![]()

Though it is difficult to decide whether "Fire" is a movie that is exploitative or not, its not difficult to say that it has an alternative approach, like some 90's version of Herman Hesse's "Siddhartha'' for instance. Admittedly the comparison with "Siddhartha'' can be due to an association of ideas, because of the abundance of swamis and the simmering sexual intensity that hides behind both movies. But "Fire'' also comes out of the new post Rao- liberalised, India which easily interchanges between religious men and Western home videos.

The movie also has a quirky "My Beautiful Launderette'' quality and that is not just because the storyline is about female homosexuals. (Laundrette by Hanif Quereshi was about gays.) But since the story is also not about some hip lesbian couple but about a disillusioned pair of sisters-in-law, it can, even at the worst of times pass for a social commentary on the female condition in predominantly male chauvinistic societies.

India at heart is liberal, though a grid of conservatism runs through

the country and therefore its not difficult to think that a plot like this

could really materialise in some throbbing Indian suburb. There is no absolute

difference between the swami worshipping husband of Radha and the Kung

Fu worshipping husband of Sita who are both insensitive chauvinists. In

vast teeming India, this is probably the kind of story that exists in real

life, though probably only a fraction of the suppressed women actually

turn into lesbians.

This is not a story of lesbian chic however and anybody going into the movie for cheap male thrills and titillation will be hit on the face like any chauvinist should be. Its a story well told, and though the sapphic plot is undoubtedly offbeat and is of substantial novelty value, its certainly not the substance of the movie.

In a way, movies have to move away from the tired threadbare beaten art flick genre and explore new themes in new and changing places. Satyajith Ray cannot exist everyday, and the art of serious moviemaking has to change.

It has to take into consideration the new India, the MTV generation and the changing mindsets of a vibrant youth culture that is pulsating and vibrant, even though perhaps very superficial.

All of English language creativity in India seems to be a copy of Hollywood and American magazines, so its almost funny to watch scenes edited in a way that they look and sound like they came straight out of the Hollywood studios. But that is part of the authenticity of the work as well, because the sort of culture depicted in the film is a hybrid, and at the core now very Indian.

Also refreshing about "Fire'' is that there is no excess or overstatement in it unlike some of the new "message'' movies that come out of the sub continent which are melodramatic and mushy. Characters like Radha and Sita move with an easy pace, speaking in homespun idiom. The scenes direct from the kitchen for instance with papadam on the frying pan and sexual expectancy (illicit) in the air, are happily true to life because they haven't been embellished by artificial cinematic devices.

Why haven't more of these sort of contemporary movies come out of this part of the world ? Stereotypes that have been associated with the art movie may have imbued directors with some preconceived notion of what serious movies should look like.

All such illusions may have been cast aside in "Fire'' but also germane is how much the inherent voyeuristic value of the subject of lesbianism has got to do with the novelty of the movie.

These are times when international newsmagazines such as "Newsweek'' run cover stories about lesbianism, claiming that there is some new discovered chic about the whole condition. What is probably true is that everybody including ''Newsweek'' cashes in on the value of the subject as a reader turn on. Therefore the exploitative nature of having a soft pornographic subject as a central theme in a movie cannot be totally discounted. Yet "Fire" does well, as the story is about the problems of neglected Indian wives, as much as it is about lesbian women.

The Fire begins with the honeymoon scene in Agra, with the grumpy groom and a vibrant and young bride, with the Taj in the background Something seems to be wrong.

"Don't you like me? she asks.

Something is wrong.

This discord sets off the trigger of change, in the extremely conservative joint family, which eventually leads the two women to develop a lesbian relationship and…things fall apart. That outlines the story. But Mehta has more than that behind the screen.

Fire's connection with Indian tradition is primordial. Fire is talked about in the Vedas and in the Puranas, and occupies an integral part in the daily life of an average Indian. Agni is the supreme purifier and a symbol of purity. Hence the ideal woman in the Indian patriarchal psyche too is always likened to fire.

The fire becomes the main symbol in the film. The other being Biji- the ailing mother. It is the presence of the fire that makes an otherwise universal theme very much Indian. It is the fire that links the family to the myths of India.

