News

Glyphosate & hard water: Is it a deadly CKDu combination for farmers?

View(s):- US-SL scientists find ‘extended’ life to these complexes in drinking water wells and raise concerns on the impact on human health

By Kumudini Hettiarachchi

The cause of the kidney disease felling the farmers of the Dry Zone has been established as being ‘multi-factorial’ over the years.

Another piece of the puzzle linked to Chronic Kidney Disease of unknown aetiology (CKDu) has now been found by a Sri Lanka-US research team collaborating across the seas to shed more light on it.

The “combination” of glyphosate – found in a commonly-used herbicide – with elements in hard water, gives glyphosate an extended life. Those complexes can persist up to seven years in water and 22 years in soil, the study found, raising critical issues about the impact on people’s health.

‘Roundup’ is a glyphosate-based herbicide used to control weeds and other pests and as it is supposed to break down in the environment within a few days to weeks, its use is relatively under-regulated by most public health agencies, it is understood.

“It was always thought that this chemical would break down very quickly in the environment, but it seems to stick around a lot longer than we expected when it complexes in hard water,” said Prof. Nishad Jayasundara, the Juli Plant Grainger Assistant Professor of Global Environmental Health at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, United States of America.

Samples from a farming community

He underscores that what needs to be considered is how glyphosate is interacting with these other elements (trace metal ions such as magnesium and calcium which make water hard) and what happens to glyphosate when taken into the body as a complex.

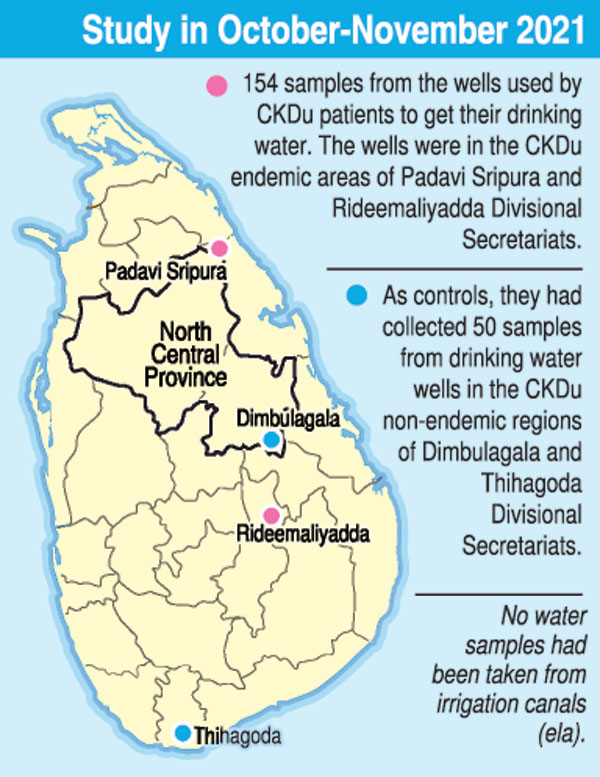

Prof. Jayasundara and his team had conducted this study in October-November 2021, collecting 154 samples from the wells used by CKDu patients to get their drinking water. The wells were in the CKDu endemic areas of Padavi Sripura and Rideemaliyadda Divisional Secretariats.

As controls, they had collected 50 samples from drinking water wells in the CKDu non-endemic regions of Dimbulagala and Thihagoda Divisional Secretariats. No water samples had been taken from irrigation canals (ela).

The Duke University team (which also included environmental chemist and Associate Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Lee Ferguson and PhD student Jake Ulrich) had collaborated with colleagues from the University of Ruhuna led by Prof. P. Mangala C.S. De Silva of the Department of Zoology.

It had been Prof. Ferguson’s lab which employs high-resolution and tandem mass spectrometry to identify contaminants — even the barest trace of them — by their molecular weights, that had allowed a broad view into the pollutants present in the well water in CKDu-affected areas.

Through this highly-sensitive technique, the researchers had found significantly higher levels of glyphosate in 44% of wells within the affected areas versus just 8% of those outside it.

