He leaves behind a gigantic trail and stories only he could have told

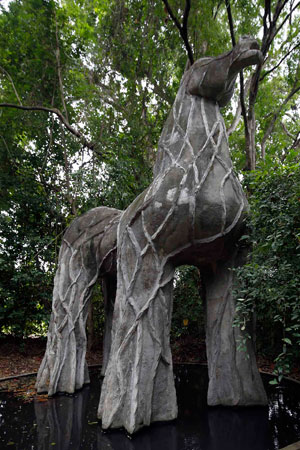

It is being said that an eerie silence pervades Diyabubula. The three-toed kingfisher has magically reappeared and the water monitors have all come ashore. The fish owls are hoot-less; the monkeys declared a swing-less day while the hump-nosed viper found common ground with the Indian krait and the Trojan horse stands head bowed. They are missing the colossus of a man who watched over them twirling his beard, whistling in perfect tune to return their screeches and calls. They are also missing his music that crashed through the trees from giant speakers amongst the lush undergrowth belting out Floyd, Bach, Cohen and Brubeck.

Typical Laki: A twinkle in his eye and twirl of the beard. Pic by Indika Handuwala

Laki left behind a gigantic trail of art, architecture, gardens, sculptures, chandeliers, owls, friends, prose, ponds, and flutes. Kindness, compassion, unconditional acceptance, Diyabubula and stories that only he could have told. But he had not one foe to leave behind.

An artist, agriculturist, draftsman, botanist. A mathematician, engineer and humanist. He named his only daughter after the third star in Orion’s belt and defined his classical music tastes as Bach and backwards and Stravinsky and forwards. He was a single father. His mother was a LSSPer and the first woman MP of Parliament. I heard Laki once say that, “revolution was the opium of the intellectual”.

Diyabubula or “bubbling water” had a simple pavilion as a house surrounded by boulders and ponds with a roof cooled by a thatch of coconut husks and over it a mat of the creeper Wel Kohila. Everybody who visited experienced Laki’s unique hospitality equally. It was a haven, a refuge, a retreat and sometimes even rehab for those using a crutch or a prop for their floundering emotions. In the early days I have seen messages scrawled upon the walls thanking Diyabubula for setting them free. Each of us have special stories about our superlative experiences at Diyabubula.

Laki found art as enforced in school tiresome and devoted his time to leaping about on a diving board at Royal College. When his art teacher Cora Abraham told him that he had no real style of his own and was “fractured”, she had also freed him because he said as long as he was a fractured artist, he could do anything that he wanted. It has thus been impossible to keep track of Laki’s work because he was such a prolific and diverse artist.

But much has been written about it and more will be written soon, I am sure. So, I will leave that to the experts. He worked closely with architects like Geoffrey Bawa, Valentine Gunasekera and Ulrik Plesner, Bevis Bawa the landscapist and designers like Ena de Silva and Barbara Sansoni. Few would be aware that in 1979 Laki was commissioned by the Central Bank to design a set of currency notes using his drawings of indigenous flora and fauna. The bank notes were awarded the first prize in the exposition of Numismatics Paris in 1985.

Towering sculpture: Laki’s Trojan horse at Diyabubula. Pic by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

Writing about Laki will not be complete without mention of Noel. His ADC, companion, collaborator, comrade, confidante and constable. He loved and cared for Laki absolutely and Laki was able to be Laki because of Noel and the spaces he created, protected and nurtured for him. Laki’s other band of Diyabubula pioneers were his daughter Mintaka, Some, Lizzy and (the late) Uncle. When he came over in 1971 to grow chillies armed with Nihal Fernando’s book on farming to start up a commune and go native, economics swiftly transformed those ideals into a bustling centre for his creativity that simply had no boundaries.

He designed my home and I quickly realized his eye for brutal corners, pillars, arches, grills, courtyards and pergolas. And when my father died leaving behind a crop of unsigned (and unseen) paintings, Laki walked in one day and asked what I was doing with these brilliant works of art. He empowered me to hold my father’s first and posthumous exhibition and I could do it because Laki walked beside me all along the way.

For those of us who have sat with Laki at dawn, noon and twilight on that magical deck under the shade of that tree, there is a silver thread that has bound us to him from which we would never wish to extricate ourselves from. To me, Laki was the epitome of humility, egoless, and an absolutely non-judgmental human being. A true nonconformist. He will surely rest in peace.

Jomo Uduman