Arts

Regaining our lost treasures

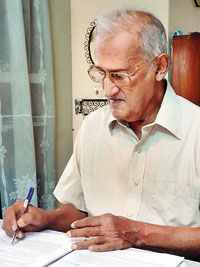

View(s):As Sri Lanka marks 76 years of Independence, Kumudini Hettiarachchi looks at the meticulous work done by an unsung hero Dr. P.H.D.H. de Silva, Director of National Museums in the 1970s in tracing thousands of artifacts scattered around the globe.

The late Dr. P.H.D.H. de Silva

Six invaluable cultural objects including the intricately-carved and bejewelled Levuke cannon have come home amidst much fanfare, but as Sri Lanka commemorates its 76th Independence Day, concerns rise about thousands of others scattered across the world.

The Netherlands, in December 2023, returned the cannon, two ceremonial swords (a golden and silver kasthãné or sabres), a golden knife and two guns (maha thuwakku or wall guns) looted more than 250 years ago from the Kandyan Kingdom by the Dutch East India Company in 1765. The Dutch government approved the return of these historic objects, displayed at the Rijksmuseum, in Amsterdam, in 2021.

What of the other cultural objects, question many including Prof. Naazima Kamardeen, Chair Professor, Department of Commercial Law, Faculty of Law, University of Colombo, who has been passionately researching the legal background of Sri Lanka’s long-lost treasures.

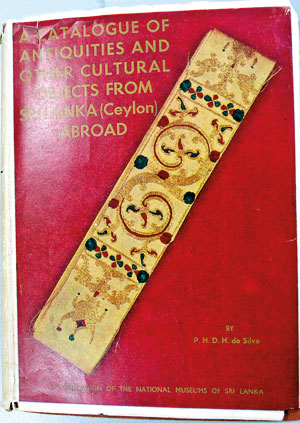

And it is not as if Sri Lanka is groping in the dark……a precious book with yellowed and crumbling leaves shows them all – “our” cherished objects in other countries.

Meticulously documented in ‘A Catalogue of Antiquities and Other Cultural Objects from Sri Lanka (Ceylon) Abroad’ in 1970 by unsung hero Dr. P.H.D.H. de Silva who was the then Director of National Museums, are thousands, nay more than 15,000 to be exact, of artifacts in 23 countries.

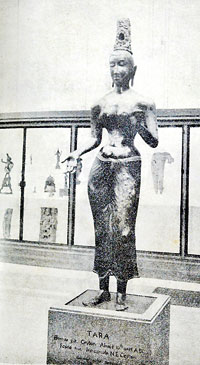

The statue of goddess Tarä (8th-9th century), the only work of its kind, now in the British Museum, London

Clearly listed in alphabetical order are the countries ranging from Australia to the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States of America (USA), with even unlikely names such as Brazil, Hungary, India, Mauritius Islands, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe and Zambia) and South Africa.

The Catalogue states that these objects are in 140 foreign museums and libraries including the UK’s British Museum and Victoria & Albert Museum; the Netherlands Rijksmuseum & Tropenmuseum and Switzerland’s Museum Fur Volkerkunde, Basel. The collections have been classified as – ‘Prehistory’, ‘Numismatics’, Art & Antiquities’, ‘Palm-Leaf Manuscripts’ and ‘Anthropology’.

Interspersed among descriptions of these objects are black-and-white photographs with only the cover and a few others in colour.

Prof. Kamardeen (who had met Dr. de Silva just once before his demise) and I turn the pages of the catalogue gingerly, marvelling at the dedication of the compiler and the effort that has gone into this work.

We pick on the three last colonial powers which held Sri Lanka in their grip – there are no entries for Portugal, but there are many for the Netherlands and the thickest or 1/3rd of the book (from Pages 125-350) is devoted to Great Britain.

The range of looted objects is wide and varied – ola-leaf (palm-leaf) manuscripts to jewellery to swords to everyday-used items such as elaborately-carved combs, ivory pestles and mortars to baskets (cane to reed), masks and clay items and going up in value to royal items.

The return of artifacts to former colonies is a contentious and sensitive issue. A classic example is the longstanding dispute between Britain and Greece over the beautifully sculpted ‘Elgin marbles’, now called the Parthenon Sculptures, a collection of ancient Greek sculptures and architectural details in the British Museum, London.

Referring in general to looted bounty from Sri Lanka, Prof. Kamardeen says the haggling begins when the former colonial powers question the “nationality” of the objects in their possession.

Prof. Naazima Kamardeen

She cites a National Museum official who spoke of the intricate design of a Maha Thuwakkuwa which included a screw mechanism created in Ceylon in the 17th century. This particular mechanism had been patented in the USA only in the 19th century, she says, looking at other “hidden” missed opportunities for the country because this weapon was not with us.

