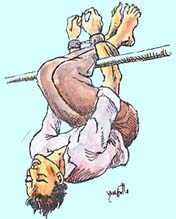

Police brutality:awareness key issue

"JUSTICE" this month looks at the question why

human rights violations continue to take place in the country with such

impunity inspite of increased action taken to protect human rights in courts

of law. The page features a thought provoking guest column by a former

judge of the Supreme Court, K.M.B.B. Kulatunge on the practical realities

of the observance of human rights in Sri Lanka along with an interview

with an Indian lawyer and rights activist Biju Verghese who comments on

issues relevant to police brutality and custodial violence and the role

of the Indian Supreme Court. "JUSTICE" also contains a synopsis

of a recent judgment of the Sri Lankan Supreme Court

By Kishali Pinto Jayawardena

Rights protection by the Sri Lankan Supreme

Court has been most marked in the area of unlawful arrest and detention

and the prohibition against torture and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment.

The law has, in fact developed to a point where medical evidence of

injuries has not been looked upon as essential in all cases, the Court

declaring that in appropriate circumstances an allegation of violation

of Article 11 ( torture and cruel inhuman and degrading treatment) could

be proved even in the absence of medical evidence. Again, a specific police

officer need not be identified as being responsible for the brutality and

liability is established once it is proved that custodial violence had

taken place inside the police station.

Despite such pronouncements

by the Court however, police brutality in normal reportage of crimes, quite

apart from action taken under the emergency laws of the country, continues

unchecked. Directions given by the Court to the IGP to take action against

particular police officers named as being responsible for violations are

not heeded and the frustration of the Court with this non-compliance has

now become virtually legendary. Despite such pronouncements

by the Court however, police brutality in normal reportage of crimes, quite

apart from action taken under the emergency laws of the country, continues

unchecked. Directions given by the Court to the IGP to take action against

particular police officers named as being responsible for violations are

not heeded and the frustration of the Court with this non-compliance has

now become virtually legendary.

India has had similar and perhaps more pervasive problems than Sri Lanka

where custodial violence and police brutality is concerned. Indian advocate

Biju Verghese, a public interest lawyer in the Karnataka High Court who

has specialised in this area of the law spoke to me recently regarding

the problems that Indian judges and lawyers face when dealing with these

questions. Following are extracts from his interview:

Q. Custodial death and violence is a recurrent phenomenon related

to patterns of abuse by the police. This is a matter of grave concern in

the region. How serious is this problem in your country?

A. Many provisions of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

( 1948 ) which marked the emergence of an international trend in the protection

and guarantee of certain basic human rights have found pride of place in

the Indian Constitution and have been enumerated in Part III. Article 21

provides that "no person shall be deprived of his life or personal

liberty except according to procedure established by law".

Despite the values proclaimed by international human rights instruments,

safe-guards provided in the Constitution and other legislation, custodial

violence and violation of basic human rights in my country continue unabated.

National and international media has increasingly focussed public attention

on blatant human rights violations committed by persons who are supposed

to be protectors of the citizen. The perpetrators of these inhuman violations

have found ways and means of circumventing the law and in many instances

the judicial officers at the lowest level have turned a blind eye or have

become insensitive to such violations and arrest and torture of a person

on the instructions of influential persons in the society or for extortion

of money has become a common phenomenon.

Q. What contribution has the Indian judiciary made towards checking

this trend?

A. Some recent decisions of the Supreme Court of India attempt

to effectively address some of these pressing issues. The courts have attempted

to do this by bringing about transparency of action and accountability

in matters of exercise of State power. A recent case, (D K Basu v. State

of W.B. [(1997)1 SCC), laid down certain mandatory requirements to be adopted

by authorities in all cases of arrest or detention. These requirements

can be briefly summarized as follows: All personnel carrying out the arrest

and interrogation must bear clear identification with name and designation;

