Sunday Times 2

75 years after: A Sri Lankan Midnight Child’s story

View(s):By Sarath Amunugama

It is now 75 years since that famous day and many people and things near and dear to me, including my parents, friends and social activists, are no more. So there is a certain sadness in me when looking back. But at the same time I also have a feeling of a tragic loss of the promises held out to us for a new beginning when compared with the tragedy of our present times. However to be realistic there have been both gains as well as losses during this period and now 75 years later is the time to look at them afresh. There is no doubt that this period has seen many advances particularly for the disadvantaged and oppressed rural community. Economists like Amartya Sen have advocated this model of inclusive growth even though there are reservations about how it all panned out.

Let us go deeper into these changes.

The first obvious difference is what is called the ‘demographic transition’.At the time of independence we were about 71 lakhs of people. Today we are over 210 lakhs and soon will be reaching 230 lakhs before we hit a plateau in population growth according to demographers and statisticians. Before social interventions became the rule in the modern world, according to the now abandoned Malthusian theory, there was a balance in population growth because the natural increase in births were matched by the death rates. High maternal and infant mortality was a characteristic of the pre-modern period and it accounted for the slow growth of populations.

Some modern historians have demonstrated that the spurt of activities in western Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries –particularly their advances in seafaring and conquest of new territories – leading to colonialism, was a function of rapid demographic changes in those countries. With the elimination of “Black Death’’or plagues and the development of inventions following the Renaissance they were able to master long range navigation in their search for the ‘Americas’. By accident they came to the East and inaugurated the “Vasco De Gama’’of modern Asian history as propounded by K.N. Pannikar, the famous Indian historian. (In passing we may also note that seafaring and regional trade was also a characteristic of medieval Asia).

In Sri Lanka the stage for rapid population growth was set in the later colonial period. However the granting of universal franchise in 1933 following the recommendation of the Donoughmore Commission led to a spate of social welfare measures promoted by the newly elected State Councillors. Among these changes, rural health was given priority. Accordingly rural hospitals and village level health care led to the drop in maternal deaths and a rapid increase in births largely due to the drop in infant mortality. There is an argument among demographers about the reasons for this leap in rural health. The Editors of ‘Population’ ascribed it to the discovery of DDT and the conquest of Malaria. Ananda Meegama and others have argued persuasively that it was due to a raft of social welfare undertaken at that time including food subsidies, educational reform and the transformation of the rural health sector.

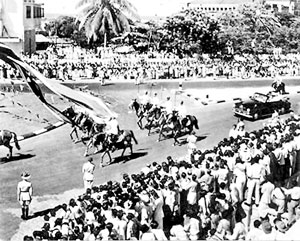

When hopes were high: The Independence ceremonies in 1948

With independence the emphasis on social welfare was intensified. Not only did we have a surplus of sterling reserves but the later Korean War sent rubber prices sky high and the early Senanayake regimes were able to complete major development activities like the Gal Oya scheme and the construction of an idyllic new residential University in Peradeniya with domestic savings. But that could not last long because of several reasons including population growth mentioned above. No attention was paid to the need to transform our economy freeing it from dependence on exports of tea, rubber and coconut and a domestic small farmer-based agriculture which was so inefficient that we had to regularly import our staple food – rice from Burma and even locate an embassy there to ensure that there was no break down in food supplies.

But this honeymoon could not go on. After his unanticipated victory in 1956, SWRD Bandaranaike raised alarm bells and advocated population control while as Prime Minister Mrs. Bandaranaike said the following in 1972: “The continued growth of population at the present high rate will pose problems which will defy every attempt at solution. In the short term any further increase of the number of births from the present level of 370,000 per year will put inordinate strains on the school system, on hospitals and the supply of other goods and services and in such a situation, it is only by a shift of investment in productive activities that it would be possible to maintain these services even at present levels.’’

How to face this impending crisis? It was here that political ideologies came into play and ensured that we proceeded on the path that has led to the present crisis. It is noteworthy that all recently emancipated nations in South Asia first undertook to sponsor growth through Statist policies. Given the linkages between a feeble native capitalism and the departing colonial administration, leaders of these new nations emphasized a state-led growth at the expense of a possible open economy. The argument was that only the newly emancipated State had the resources to stimulate growth. When the Bhakra Nangal dam was opened, Nehru called it “The Temple of modern India’’.

