|

22nd March 1998 |

Front Page| |

Village of Forgotten HeroesCaring for them is the responsibility of the whole of society but society doesn't know about these people, and there is no need to preach to these people about the costs of war - they are living examples of it. By Delon Weerasinghe

Ranavirugama is a small village in Wathupitiwela off Nittambuwa. It looks like any normal village, but life for those here holds many challenges that might not be obvious to the casual observer. Ranavirugama is home to 111 families of soldiers killed or disabled in the war. The war might be far away, but these people battle every day to lead normal lives. The opening of the pre-school stands as a sad testimony to how alone they are in this battle. The pre-school was first inaugurated by the President, but soon it faced problems because of a lack of teachers. The School had to close down and all the children were enrolled in schools outside the village. The problem of teachers was the main reason the school could not be revived, until one of their own came up with a solution. Sunandi Perera is the sister-in-law of C. G. S. Chandrasekera, a resident of Ranavirugama, who lost his left leg to a landmine. She resigned her job as a teacher in Colombo in order to open up the Ranavirugama pre-school. With little help she, along with her sister and the Village Welfare Society finally saw all their hard work pay off. The pre-school reopened on the 15th of January with four students. Even though the number of students is small, the villagers express optimism, as there are more than 30 children in the village of pre-school age, and the numbers are sure to grow. It is probably just as well that there are so few students, as the school has very little resources. But despite these problems there is a determination amongst the people that they will not let the school close down again. They believe that their unity will see them through. "We are very united - for anything" says Santha Fernando. Santha Fernando is the Secretary of the Village Welfare Society. He does not have his right leg. "I joined the Army in 1985,' he explained. "In 1990 I was stationed in Palaly. One day during operation Jayashakthi, we attacked an LTTE camp in Myladi. I lost my leg when I stepped on a 'batta' that had been planted near one of their bunkers". His story is like that of many others in the village, a majority of whom have lost limbs to landmines. There are others who have lost both legs, others who are paralyzed, still others who are deaf and some who are blind. Women play a very prominent role in Ranavirugama. Because of their husbands' disabilities the women find themselves forced to take on a bigger workload. Some men are so severely disabled that they need to be fed, dressed and taken to the toilet. Ranavirugama is no idyllic retirement village for disabled soldiers. Even though disabled soldiers are entitled to retire, there are some who have not. They travel daily to their posts at Colombo and Panagoda. The main reason they opt to stay in the Army is financial. A soldier who cannot complete 12 years of service due to disability, is entitled to his salary upto the age of 55, and a disability pension afterwards. Whereas, those who complete 12 years are entitled to their salaries up to 55, and a regular pension. A disability pension is smaller than a regular pension. And so those who can, try their best to complete their 12 years. Ironically, it is the very people who will have to live off a disability pension, who will need the money most as they get older. Some villagers who tried to become self-sufficient have suffered serious setbacks. They bought three-wheelers using compensation of about Rs 60,000, they got from the Army, in order to make a living. They had the rest of the cost financed. "But the three -wheeler drivers in the area did not allow us to use any of the parking lots and threatened to assault us if we tried". Despite these threats, the ex-soldiers decided to stand their ground and finally won the opportunity for one of their three-wheelers to use the Park. But this was a hollow victory for them as there are about 15 three-wheel owners in the village. These lie dormant, with their owners paying heavy costs, but being unable to make any money from them.