An arrest memo is to be prepared at the time of arrest containing the time

and date of arrest, which is to be signed by a witness and countersigned

by the arrestee; a friend or relative of the arrestee shall be informed

of the arrest and the place of detention; the arrestee shall be informed

of this aforesaid right as soon as he is arrested; an entry should be made

in a diary at the place of detention regarding the arrest and also the

name of the friend or relative of the arrestee who has been informed should

be entered in this diary; the arrestee should be examined at the time of

arrest and any injuries present on the person should be recorded in an

inspection memo to be signed by the arrestee and the officer effecting

the arrest; the arrestee should be subjected to medical examination every

48 hours during his detention by a doctor from the approved panel of doctors;

copies of all the aforesaid documents should be sent to the concerned magistrates;

the arrestee may be permitted to meet his lawyer during interrogation.

Q. Have these directions been complied with by police officers? What

happens in the case of non-compliance?

A.In the Basu case, the Court took note of the fact that the

earlier decision of a similar nature had not had effect at the ground level.

It was therefore expressly stated that failure on the part of any police

officer to comply with these requirements shall, apart from rendering the

official concerned liable for departmental action, also render him liable

for contempt of court. The Court further directed that these requirements

laid down are to be forwarded to the Home Secretary of every State. The

Secretaries are obliged to circulate this to all police stations under

their charge. All State Governments were moreover directed to file affidavits

to ascertain the extent of compliance of the directions issued in the aforesaid

decision of the D.K.Basu case.

Q. What was the relief given by the Court to the victim concerned?

A. Compensatory relief was given. The Supreme Court has declared

that where the infringement of the fundamental right is established, it

cannot stop by giving a mere declaration. It must proceed further and give

compensatory relief, not by way of damages as in a civil action but by

way of compensation under the public law jurisdiction for the wrong done

due to the breach of public duty by the State in not protecting the fundamental

right of the citizen. This is a progressive approach as civil action for

damages is a long drawn and cumbersome judicial process and most often

the victim or the family of the victim is not in a position to undertake

such a venture.

Q. Is there not a corresponding need to create awareness of fundamental

human rights among police officers themselves? Has the Indian judiciary

responded to this need in any way?

A.The need of the hour is undoubtedly to train and re-orient

police officers in this respect. The Court has frequently made reference

to this fact. Interestingly enough, there has also been reference to the

fact that it is crucial that training be given in this respect not only

to police officers but to members of the lower judiciary as well who deal

with these issues on a day-to-day basis.

In a recent decision ( In re M. P. Diwedi, [(1996 )4 SCC), the Supreme

Court took serious view of a Magistrate not taking action for removal of

handcuffs of under-trial prisoners brought before him. The Court noted

the complete insensitivity of the Magistrate to this serious violation

of human rights of under-trial prisoners and recorded strong disapproval

of his conduct and directed that this disapproval of the court be placed

in the personal file of the Magistrate.

Q. Sri Lanka and India face similar problems in the area of custodial

violence. What would you see as the most pressing need to address these

problems right now?

A. Unless the directions and requirements laid down by apex courts

trickle down to the lowest levels of judiciary and enforcement authorities,

the protection of the human rights of citizens will remain a dead letter

of law. As far as India is concerned, it is imperative that the Central

and State Governments, National Human Rights Commissions, the Judiciary,

Media and the Non-Governmental Organisations should make a sincere and

concerted effort to create mass awareness of basic human rights. Awareness

is thus the key to this whole issue. Creation of that awareness together

with provision of the necessary support for a victim to go before the courts

and highlight the wrongs done to him or her remains a priority.

Sermons won't make this wrong right

By K.M.B.B. Kulatunge, President's Counsel, Retd. Judge of the Supreme

Court.

The observance of human rights rather than

its theory is vital to the well being of the people. Over emphasizing theory

as against practice of human rights can create contempt for the concept

itself, even if fundamental rights are entrenched in the Constitution.

It is my impression that in Sri Lanka,we have been inclined to make

human rights education elitist by engaging in endless "sermons without

giving sufficient consideration to the ground situation at grassroots level."