In Sri Lanka free education, free health, subsidised transport and social welfare handouts were paid out of the earnings which were becoming more and more difficult to obtain. The history of our external sector is one of assisted suicide. All the traditional income earners were systematically decimated by bringing them under state control which was at the heart of mismanagement and corruption that followed. The so called Socialist state with its “licence raj’’ was the epicentre of corruption, inefficiency, patronage and loss of markets. One may think that the above observations were only in respect of Sri Lanka. Not so. They became well known as the drawbacks of the Nehru (Jawaharlal and Indira) led economies which were referred to sarcastically by economists as “The Hindu rate of Growth”.

It was only after the Indian economy was opened up following the fall of the USSR and Eastern European economies and the growth of China after the fall of the ‘Gang of Four’ which advocated Mao’s disastrous economic theories, that India under the leadership of Manmohan Singh and Chidambaram took to the path of economic liberalization which has led to spectacular results. While admittedly there are imperfections in the liberal economic system, today’s growth of the technology-led competitive economic system so created has led to greater productivity and the common good. Such spurts of economic growth in our country were seen only when a policy of foreign investment, higher technology and an open competitive economy was allowed to operate even for a short while. It enabled us to capitalize on our greatest asset which is our hub position in the Indian Ocean.

Amartya Sen in his recently published autobiography ‘Home in the World’ revisits theoretical debates on this issue among the world’s leading economists some of them Keynsians like Kaldor, Joan Robinson and Richard Kahn and others – ‘Neo-classicalists’ like Denis Robertson. There were also Marxists like Dobbs and Piero Sraff at Cambridge University. Being a student of Marxist theoretician Sraffa Gramschis’ friend and benefactor, Sen hews a line which has now been rejected by Indian planners when he says regarding Joan Robinson’s views, “Somehow Joan had little sympathy for the Smithian integrated understanding of economic development. For example she strongly criticized Sri Lanka for offering subsidized food to everyone on nutritional grounds and for the sake of good health, even though it contributed to economic expansion at the same time. She dismissed such a mixed strategy with a highly misleading analogy ‘’Sri Lanka is trying to taste the fruit of the tree without growing it.”

Seventy five years after independence we have not yet discovered the growth model that will suit the particularities of our situation. Like the proverbial blind man we touch different parts of an elephant’s anatomy and recommend models which do not appear to work in terms of economic growth. Ironically it has been the Left which has chosen to emphasise a ‘National Economy’’citing odd instances like importing apples and grapes. What they have done through populist politics is to make all the mistakes which ruin a functioning economy. In the ‘nationalising spree’’of the SLFP and its toadies in the Left, plantations, trade, transport, shipping, the Port, Airlines, fuel distribution and insurance and many other ventures which were running efficiently with good management were all taken over and decimated. Profit generating ventures which were well managed were turned into employment exchanges for relatives and hurrah boys. Systematically the country was deliberately – because of an outdated ideology which later brought down the Communist system in the USSR and Eastern Europe – set on the path to economic ruin.

It is a strange irony that the very masses who were mesmerised by the populists are now protesting against the loss of benefits which can only be sustained by a growth momentum which they rejected at the polling stations.

When I met Amartya Sen several years ago in Delhi, I asked him why his recommended development growth model of Sri Lanka had failed. His answer was that the ethnic conflict had blunted that growth trajectory. There may be some truth to that assertion but what he fails to recognize is that the very ethnic conflict was created by the misuse of Statism which underpinned that growth model. Countries like Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos and Rwanda have, after the end of internecine wars, fuelled rapid growth through a market economy model which has linked itself to a globalized economy. Only Sri Lanka has not emerged richer unlike the above mentioned countries.

The reason for this must surely be wrong leadership which follows a populist anti-growth programme and relies on policies which benefit a narrow ruling political class which like in Marcos’ Philippines established a kleptocracy and family rule which while throwing crumbs at their followers, indebted the country and focused their attention on the wrong “enemy” by rousing communal passions. We, at this juncture, need a strong intellectual debate on how to fashion our future economic policies based on productivity, sound management, elimination of corruption and selfless leadership. That was the message that the youth of this country attempted to send through the Aragalaya.

Trotsky wrote of a “Permanent Revolution’’. An Aragalaya is never over until wrong policies and wrong leadership using populism to divert attention from the realities of economic growth to gain power continues to dominate our society.

(The writer is a former member of the Ceylon Civil Service and one-time Cabinet Minister. He graduated from the University of Peradeniya and taught Anthropology at both the Universities of Peradeniya and Vidyodaya. Later, he obtained a Doctorate from the Centre for Advanced Social Studies in Paris, France and was a senior official of UNESCO)