On the other side of the village playground is the Wathupitiwela Hospital. A partially collapsed wall separates it from the village. "That is the Hospital mortuary," says Fernando, pointing across the playground to the nearest building. The hospital, he says, regularly disposes of human remains in shallow holes dug behind the mortuary building, despite there being a cemetery only a short distance away. "Sometimes dogs dig up these remains and drag them over here" he says. The wall was ordered to be built by a politician who was horrified to find the body of a young child haphazardly buried in a shallow grave. But the wall collapsed a few months later. Residents of Ranavirugama face many problems with infrastructure. The water supply system for the village was donated to them by the Water Supply Board. They constructed a large water tank to be filled by a tube well. The power supply for the pump was obtained under the name of the Water Board, which is classified as a Company by the Electricity Board. Therefore, the villagers are required to pay electricity bills on the same basis as a big business company in order to obtain water. As a result, they pay huge amounts for the electricity used to pump water, than they do for the electricity used by the entire village. The Electricity Board says that they can have their bills significantly reduced if they change the classification under which the supply is registered. This will cost the villagers Rs 20,000, and they do not have the money. Street lamps are a necessity say villagers. Several houses in the village had been burgled, with thieves taking everything - even the bag of rice. "We take off our artificial limbs before going to bed" explained Fernando, "so if the thieves break into our houses, by the time we get our legs back on, they have enough time to stop and give us a salute before running off". He hopes that street lamps would discourage would-be thieves. Ranavirugama residents appear helpless. They are not well informed as to how they could get help from their local authorities, neither is there an official army representative in the village to see to their problems. A special army team that visits the village once a year makes official inquiries into the shortcomings of the village. This team makes a report to the army's Directorate of Welfare. The Directorate then follows up by contacting the civil and local authorities concerned. As conditions in the village testify, this cannot be considered a very effective process. Major General (Dr) C. Thurairajah a high-ranking officer in the army medical corps, which also sees to the welfare of disabled soldiers, says that the army has done a lot of soul-searching on the subject of disabled soldiers. He feels that it is not fair to point a finger at the army, as the village is a civilian one and many of the problems they face need to be dealt with by civil authorities. Another officer in the medical corps agreed with him saying, "lt's not the responsibility of the army - the army can't fight a war and take care of their disabled. You can't tax an institution to do two things at once." He pointed out that taking care of all the needs of these people would cost a lot of money, and that the army had many pressing costs with the war. "Caring for them is the responsibility of the whole of society" he says. The fact that they are disabled, or the fact that they became disabled fighting for their country, does not get them much consideration or respect say villagers. Some, like the three-wheel drivers, are even outright opposed to them staying there. Life is not easy for these "Ranaviruvo" . Society owes them respect and help in their problems, which could very easily be dealt with, if proper initiative is taken. Local authorities especially should sit up and take notice of their grievances, since most are due to bureaucratic bungling. Simply shoving the war disabled into a corner and naming it Ranavirugama is not enough. |

||

|

More Plus * Hope for the hopeless

Front Page| News/Comment| Editorial/Opinion| Business| Sports | Mirror Magazine |

||

|

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to The Sunday Times or to Information Laboratories (Pvt.) Ltd. |

||

There

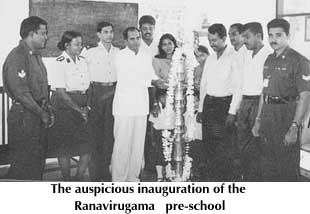

were many wor- ried faces as the aus picious time drew near. The chief

guest had not yet arrived. The traditional oil-lamp had to be lit at 10:10

a.m. for the auspicious inauguration of the Ranavirugama pre-school. The

time came, and the honour fell on an army medical team, which had shown

up purely by coincidence to conduct a clinic in the village. The invited

chief guest, the President's Coordinating Officer for the Gampaha district,

never showed up.

There

were many wor- ried faces as the aus picious time drew near. The chief

guest had not yet arrived. The traditional oil-lamp had to be lit at 10:10

a.m. for the auspicious inauguration of the Ranavirugama pre-school. The

time came, and the honour fell on an army medical team, which had shown

up purely by coincidence to conduct a clinic in the village. The invited

chief guest, the President's Coordinating Officer for the Gampaha district,

never showed up. The

small houses the villagers live in do not have kitchens. As a result, cooking

has to be done in the living room, making it impossible to use firewood.

The higher cost of using gas for cooking does not make it a very attractive

option, but many villagers see no choice. The alternative favoured by the

villagers is to add a small kitchen to their houses, but where is the money

? Neither can they get a Bank mortgage, because they still haven't received

the Deeds to the houses they live in. They are even more concerned by this

because large cracks are now appearing on the walls of some houses.

The

small houses the villagers live in do not have kitchens. As a result, cooking

has to be done in the living room, making it impossible to use firewood.

The higher cost of using gas for cooking does not make it a very attractive

option, but many villagers see no choice. The alternative favoured by the

villagers is to add a small kitchen to their houses, but where is the money

? Neither can they get a Bank mortgage, because they still haven't received

the Deeds to the houses they live in. They are even more concerned by this

because large cracks are now appearing on the walls of some houses.