I

am writing this article to bring about a change of attitude in those who

are interested in the advancement of fundamental rights and freedoms. There

are two significant features that characterise 50 years of independence

in Sri Lanka. I

am writing this article to bring about a change of attitude in those who

are interested in the advancement of fundamental rights and freedoms. There

are two significant features that characterise 50 years of independence

in Sri Lanka.

First, for about 40 years, the country has been under Emergency Rule,

second, fundamental rights have been entrenched in the 1972 and 1978 Constitutions

for 26 years during which period also there has been extensive rule by

Emergency Regulations.

From 1989 to April 1996 during my tenure as a Judge of the Supreme Court,

I handed down 210 judgements of which 110 related to fundamental rights

complaints in which relief was granted. Thirty of them were infringements

of the rights to freedom from torture and the freedom from unlawful detention

and/or arrest. The other cases involved mostly violation of the right to

equal protection of the law. I presume that my brother judges also handed

down a large number of such judgements. It would appear however that even

after the change of administration in 1994, the incidents of violations

of fundamental rights have not ceased. Judgements of the Supreme Court

have found police officers guilty of torture and unlawful detention. The

above observations are made purely on the basis of decided cases. Moreover,

it has to be noted that all such violations are not brought before the

Supreme Court in view of the fact that there are many victims who have

neither the means nor the resources to do so.

Consequently, the incidents of violations of fundamental rights may

well be much more than what the decided cases indicate. The most basic

and important human rights contained in the Human Rights Covenants acceded

to by Sri Lanka were entrenched in the 1972 Constitution.

There was no express provision in that Constitution vesting jurisdiction

in any particular court to adjudicate on complaints of infringement of

fundamental rights. However, it is my view that the fundamental rights

entrenched in the 1972 Constitution were enforceable in the sense that

a violation of such a right could be made the legal basis for seeking appropriate

relief from the original or appellate courts.

The 1978 Constitution also entrenched fundamental rights (except the

right to life) and vested exclusive jurisdiction in the Supreme Court to

hear and determine complaints of infringements of those rights by executive

administrative action. Violations purely attributable to private persons,

corporate or incorporate, have to be adjudicated upon in the first instance

presumably by the original courts.The questions that have to be asked now

are whether there is any material difference between the present situation

where upon the proof of an infringement of a fundamental right, specific

relief is available and the period when no such relief was available?

Were human rights safeguarded by common law and by statutes even during

that period? Was the evidence of violations of human rights prior to 1972

as high as it is in modern times? If not, what is the cause of regular

and persistent violations of human rights which is the current experience,

despite the entrenchment of human rights in the Constitution? Some observations

made by Sir Ivor Jennings who drafted many of the provisions of the Soulbury

Constitution are pertinent here.

Advising against the inclusion of a Bill of Rights in the Constitution,

he said that " In Britain, we have no Bill of Rights: we merely have

liberty according to law, and we think - truly, I believe - that we do

a job better than any country which has a Bill of Rights or a Declaration

of the Rights of Man" ( Approach to Self Government ( 1958 ) pg 20

)

The Soulbury Commissioners themselves believed that fairness in the

administration specially as regards minority rights could best be left

to the good sense of the majority community as a matter of trust, subject

however to the Constitutional safeguards specified under Sec. 29 (2) of

the Soulbury Constitution.

This approach clearly emphasised the importance of the observance of

human rights as against mere entrenchment. It is significant also that

the provisions guaranteeing rights in relation to religion and equality

and equal protection of the law (Sections 29 (1), (2), and (3) ) were made

before the Universal Declaration of Human Rights ( 1948) and the International

Covenants on Human Rights (1966).

The said provisions were directed to safeguard the minorities. Jennings

explains that "......a minority is not necessarily a racial minority.

It may be based on race, caste, religion, economic interest or pure politics

which were in Ceylon important for election purposes" (" Constitution

of Ceylon" Jennings Pg 44) While Section 29 of the Soulbury Constitution

thus safeguarded the rights which were apprehended by the minorities as

threatened rights, there were also many statutes which protect all the

core rights which have been since then entrenched in human rights treaties.

