Missing Professional Leadership in Disaster Governance: Lessons from Cyclone Ditwa

A country that invests heavily in free education deserves professional leadership in return; the impacts of Cyclone Ditwa raise critical questions about whether that responsibility was fully honoured.

By Dr Duminda Perera (P. Eng, Ph. D)

Opinion / Disaster Governance

Cyclone Ditwa will be remembered not only for the devastating rainfall and floods it unleashed across Sri Lanka but also for the troubling silence from many of those entrusted with technical knowledge and moral authority. Engineers, academics, and technical experts occupy a privileged position in Sri Lankan society. They possess specialist training in assessing risks, modelling hydrological consequences, understanding climatic threats, and advising governments and the public when danger is imminent. When a major climate hazard such as Ditwa unfolds, it is fair — and necessary — to ask whether those professionals fulfilled their duty of care to the public.

This question matters now more than ever. Climate-driven extremes are no longer rare, and Sri Lanka has endured repeated cycles of flood disasters, emergency responses, public hardship, and post-event analysis. Yet in the case of Ditwa, there is little visible evidence that technical leadership emerged in a timely, coordinated and professional manner. The issue is not whether individuals worked hard; many surely did. Rather, it is whether the country’s collective professional and academic community acted proactively, translated meteorological forecasts into actionable flood-risk intelligence, and stood publicly as protectors of the public interest.

The ethical duty of technical professionals

Professional engineers, hydrologists, urban planners, and scientists share a common ethical foundation: protecting human life and safety must take precedence over all other considerations. Around the world, professional codes of ethics make this principle explicit. Academics, meanwhile, hold another form of public trust — the responsibility to apply knowledge for societal benefit, not merely for institutional prestige or career advancement.

In Sri Lanka, this responsibility is both professional and moral. Nearly all Sri Lankan professionals are products of a free public education system, fully subsidized by citizens’ tax contributions, from Grade 1 through university graduation. Their degrees and credentials exist because of public investment. The privileges and respected status they enjoy are made possible by ordinary people in this country. That reality creates an undeniable moral obligation: when danger threatens society, professionals must not stand silent or wait for instructions. They must lead.

Was the available information used effectively?

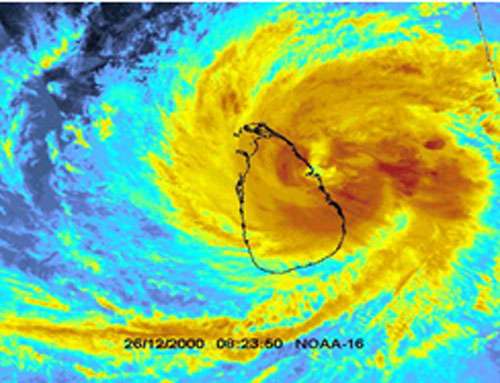

Sri Lanka did not face Cyclone Ditwa without warning. Multiple meteorological authorities, including the Indian Meteorological Department and Sri Lanka’s Department of Meteorology, issued advance bulletins. Global weather forecasting systems were already projecting intensifying rainfall and storm-track risks. High-resolution satellite rainfall estimates were available. Historical data clearly identify which districts are most prone to riverine and flash flooding. None of this information was secret. Much of it was publicly accessible.

The critical question is this: Did Sri Lanka’s professional and academic community translate that information into meaningful hydrological risk assessments? Were river basins modelled to estimate expected water-level increases? Were high-risk floodplain settlements identified early? Did hydrologists and water resource professionals provide guidance to municipal authorities? Did engineers assess whether existing infrastructure and flood defences would be overwhelmed?

Each year, Sri Lankan engineers, academics, and technical specialists receive valuable opportunities for overseas training, postgraduate study, professional exchanges, and capacity-building programs funded by local and international partners. These investments aim to strengthen national capability and ensure that, during critical events like Ditwa, advanced technical knowledge and global best practice are applied rapidly and responsibly. Such opportunities should not be viewed merely as pathways to career titles, promotions, or professional prestige. They carry a duty to translate learning into public protection and effective disaster-risk governance when the country needs it most.

Perhaps some analyses were conducted internally or individually. If so, they did not translate into visible, actionable guidance for the public or local authorities. Risk information confined to institutional meetings or technical memos is not disaster governance — it is administrative routine.

The silence of technical leadership

During high-impact hazard events, the public expects — and deserves — to hear directly from experts, not in abstract technical language, but in clear, accessible, actionable guidance. People need to know whether their homes are at risk, whether rivers are rising, whether sudden evacuation may be necessary, and how to reduce exposure.

In other countries facing similar events, national engineering bodies, university departments, hydrology research centres, and academic experts regularly speak to the media, publish rapid assessments, issue modelling analyses, and openly advise governments. This is not a political activity. It is a service to society.

