|

13th December 1998 |

Front Page| |

| Villagers

of Noraichcholai are determined to stop the controversial coal power project.

Feizal Samath reports

People powerWatching his wife and two children tending their vegetable garden in Sri Lanka's northwest coast, Christopher Tissera hobbles around with a stick to support his leg, wounded in police firing last year. "I don't do any work anymore, sir. It is my wife who manages the farm and the household with our two children," says the 42-year-old farmer of Noraichcholai village in the Puttalam district. Tissera vividly remembers the day he was shot. On April 25, 1997, he and his wife Sumana, had finished the day's chores on their 1.6-hectare farm and gone to town to buy the daily requirement of 18 litres of kerosene needed to work the water pumps.I saw a crowd gathered there and a lot of police around. Out of curiosity, I moved closer and then suddenly there was firing. I fell bleeding from the side," he recalls.

Noraichcholai, a quiet coastal village whose residents - mostly Roman Catholics and Moslems- are involved in vegetable farming, fishing and government jobs, lies about 15 km west of Puttalam town and about 120 km from Colombo.

The plant includes a four-km jetty stretching out to sea from the beach and a landing bay, which would require round-the-clock security. The plant in addition to instantly being added on the rebel list of potential economic targets, would also endanger the village. "Look at this _ The plant becomes a target. Our village becomes a target. The whole place becomes one hell of a security zone. The freedom of movement is going to be restricted. We would be restricted in cultivating our lands. Our livelihood would be affected," said an angry Fernando, who owns up to 30 acres of vegetable land. The fears are valid and whatever the government says, one cannot detract from the position that a coal power plant of this magnitude would justify top security, which in turn would affect people's movements and their jobs. "Look at Cinnamon Gardens in Colombo . you have to show the identity card to go to your home," argues Fernando. One need not be a health or environmental specialist to question the hazards, a plant of this type may pose. In fact, sediment from the Puttalam cement factory, formerly owned by a state agency and now run by a private firm, which has been in operation for over 30 years, settles on plant life affecting the process of pollination. A police post has been set up near the beach site of the proposed coal plant, which abuts flourishing vegetable plots and a small fishing settlement, but work appears to have been suspended temporarily. "According to our information, the Overseas Economic Cooperation Fund which is providing a Japanese yen loan for the project has got cold feet after the protest and the project appears to have stalled for the moment," said Ivan Peter Fernando, a Roman Catholic priest and director of a church-funded local NGO. Officials from the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB), responsible for the plant, concede there is a slowdown in progress due to local opposition. There was no independent confirmation from Japanese authorities over the delay. Sri Lanka has a total installed power capacity of 1,564 megawatt through a combination of hydro and thermal power generation, and the government says the demand for electricity is rising by 10 percent each year. What has angered residents most is the devious way the authorities launched the project. A few weeks before April 1997, government surveyors were seen measuring the area and residents were told it was for road expansion project. "They came a few more times and gave different excuses such as a development project - all the time hiding the truth," said Peiris. It was around mid-April that the people discovered what was happening and chased away the surveyors, after threatening to beat them up. Tensions rose as CEB trucks and vehicles driving through the village were stoned or the road obstructed by trees felled by residents. Police and security forces also searched the entire village on one occasion. CEB chairman Arjun Deraniyagala has said the project costing 300 million US dollars will go on, and argues that residents' fears are misplaced and that they are misguided by non-government agencies opposing the plant. He says environmental pollution would be minimal. Pro-plant backers, claim it was NGOs who instigated the people's protest movement. To some extent it may be true, in the context of understanding the ramifications of environmental and health hazards, etc. Residents like Fernando were at the inception more concerned about losing their land and the devious methods used to launch the project. The environmental and health issues came later when the NGO lobby got activated and with renewed interest, about the pros and cons of coal power, etc. But if residents are unaware of environmental and health problems, shouldn't they be told? And in this case, apart from the usual suspicious manner that government agencies go about their business, the repercussions would impact on their lives. Ironically, this is the third site for this station after similar people's protest movements saw it being abandoned, first in the eastern town of Trincomalee in around 1993 and then in the southern town of Mawella in Hambantota district. The fight against the plant follows in the wake of other people's movements springing up in other areas in Sri Lanka as residents fight bitterly to protect their land from development that is seen as uprooting communities or hazardous to the environment. The project cost was also cut from an estimate of 500 million US dollars at Mawella, another cause for alarm. "There is a lot of suspicion about the project and the way it is being done," argues Saheed Mubarak, social activist and long-time resident of Puttalam. "It has been lying and cheating all the way," says Mubarak, a former civil servant, who has collected loads of documents and data on the project and its impact on the land and people and leads the protest on behalf of non-governmental agencies.Mubarak says Puttalam district, and Noraichcholai in particular, is a thriving agriculture region which accounts for more than 40 percent of the country's onion output and a bulk of the island's fish requirements. In addition, many varieties of vegetables, including potato are produced here. Potato is normally grown in hilly and cold areas. The area also produces salt and has dozens of coconut plantations. "This region is rich in agriculture and no one is idle. There are jobs for everyone. The people are very industrious and have little time for anything other than work. They are trying to force this plant on us, which they could not do in other areas where there are more aggressive populations," he said, producing files and documents to prove his case. Driving through the village one is struck by the lush green fields where men and women, are either sprinkling water on rows of onion and chillie or uprooting sweet potatoes. Mubarak says waste water and coal ash from the plant would pollute the environment and also destroy sea life. He rejects the government assertion that the plant is being built on unused land, saying "one must go to the site to find out who is speaking the truth." Water is available in plenty at the beach site and is not salty, unlike many other coastal areas in Sri Lanka and the success of a few vegetable farms near the site proves that anything can be grown there. |