Some examples would be the Abolition of Slavery by Ordinance No 20 of 1844,

the Police Ordinance of 1865 which required a suspect to be produced before

a Magistrate within 24 hours of his arrest, the Penal Code No 2 of 1883,

the Criminal Procedure Code of 1898, the Trade Unions Ordinance of 1935

and the Prevention of Social Disabilities Act of 1957.

Several judicial decisions of that era also articulated these same core

rights as in King Vs Thajudeen where it was opined that violence

by a police officer ought to be severely punished, the Bracegridle case

where the Rule of Law was upheld when it was held that the Governor's order

for deporting Bracegridle was invalid as the precondition for such an order,

namely a state of emergency did not exist, Muthusamy Vs Kannangara and

Corea Vs the Queen where it was held that a suspect is entitled to

be informed of the reason for his arrest and that the failure to do so

renders the arrest unlawful. In re Wickremesinghe where it was held that

judges and courts are open to criticism provided that nothing is said that

scandalises the courts by acts calculated to impair the administration

of justice, Queen Vs Tennekoon Appuhamy where it was held upon finding

that the accused had been subjected to torture and cruel and inhuman treatment

by a police officer, that the latter's conduct called for " a full

dress inquiry by an independent tribunal" and Sunthralingam Vs

Inspector of Police, Kankesanthurai where it was held that the prevention

of a low caste Hindu from entering a place of religious worship was an

offence under the Prevention of Social Disablities Act.

In the background that I have described above, the Soulbury Constitution,

with the separation of powers between the legislature, the executive and

the judiciary and with the safeguards in Section 29, provided an ideal

foundation for the establishment of a secular state and a democratic system

of government. This was however, not achieved because the Westminster system

of government based on one party rule is singularly unsuited in a multi

ethnic, multi religious third world country. From the inception, the government

was predominantly Sinhala and the participation of Tamils or Muslims was

possible only if they joined a Sinhala Party or by the grace of the party

in power. Jennings drafted the 1946 Constitution according to the British

traditions. So, he cannot be blamed for failing to provide power sharing

in the executive government at the centre.

On the contrary, we must blame our leaders for their parochial attitudes.

What is more, two further measures paved the way for the current disorder,

including human rights violation in Sri Lanka. Firstly, it was the Citizenship

Act which disenfranchised a large number of persons of Indian origin who

had exercised franchise since 1931 leading to future governments having

to take legislative action to correct the injustices so inflicted. Secondly,

it was the language problem. If Sinhala and Tamil were compulsorily taught

in schools after Independence, any citizen of whatever race would have

been competent and eligible to assume any office in any part of the country

on the basis of equality. Instead, the UNP and the SLFP both hastened to

make Sinhala the official language in their rivalry to gain votes.

This gave rise to a counter campaign by the Tamils, communal riots ,

disorder and Emergency Rule. While there is no objection on my part to

the entrenchment of fundamental rights in the Constitution, I feel that

such entrenchment in the 1972 and 1978 Constitutions as well as the accessions

to the 1996 International Human Rights Covenants and the First Optional

Protocol to the ICCPR were political gestures wittingly or unwittingly

designed to act as a palliative to the injustices committed by successive

administrations. We have failed to understand the true issues affecting

Sri Lanka. The two main Sinhala parties, on the other hand, have had the

monopoly of government power and each party when in power would discriminate

against its opponents, setting the wrong example to the administrative

services.

My conclusion is that the government at the centre has been politicised

by the enthronement of one party rule, the public service has been politicised

since 1972 by the conferment of wide political rights on the public officers

and local government has been nullified by political interference on the

basis of party, depending on which party is in power.

Until this system is replaced by a system where all communities become

sovereign partners in a sovereign government and cultural integration is

established by abolishing the language barrier, the present disorder will

continue and violations of human rights will increase despite constitutional

provisions safeguarding such rights. Mere discussions and political deliberations

will not bring about any improvement in the current situation.

