From watta to high-rise: Community building in a diverse society

Multiple identity groups and diversity are fundamental features of contemporary cities. However, do differences and multiple identities pose a barrier to building strong communities? We constantly promote western examples or look to our much beloved ‘Singapore’ model for urban planning and multicultural community building. It is often believed that the state and a strong political apparatus should provide an impetus for urban development and community building.

This article, however, draws inspiration for communities from a different quarter: Colombo’s urban watta communities relocated into high-rises under the Urban Regeneration Project and illustrate how these communities are organically heterogeneous and engage in community building.

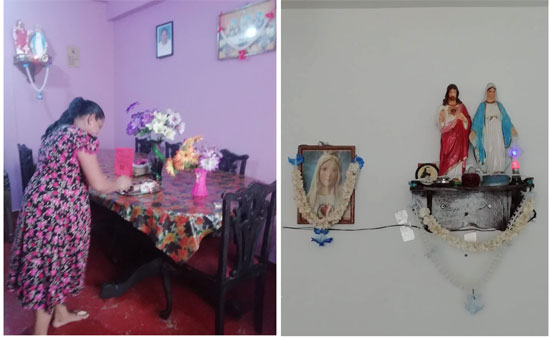

Room for religious ritual: An important part of community and personal life

Urban wattas in Colombo are relatively different to the highly concentrated favelas, bastis and sprawling slums in other countries, and are more evenly distributed across Colombo. Wattas possess a complex social structure and are based on family and kinship, ethnicity, religion, political affiliations, charismatic community leaders, drug networks, livelihoods, and spatial dynamics. The URP-led relocation of wattas has created disruption in previous community networks. While some watta communities were broken up and put into different flats in the post-relocation stage, others were relocated as a whole. Despite being broken up into different floors in the high-rises, these communities do not remain broken forever. Many communities are forged based on earlier watta networks, and more often the creation of new communities takes place, this time based on new spatial dynamics like floor-centric communities.

As a social anthropology student, much of my time was spent “hanging out” with people, engaging in everyday life, attending religious rituals, participating in birthdays, puberty ceremonies, funerals and other community events to explore their interaction with these places and the significance of these places for home and community life. In addition to my household survey, initial stages of my research were engaged in following Lasanthi (my landlady and research participant) around.

As illustrated in article 3 (18.05.2025), Lasanthi’s life was not an easy one. She received limited support from her family and suffered due to numerous emotional, physical and mental health issues. These issues made her regularly vent her frustration on her husband, her 80-year-old mother, and other family members and neighbours. Lasanthi and husband Chandana’s lives embodied the precarity and turmoil that existed within many homes in the relocated community.

While I witnessed regular internal strife on a micro level, constant interaction with Lasanthi and other community members in everyday life revealed the multiple systems with which Lasanthi and the community interacted. These systems included micro (family, friends), mezzo (interactions between families, communities, schools, religious places) and macro level (cultural, economic, political and social systems).

I regularly accompanied my participants to religious places especially St Anthony’s Church, Kochchikade, more recently associated with the Easter attacks and the untold grief that prevails in people’s hearts.

This vignette reveals a different experience of Kochchikade.

Passing the army checkpoint and security guards, we entered the church. After we crossed the main threshold, ‘Lasanthi Anti’ came alive. Rushing from shrine to shrine, she was a woman on a mission. First, the main shrine table. On her knees she went the length of the shrine for several metres, emerging triumphantly on the other side. Returning to the front of the shrine, Lasanthi tried to remove a mal maala (flower garland) from the shrine. Lasanthi was not blessed with height, so she struggled to clutch the mal maalava. A devotee graciously helped her. I was surprised!

Then Lasanthi dashed to the next shrine room. Reverently touching the shrine, she deftly removed a garland from the shrine in the same breath. I was shocked! Rushing to another shrine she returned with several garlands.

This time, she called me to remove the garland. I went forward. The shrine was elevated. Glancing upwards, I suddenly saw the Saint’s eyes gazing down at me. My fingers froze. The garland had been tied several times. Untying the garland, I gave it to Lasanthi. The couple in front saw me with the garland, their garland!! They were furious, “Why did you remove ‘our garland’? We just tied it there!”. I was speechless!

Lasanthi sprang into action, shaking ‘their garland’ in their face. “When you tie a mal maale on the shrine, it becomes sacred, after that you can remove it”. She then delivered an explanation regarding bhaara veema, and sacred and profane aspects of religion that even the renowned sociologist Emile Durkheim might have applauded. Unconvinced, the couple moved away, glaring at us. We decided the time had come to leave.

As we walked out, I glanced up, this time directly into the all-seeing red eye of the CCTV camera. My face burned with shame. I imagined the headlines, “Notorious mal maala horu, caught (Garland Thieves)!”

My fieldwork with urban residents living in the URP was characterised by much drama, hilarity and ethical dilemmas. The urban poor are often demonised as “duppath, nuugath, kudda” and their homes are stereotyped as ‘slums and shanties’, and more recently as ‘virtual slums’. Their professions as port workers, naatamis, fish market vendors, garment factory workers, or cleaners are often described in pejorative terms, and the only accolades that are awarded to these communities are labels of vulnerability and criminality.

However, there are multiple lessons that could be learnt regarding community building from these communities. Despite the sense of despair regarding community disarticulation in high-rises and regular complaints regarding increasing isolation in the flats, the attempts to construct community cannot be ignored. Lasanthi’s mal maala collecting underscores what might be perceived as morally ambiguous faith. However, her acts of religious worship, albeit performative, were poignant. At times the moments she spent in front of Mage Yesu (my Jesus), Amma’s shrine (Mother Mary) and Saint Anthony’s shrine were intensely personal, where her turbulent mind was at peace. She left home early in the morning, she did not eat or drink till noon, and her visits to church nourished her.

Such religious rituals were not only important for Lasanthi, a Sinhala Catholic, but integral to the whole community. In my household sample of 320 households, only one householder claimed he was an atheist. Religion performed a vital personal function for most residents who between 5-8 a.m. and in the evening between 5-7 p.m. would engage in religious rituals. Although to different religious figures, these were significant as the entire community coalesced in an individual but united direction.

One might assume Lasanthi took the mal maala to make a fast buck, but this was not so. Returning to the flat, Lasanthi went from home to home distributing mal maala to the community members. This simple act was significant on a community level. For watta dwellers relocated to a grey, concrete flat with limited greenery, Lasanthi’s mal maala provided them with a pleasant sensorial experience and evoked nostalgia of their watta. Moreover, many felt that “real flowers” enhanced their chances with divine authorities than the miserable plastic flowers they offered.

It was only after Lasanthi shared the mal maala with her neighbours that she placed one on her home shrine. This was not merely homemaking but a transformative act of community-based sharing.

The series showcased the invisible often neglected people in Colombo like Lasanthi, their resilience, their community-based practices and unique strengths that can create a stronger sense of belonging and solidarity in Colombo. We are often hampered by political divisions, development disruptions, the impact of socioeconomic and political plans and policies on a macro level. However, ordinary people and everyday community interactions that occur on a micro and mezzo level must be utilised to create the transformation required in Colombo and the country.

(Avanka Fernando is a researcher and lecturer at the Department of Sociology, University of Colombo. Her interests include exploring cities, communities, urban poverty and listening to people’s stories)

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.