FTAs: Substitute for free trade?

View(s):In Sri Lanka’s case, I believe neither path was pursued effectively. The journey toward free trade, after gaining some momentum, eventually faltered and began to reverse midway. Similarly, the efforts toward establishing FTAs also fell short. Despite initial steps—signing two bilateral FTAs with India (2000) and Pakistan (2005)—no consistent strategy followed to expand or capitalise on these agreements.

“Desire and fear”

The concept of FTAs being the ‘second-best option’ suggests that, instead of implementing comprehensive policy reforms aimed at achieving free trade, countries may opt for FTAs as an alternative. This approach implies that while maintaining protectionist policies—such as import controls—we selectively open the door to free trade with one or a few partner countries.

This perspective is driven by the notion that, although free trade yields superior outcomes, the transition costs associated with policy reforms can deter its adoption. As a result, FTAs are seen as a compromise—a way to partially benefit from free trade without fully abandoning the existing status quo.

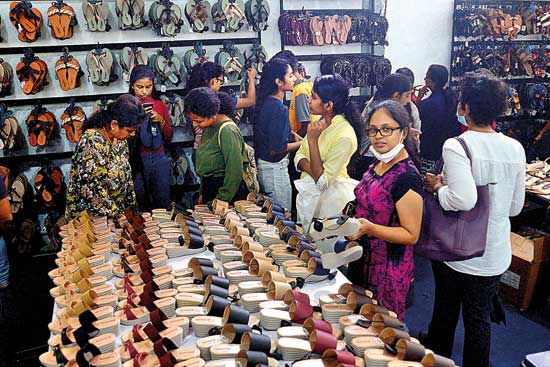

Local producers complain about cheaper imported shoes.

Another interpretation of the ‘second-best option’ views FTAs as preliminary steps toward achieving free trade. For countries hesitant to embrace free trade with the global community via unilateral policy reforms, FTAs serve as a gradual opening to select partner countries. Over time, this incremental process can lead to broader agreements with multiple nations, eventually paving the way for attaining full free trade status.

Common tariff principle

Let us examine the extent to which these notions can be supported by economic analyses. Consider the example of a country that imports a certain commodity produced by multiple nations and subsequently signs a bilateral FTA with one of them. The commodity in question could be a consumer good, such as a food item; an intermediate good, like building materials – cement or steel; or a capital good, such as machinery or equipment.

Previously, all imports of this commodity, regardless of their country of origin, were subjected to a common tariff rate at the point of entry. This practice aligns with the Most Favoured Nation (MFN) principle established by the WTO to promote fair trade. Ironically, the MFN principle implies the ‘opposite’ to what its name might suggest—it prohibits member countries from imposing discriminatory tariffs on different trading partners (although the recently announced US reciprocal tariffs violate this principle).

As a result, imports of the commodity from various countries faced the same level of tariffs in line with MFN principle, fostering an environment of non-discriminatory competition. This setup incentivised suppliers to compete for market share by offering better quality and more competitive pricing.

Trade diversion

After entering into a bilateral FTA with one of these countries, the commodity that comes from that country enters free of border tariffs and other import controls. This is accepted by the WTO, deviating from the MFN principle. In effect, the commodity becomes cheaper in the local market than the commodities supplied by all other countries.

The outcome is clear: The commodities that come from all other countries would be more expensive than the commodity imported from the country with an FTA. Accordingly, all the countries which have no FTA will lose market competition enabling the country with FTA to build its monopoly powers in the local market through trade diversion.

The outcome is clear: The commodities that come from all other countries would be more expensive than the commodity imported from the country with an FTA. Accordingly, all the countries which have no FTA will lose market competition enabling the country with FTA to build its monopoly powers in the local market through trade diversion.

If the commodity was in inferior quality, now it can even survive and thrive in the local market where other commodities with superior quality would disappear. And the FTA has finally resulted in a distorted trade pattern, which did not exist before even with import controls.

Manhole of a fortress

The above example offers valuable lessons, illustrating that FTAs are not necessarily the ‘second-best option’ for achieving prosperity. In fact, they might even steer a country in the opposite direction if implemented under unfavourable conditions.

FTAs, therefore, are not unconditional agreements. Certain preconditions must be met to minimise the risk of trade distortions arising from these arrangements. The most critical factor is the overall trade regime of the country where the FTA is introduced.