Prof. Nishad Jayasundara (on the left) and Prof. P. Mangala C.S. De Silva during their field studies

The results of the study have been published in ‘Environmental Science and Technology Letters’, a respected, peer-reviewed scientific journal of the American Chemical Society (ACS) in September.

“We really focused on drinking water here, but it’s possible there are other important routes of exposure—direct contact from agricultural workers spraying the pesticide or perhaps food or dust,” Prof. Ferguson has said, adding that he would like to see increased study with more emphasis

looking at the links among these exposure routes. “It still seems like there might be things

we’re missing.”

Delving into the disease, Prof. Jayasundara says that CKDu is a clear example of a human disease resulting from environmental change. Studying it is relevant to Sri Lanka as well as a multitude of CKDu-impacted communities around the world. It is also critical to highlighting how important it is to ensure a sustainable future that promotes living in harmony with the natural environment.

“CKDu has resulted in a significant socio-economic burden, threatening basic ways of life for many communities around the world, who are often voiceless on the global stage. It is important to remember that farming communities are the base of human survival and it is our collective responsibility to ensure their wellbeing. So, we wanted to highlight the risk factors to the health of these communities and contribute, even in a small way, to improving outcomes for the impacted people,” he says.

Collecting water samples from drinking wells

Looking into the recent past, this scientist says the first evidence of CKDu was identified among paddy farmers in the North Central Province (NCP). This is while recent studies among farming communities in the outskirts of the NCP in areas such as Buttala and Moneragala have also reported CKDu, but a lower incidence rate than the NCP. Studies across the Dry Zone, meanwhile, have also shown that

communities in Moneragala and Hambantota districts are also impacted.

“We do think CKDu is a result of multiple environmental risk factors coming together. To get to the bottom of this, we now have longitudinal studies ongoing, to evaluate long-term exposure to these compounds. In parallel we are doing animal exposure studies to understand how glyphosate in combination with metal ions may affect kidney development and kidney health. This will help us develop better markers of exposure as well as diagnostic measures of early signs of poor kidney health to inform at-risk communities,” he adds.

| Children in danger too in CKDu areas The kidney health of children in CKDu communities is impacted and our estimates predict that 3-10% of children in these communities live with some level of kidney injury, warns Prof. Nishad Jayasundara, referring to their work, especially by graduate student Sameera Gunasekara. Explaining that studies coming out of Mesoamerica suggest the same burden on children’s kidney health, he says that the later life consequences of this in children are not known and more longitudinal data would be needed to get a better picture. “However, our data on children clearly indicate environmental risks to kidney health that calls for immediate and efficient action,” he stresses. Multiple studies in different communities indicate CKDu cases ranging between 5-20% in regions with a high burden of CKDu such as the North Central Province. However, the burden in the outskirts of these regions remains uncertain, according to him.

| |

| Need for urgent steps – clean drinking water; screening for CKDu & repair of RO units in schools It is important to recognize the risk factors that can be eliminated to improve the well-being of farmers and their families – is the strong plea by Prof. Nishad Jayasundara. He stresses that the “very” urgent need is provision of clean drinking water, especially so that children in these communities can minimize their risk of CKDu. This is because drinking water is posing a significant risk to kidney health with the persistent presence of pesticides such as glyphosate, as well as other chemical elements like vanadium and compounds like fluoride. Water hardness seems to contribute to stabilization of glyphosate in the well water and that is another solvable issue, he says. Prof. P. Mangala C.S. De Silva reiterates that in their studies they have found that when clean drinking water is provided, the CKDu prevalence rate reduces. However, this should not lead to a curbing or reduction in CKDu screening programmes in these areas. Scrupulous maintenance and repair of Reverse Osmosis (RO) Units (water purification units) in schools in these areas, is another very important factor highlighted by him. “Someone needs to be responsible for maintenance and repair and it is imperative for the government to take a policy decision on this,” he adds. |

The best way to say that you found the home of your dreams is by finding it on Hitad.lk. We have listings for apartments for sale or rent in Sri Lanka, no matter what locale you're looking for! Whether you live in Colombo, Galle, Kandy, Matara, Jaffna and more - we've got them all!