During Cyclone Ditwa in Sri Lanka, that level of coordinated, proactive expert engagement was largely absent. The silence was especially striking given the number of distinguished engineering and academic leaders in the country. This was particularly evident in the Central Province — one of the hardest-hit regions — which also hosts a major national university and several respected research institutes with strong technical capacity in hydrology, engineering, and environmental sciences. These institutions are well placed to play a proactive role in risk interpretation and public advisory support during national emergencies. The point here is not to assign responsibility to any individual but to highlight a broader systemic failure to mobilize the country’s considerable professional and academic expertise when it was most needed.

What were the universities doing?

Sri Lanka’s universities host hydrologists, climatologists, geographers, engineers, and disaster risk specialists who have studied flooding for decades. Many hold postgraduate degrees from world-class universities, have international training, and have access to global datasets and models. Yet university-led analysis or guidance before or during the Ditwa crisis was scarcely visible to the public.

Where were the rapid technical assessments?

Where were the hydrological scenario maps?

Where were the expert panels briefing authorities?

Where were the warnings highlighting landslide-prone slopes?

Where were the student-led data analysis initiatives supervised by academics?

Universities cannot remain confined to classroom-based roles during national emergencies. Their laboratories and expertise must serve the public when risks escalate. If the academic sector remains passive, Sri Lanka risks losing one of its most potent tools for disaster risk reduction.

Competence is not only knowledge — it is leadership

Competence is often misunderstood as technical skill alone. In reality, professional competence comprises:

- acting promptly

- interpreting uncertain data responsibly

- communicating risk truthfully

- coordinating across institutions

- prioritizing public safety over professional comfort

If specialists see danger approaching but hesitate to speak because of fear of controversy, professional hierarchy, or political perception, the system has failed. Expert knowledge serves its purpose only when it is applied to protect the public.

A question of accountability — not blame

The purpose of this reflection is not to target individuals or institutions but to examine whether Sri Lanka’s professional culture — across engineering, hydrology, emergency management, and academia — has become too passive, too cautious, and too disconnected from public duty.

Disasters expose not only weaknesses in infrastructure but also weaknesses in leadership, communication, and institutional courage.

If Sri Lanka’s professionals feel constrained from acting publicly, we must ask why. If systems for professional advisory engagement during emergencies are weak, they must be strengthened. If professional bodies lack crisis protocols, they must develop them urgently. If academic institutions are uncertain about their societal role during disasters, that culture must transform.

The moral obligation of publicly educated professionals

In Sri Lanka, the path to becoming an engineer, scientist, doctor, or academic is funded by taxpayers. This is a rare privilege worldwide. It means that every professional diploma/degree carries a social contract. That contract does not end at graduation. It extends throughout one’s career, especially during national emergencies.

Ordinary citizens who contribute to this system do not demand wealth or privilege from professionals. They demand competence, integrity, foresight, and public leadership. They expect that when danger approaches, experts will step forward — not to criticize the government after the fact, but to warn and guide before and during the crisis.

Cyclone Ditwa revealed that this expectation remains unmet.

Moving from silence to service

If there is one lesson Sri Lanka must draw from Ditwa, it is this: professional responsibility must evolve from passive technical compliance to active public stewardship.

This requires systemic reforms:

- Professional bodies should create standing emergency advisory committees to issue guidance before and during major weather events.

- Universities should establish operational climate-risk observatories to translate data into actionable intelligence.

- Hydrology and engineering departments must maintain real-time flood modelling capabilities.

- Professional ethics training should emphasize societal duty, not merely technical standards.

- Government agencies should formally integrate external expert panels into disaster response frameworks.

Above all, a new culture must take root: when extreme climate hazards emerge, experts do not wait. They lead.

A turning point, not another chapter

Sri Lanka cannot afford another predictable cycle of disaster followed by predictable regret. Cyclone Ditwa must be the turning point when the country demands visible, proactive, ethically grounded leadership from its technical and academic elite. Climate extremes will intensify. Vulnerable communities will remain exposed. Political systems will continue to struggle under pressure. In this context, the expert community cannot remain reactive or silent.

The public entrusted them with education, privilege, and authority for a reason.

The question now is whether they will honour that trust the next time danger approaches.

Dr. Duminda Perera is a Disaster Risk Reduction and Water Security Specialist (Civil Engineer & Hydrologist) with expertise in flood risk management, water security, and early warning systems. A former Senior Researcher at the United Nations University, he has over 15 years of international experience in Singapore, Sri Lanka, Japan, Canada, and within the UN system.

-

Still No Comments Posted.

Leave Comments