||

|

Front Page| News/Comment| Editorial/Opinion| Business| Sports | Mirror Magazine |

|

|

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to |

|

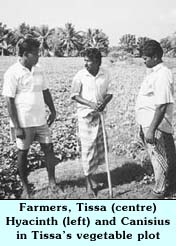

Farmers

Canisius Peiris and Hyacinth Fernando like others are law-abiding citizens,

but the controversial coal power project has stirred the passions and anger

of the village and determined residents are prepared to do anything to

stop its implementation. "We won't allow them to dump rubbish at our

doorstep," says a determined Peiris, secretary of a residents group

opposing the plant. His neighbour, Fernando agrees: "Just because

we are a peaceful community, they think we are meek and can force anything

down our throats."The community of about 10,000 people in Noraichcholai

and other outlying villages is perturbed over plans to build the 900-megawatt

coal power plant, which the government says will provide about 25 percent

of the country's power requirement by 2004. Fears are justified and questions

abound about potential environmental and health hazards, families being

evicted from their land and settled elsewhere and the creation of a security

zone that would seriously affect the movement of residents. A security

zone in and around Noraichcholai is a distinct possibility in view of the

Tamil rebel threat. Already kerosene is rationed to resident farmers by

government authorities, fearing the fuel would fall into the wrong hands.

Kalpitiya, a few kilometres away, has a major navy base to deter attacks

on fishing villages by the rebels, which have happened in the past.

Farmers

Canisius Peiris and Hyacinth Fernando like others are law-abiding citizens,

but the controversial coal power project has stirred the passions and anger

of the village and determined residents are prepared to do anything to

stop its implementation. "We won't allow them to dump rubbish at our

doorstep," says a determined Peiris, secretary of a residents group

opposing the plant. His neighbour, Fernando agrees: "Just because

we are a peaceful community, they think we are meek and can force anything

down our throats."The community of about 10,000 people in Noraichcholai

and other outlying villages is perturbed over plans to build the 900-megawatt

coal power plant, which the government says will provide about 25 percent

of the country's power requirement by 2004. Fears are justified and questions

abound about potential environmental and health hazards, families being

evicted from their land and settled elsewhere and the creation of a security

zone that would seriously affect the movement of residents. A security

zone in and around Noraichcholai is a distinct possibility in view of the

Tamil rebel threat. Already kerosene is rationed to resident farmers by

government authorities, fearing the fuel would fall into the wrong hands.

Kalpitiya, a few kilometres away, has a major navy base to deter attacks

on fishing villages by the rebels, which have happened in the past.