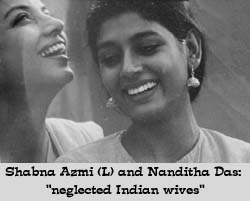

The names are very suggestive. The wife of younger brother who carries on with the Chinese hair dresser Julie, is named Sita (Nanditha Das), one of the extreme examples of the Indian ideal woman. The real Sita of Ramayana is the wife of a steadfast husband or ehapathni virathan, Rama. On the other hand the wife of the conservative and pious elder brother is called Radha (Shabna Azmi), who in the myths is the consort of Krishna. Krishna is the playboy of the Indian myth (at a narrative level, not at the theological level.)

At the end of Ramayana Rama asks Sita to do an Agni Pravesam to 'test' her chastity, as she was in Ravana's custody for a long period. When she emerges from the fire successful he banishes her. Total disregard for her feelings, her desires and more than anything her love for him. These myths are inverted, or rather subverted, in the film. It is Radha who goes through the test of fire at the end of the film (very cleverly done by the director as an accident). This delivers her into a new life with her new partner.

The mantra of the film perhaps is "I desire." Desire is the cause of all… evil, says the swami, who suffers from hydrocele. Remember, the Waiting for Godot, character?

"I desire to live. Without desire there is no life. Without desire there is no world, I desire her love, I desire her warmth, I desire Sita's body," says Radha. D. H. Lawrence said somewhere in the Plumed Serpent "America can never die, because it never lived."

The driving force here is the desire to live, to feel the various passions, which she was denied in her married life. She was just another object in the house revolving around her husband, who is an aspiring Gandhi, who wants to control his desires, thereby denying Radha's right to sexual experience. "If you want to experiment, do it with the swami," Radha retorts to the astonishment of her husband, and the audience at the end. She is a victim of traditional values. So is Sita. So is Sita's husband. So is Mundu, the domestic.

Biji the handicapped mother-in-law emerges as a symbol of the dying, handicapped, outdated, traditional value system which exists at the mercy of the younger newer generation which upholds a different set of values. In the last scene Biji appears amidst the flames fallen on the floor. While Radha desperately struggles to put out the fire, Biji is taken care of by Radha's husband.

Fire highlights how the traditional values ignore the basic human instincts. Mundu has no way of expressing his repressed emotions. His only emotional outlet is to watch triple X videos and masturbate; all the while Biji is watching. He has no choice because the TV set is in Biji's room.

While Mundu resorts to his own way of pleasures Sita and Radha develop a relationship that is a taboo in such a milieu. The relationship goes beyond the emotional bonding. They engage in sex. They discover the pleasures of sex through each other's passions which their husbands denied them. Whether they are biological lesbians or casual lovers is not clear.

At the end of the film a host of questions beg for answers. Was it Sita's revenge on the family? Does Sita really grow up from the young girl who giggles at swami's illness, to a mature woman who can lead Radha, into an unknown world? Radha goes searching for the new, but can she trust Sita, because Sita herself is not sure about her feelings? Immediately after the first lesbian encounter between the two Sita asks "Did we do anything wrong? No, says Radha.

Each frame tells you more than the dialogue does. In the last scene, where Radha's saree catches fire, and her husband stands shocked at the new incarnation of his wife, in the background hangs the board "Home Sweet Home".

The music is evocative but Rahman could have done better. The actors too need to be commended. Their eyes tell you a million things.

The film deals with one of the pet topics of the times, the conflict between the tradition and the modern, between what was India and the West. Writers like Chinua Achebe, Arundathi Roy dwell on the same theme, while Gam Peraliya was the Sri Lankan parallel. It is a poem. A poem of burning emotions beautifully captured in carefully planned frames.

Continue to Plus page 8 * Medical Measures

Return to the Plus contents page

![]()

| HOME PAGE | FRONT PAGE | EDITORIAL/OPINION | NEWS / COMMENT | BUSINESS

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to

info@suntimes.is.lk or to

webmaster@infolabs.is.lk