If the country has erected a highly protective barrier against imports and creates a selective opening—like a ‘manhole’—for free access to just one partner country under an FTA, this could represent one of the ‘worst’ forms of trade agreements. This is because, under such circumstances, trade distortions become likely. Granting preferential access to one trading partner through an FTA may lead to an unfair advantage, both against other trading partners and against the domestic economy itself.

For this reason, FTAs are not an appropriate policy choice within a complex and heavily protective trade regime. Instead, FTAs should be implemented within the framework of a fairly liberalised trade regime, supported by a consistent and ongoing reform process.

Least beneficial FTA

Among trade agreements, ‘bilateral FTAs’ are often considered the ‘least beneficial’ option. Such agreements open the markets of two countries to each other for free trade. However, compared to regional or multilateral FTAs, the benefits of bilateral FTAs are constrained by the inherent problems of limited market of the two participating nations.

The likelihood of trade distortions is higher in bilateral FTAs than in regional or multilateral agreements. In a regional or multilateral FTA, which involves multiple countries forming a larger free trade area, there is a greater chance for competitive producers to operate within the bloc, leading to more robust competition than in the limited scope of a bilateral FTA.

This dynamic ensures that member countries in a regional or multilateral FTA are less likely to foster environments that lead to reduced competition or monopolistic practices. A prime example is the European Union, which began in 1957 with six member nations (Germany, Italy, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg). Over time, it expanded its membership to include 28 countries, incorporating even many transitional economies in Eastern Europe and creating a vast, competitive free trade area.

Larger trading blocs

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) began as a regional bloc in 1967, initially comprising five member countries—Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand. Over time, ASEAN expanded into a 10-member regional bloc, eventually evolving into the largest free trade area in the world under the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). This agreement includes 15 member nations from the Asia-Pacific region, further solidifying its global economic influence.

FTAs alone cannot overcome a member country’s domestic challenges. While FTAs can potentially provide access to larger markets and opportunities for enhanced trade and investment, these benefits are not guaranteed. A member country may fail to realise substantial gains if domestic constraints hinder business operations and economic growth.

To fully capitalise on an FTA, a member country must first implement significant policy reforms and cultivate a favourable business environment. This reinforces the argument that unilateral reforms are a crucial prerequisite for maximising the advantages of FTAs.

Trade creation

When a country opens its market to free trade through an FTA, certain ‘inefficient’ domestic production activities producing competitive goods are likely to wither away. This often occurs because partner countries may have more favourable conditions for production, allowing them to offer higher-quality goods at lower prices.

Many critics view this as a justification for opposing FTAs. While this concern holds merit at an individual product level, a broader macroeconomic perspective frames it as part of trade creation and specialisation—an inevitable process that affects all member countries within an agreement.

As a result, its opposite would happen too. An FTA-member country may experience both the expansion of some industries and the contraction of others. However, the overall impact of trade creation at the national level tends to be positive rather than negative.

To mitigate potential adverse effects, countries may exclude certain goods from FTA provisions by maintaining a ‘sensitive list.’ However, if a country’s sensitive list is excessively large, the benefits of negotiating an FTA become negligible.

Spaghetti bowl

The key takeaway from FTAs worldwide is that they are not a replacement for free trade. Instead, policy reforms aimed at achieving free trade serve as essential pre-requisites and complements to FTAs, ensuring their outcomes are more effective under liberalised trade conditions.

Why shouldn’t a country pursue as many FTAs as possible? Too many FTAs with numerous trade partners can lead to a highly complex trade regime, often referred to as a “spaghetti bowl”. Managing an excessive number of overlapping FTAs like in a spaghetti bowl creates administrative challenges and inefficiencies. The increasing complexity and costs of managing multiple FTAs reinforce the argument that unilateral trade reforms remain the most effective path toward achieving free trade.

(The writer is Emeritus Professor at the University of Colombo and Executive Director of the Centre for Poverty Analysis (CEPA) and can be reached at sirimal@econ.cmb.ac.lk and follow on Twitter @SirimalAshoka).

Hitad.lk has you covered with quality used or brand new cars for sale that are budget friendly yet reliable! Now is the time to sell your old ride for something more attractive to today's modern automotive market demands. Browse through our selection of affordable options now on Hitad.lk before deciding on what will work best for you!