JUDGMENTS

FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS

Edward Oswald Bennet Rathnayake Vs The Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation

and Others

SC Application 867/96

Before Fernando J.

Wadugodapitiya

J.Gunewardene J.

Decided on 11th June 1998

Article 12(1)/ powers conferred on statutory bodies in respect of

telecasting on the airwaves so conferred in trust for the public and should

be exercised for the benefit of the public/ a fair and objective procedure

should govern the selection process of telefilms for telecast during primetime.

Facts

The Petitioner who was an established telefilm producer complained that

the refusal of the Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation ( SLRC ) to telecast

a Sinhala telefilm titled "Makara Vijithaya", produced by him

at a cost of 2.3 million during "prime time" was a violation

of his fundamental rights under the Constitution.

He went on to ask for a declaration that the procedure leading up to

the refusal of prime time was in violation of Article 12(1) for want of

a fair and objective selection procedure, including criteria announced

in advance, for compensation and for direction to the SLRC to prescribe

and publish the criteria for selection of teledramas for telecast during

prime time and to set up an independent and competent review panel to determine

whether telefilms ( including "Makara Vijithaya") met those criteria.

Held by Mark Fernando J. ( with Wadugodapitiya J. and Gunewardene

J. agreeing )

That the Respondents have failed to show that the members of the preview

board, the appeal board and the "supreme appeal board" that viewed

" Makara Vijithaya" and rejected it as unsuitable for prime time

viewing had been duly appointed. The 8th Respondent Chairman and the 5th

7th 9th and 12th Respondents were held not only to have acquiesced in the

violation of their own established procedure but to have purported to review

the film themselves, thereby usurping the functions of the independent

"supreme appeal board"

It was further held that the powers which a statutory body like the

SLRC has in respect of television and broadcasting are much greater than

in the case of other media like the print media, because the frequencies

available for television and broadcasting are so limited that only a handful

of persons can be allowed the privilege of operating on them and those

who have that privilege are subject to a correspondingly greater obligation

to be sensitive to the rights and interests of the public.

The airwaves are public property and the State is under an obligation

to ensure that they are used for the benefit of the public.

The powers conferred on the 1st Respondent ( and its directors and officials)

in respect of telecasting on the airwaves were held to be so conferred

in trust for the public and had to be exercised for the benefit of the

public, for which purpose it was obliged to establish and implement a fair

and objective procedure to determine whether a telefilm submitted to it

was suitable for screening, and if so the time of screening.

That obligation was held to have been seriously violated in the instant

case.

Court granted the Petitioner a declaration that his fundamental rights

under Article 12(1) had been violated.

The decision of the Board of the 1st Respondent in respect of the film

"Makara Vijithaya" was quashed and the 1st Respondent was directed

to submit the telefilm for final review- after specifying the applicable

criteria- by the "supreme appeal board" within a month of the

deliverance of the judgement. Having taken into consideration the considerable

financial loss suffered by the Petitioner which was aggravated by the delay

of the Respondents to deal expeditiously with his appeals together with

their evasive responses to Court, the denial of the opportunity to the

Petitioner to telecast his film outside prime time by the Respondents not

replying his query as to the available time belt and the manner in which

the Respondents had acted in deliberate and cavalier disregard of their

own rules, the Court went on to award the Petitioner a sum of Rs 1,000,000/=

as compensation payable by the 1st Respondent on or before 30/06/98 with

further interest calculated at a rate of 24% p.a. in the event of delay.

The 2nd and the 8th Respondents were ordered to personally pay a sum

of Rs 7,500/= each as costs and a similar order with regard to costs was

made in respect of the 5th, 7th 9th and 12th respondents in the sum of

Rs 2,500/=

The SLRC was also directed to give publicity in all three languages

on its own television channel to the procedure and criteria for the selection

of telefilms for telecast during primetime and outside, distinguishing

as necessary between different types of telefilms.

The telecast was directed to be made between 7.00 p.m. and 8.00 p.m.

at least once every month from July to December 1998 and thereafter whenever

the procedure or criteria are amended.

|