sequence of events in regard to the premises No. 27, Independence Avenue is an abuse of authority on the part of the 1st Respondent (former President Kumaratunga) and marked by a serious deception i.e. the suppression in both papers to the Cabinet, the previous free grant of the Madiwela land in lieu of the entitlement to a pension and a residence", the Court held. Allocation of staff The Court held that the salient aspects of good governance have "been thrown to the winds" by then incumbent President in participating in decisions relating to her own staff after she had retired. She had herself made a note to her own sitting Cabinet on what her entitlements would be after her retirement. The Court also explained why they entertained this application by three citizens, saying that ordinarily, an infringement of a fundamental right is alleged when the impunged wrongful act on the part of the Executive or Administration affects the rights of the aggrieved party. The petitioners' case is presented on a different basis where they seek to act in the public interest. They have shown that the former President and the Cabinet of Ministers of which she was the head, being the custodian of executive power, should have exercised that power in trust for the people, not for the benefit or advantage wrongfully secured, where then, there is a public interest to seek a declaration from this Court. The Court noted that after this application was filed in the Supreme Court, former President Kumaratunga returned the Madiwela land by a notarial instrument. However, the Court made a formal declaration stating that the decision to grant the land to her is contrary to law, and of no force or avail in law. Similarly, declarations were made that the decisions which give a right to former President Kumaratunga to the use and occupy the premises at No. 27, Independence Avenue are of no force or avail in law. Still further, the Court held that decisions taken by the then Cabinet of Ministers regarding the former President's staff, both security and personal, had no force or effect in law. Former President Kumaratunga would now be entitled only to the benefits as provided in the Presidents Entitlements Act No. 4 of 1986 - which is an appropriate residence free of rent and where an appropriate residence is not available to a monthly allowance of 1/3rd of her pension. The Court specifically held that premises No. 27, Independence Avenue which has not been used as a residence cannot be considered as an appropriate residence under the Act. She would be entitled to a monthly secretarial allowance and for official transport and facilities relating to transport in accordance with the Act. |

|| Front

Page | News | Editorial | Columns | Sports | Plus | Financial

Times | International | Mirror | TV

Times | Funday

Times || |

| |

Copyright

2007 Wijeya

Newspapers Ltd.Colombo. Sri Lanka. |