“Such minute details are also a pointer to how developed we were,” she says, going into another forgotten angle, works of art which may have been painted by a foreigner during the colonial period, with the scene being from then Ceylon. We still do not have evidence to say we had “prior art”.

She refers to the step-motherly treatment accorded to Asia and Africa by Europeans, as opposed to their neighbours, whether far or near.

“When it came to other European countries, they did not take much as spoils of war, which rule did not apply to their colonies in Africa and Asia. They felt that we were uncivilized and whatever objects they wished for, be they cultural or religious, they could appropriate at will,” she says.

Prof. Kamardeen also looks at the concept of de-humanization where the colonial powers felt that when they took away such objects, even if they did not wish to possess them, they deprived us. This was the policy adopted in European colonial expansion.

She pays tribute to the late Dr. de Silva who not only compiled the comprehensive catalogue but also wrote up claims and restitution requests to get them back home.

Another argument put forward by Prof. Kamardeen is that while such requests are being reviewed, the foreign museums which are exhibiting such objects and charging fees for entry should consider paying some form of compensation to the countries from which these objects were originally taken.

The cover photograph on the catalogue is described as the ‘Frontispiece – Palm leaf cover of Talpata from the Chiefs of Kandy to the Dutch Governor in Colombo, Iman Willem Falck. Item No 935 at the Bibliotheque Nationale – Paris’.

“We have not given them as gifts. Therefore, they can think of them as a long-term loans, from which they earn by exhibiting them, and pay us a fee,” she points out.

Looking at the recent past, she says that the first global legal instrument to address the issue of the illicit movement of cultural property was the 1970 ‘Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property’.

However, she reiterates that it operates only after 1970 and provides for any discussion on objects moved illegally prior to its operation only at bi-lateral level. For this purpose, UNESCO instituted the ‘Intergovernmental Committee for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property’ (ICPRCP) to its Countries of Origin or its Restitution in case of Illicit Appropriation, which was formed in 1978.

Hot on the heels of the setting up of ICPRCP, Sri Lanka’s Dr. de Silva had drafted a request in 1979 for the return of cultural property lost during the colonial period. However, since the ICPRCP required that both parties fill out the form, and this was not done, the request had not accommodated.

This is what Dr. de Silva had stated: “………Some nations may be able to boast of a preponderance of high-quality movable cultural objects from their countries, but so far as Sri Lanka is concerned this is not true. It is my experience that outstanding movable cultural objects from Sri Lanka are comparatively few and their removal from my country creates a cultural void which cannot be filled.

“For example, the 143.5 cm high gilt bronze of Tarä (eighth to ninth century AD) presented in 1830 by Sir Robert Brownrigg, the British Governor in Ceylon to the British Museum in London, is the only one of its kind so far found in Sri Lanka.

“Also unique are the two exquisitely carved, gem-studded ivory caskets dispatched by the Sinhala Monarch, King Bhuvanoka Bahu VII of Kotte to King Don Juan III Portugal in or about A.D. 1542, which are now in the Schatzkammer der Residenz, in Munich (Germany). The royal letters on palm leaf from the Palace of Kandy to the Dutch Governors in Colombo are in Paris (France) and Amsterdam and Leiden (Netherlands). The only impression to my knowledge of the seal of the Palace of Kandy (Maha-wäsala) is at the Tropen Museum, Amsterdam. Our best masks are in the United Kingdom, Federal Republic of Germany, Czechoslovakia, Sweden and Norway. This list could go on.

“Another feature, which I have personally experienced to my dismay, is the rich collections from the ‘deprived‘ countries, including my own, in storage in several important museums in Europe and the United States, some of which are rarely exhibited to the public. Indeed, some of these same institutions are crying out for more and more objects from our countries.

“I believe I am voicing the opinion of several others in the ‘deprived’ Third World countries that we are not requesting the return of every single object, document, etc., taken away. We think that the cultural image of our countries abroad is as important as it is in our own countries. We are asking for the restitution of only those unique and specially-significant items which express to the world and to our own countrymen the unique cultural heritage that is ours and our craftsmanship par excellence.”

Crowds admiring the Levuke cannon on its return. Pic by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

Dr. de Silva goes onto say that Sri Lanka was fortunate in obtaining as an outright gift some outstanding art treasures of the Kandyan Monarchy. On September 23, 1934, the Duke of Gloucester on behalf of the King of the United Kingdom, had presented the throne and footstool of the last kings of Kandy and the crown of King Sri Vikrama Rãjasimha and on September 10, 1936, the sceptre, the ceremonial sword and the cross belt of the last King of Kandy had been presented by command of King Edward VIII.

Sadly, though, after many decades of Dr. de Silva’s efforts, the call for the return of Sri Lanka’s objects has fallen on deaf ears.

A unique carved, gem-studded ivory casket now in Munich’s Schatzkammer der Residenz, Germany

The throne and stool of the last King of Kandy (19th century) returned to Sri Lanka at the command of King George V of the United Kingdom