Columns

- Foreign Minister calls the Resolution “illegal” after its adoption

- A new Secretariat in Geneva to probe “future” violations of human rights

- India abstains disproving Foreign Secretary Colombage’s claims

- Lack of professionalism in diplomacy a main cause

The worst ever resolution on Sri Lanka by a world body, since the country’s independence 73 years ago, passed muster at the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva on Tuesday.

That the document (L.1 /Rev.1) titled “Promoting reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka,” would pass was foregone though a Minister and a bureaucrat made Sri Lankans believe otherwise. In the light of the deadly serious text, the fact that Sri Lanka walked blindly in diplomatic darkness with no cohesive strategy to lower or lessen the impact is deeply distressing. That too by telling Sri Lankans that the Government has rejected the UN Human Rights Commissioner Michele Bachelet’s report and the resultant Resolution. Click for the full text of the approved resolution co-sponsored by 41 countries.

In Geneva, however, Sri Lanka’s Permanent Representative C.A. Chandraprema, officially acknowledged the resolution and negotiated directly at the highest level over it, and what a hash it was. Now, Foreign Minister Dinesh Gunawardena told Parliament on Thursday that the resolution was illegal but did not seem to give reasons. Why negotiate on an illegal resolution? This is in marked contrast to Sri Lanka’s previous Foreign Ministers who did not take up such an untenable position.

In fact, during the negotiating process one of the core group members expressed surprise to the Foreign Ministry mandarins on the absence of Sri Lanka proposing alternate language to take care of concerns. This is when Chandraprema took part in informal consultations. Additionally, Sri Lanka could have done the same through proxy countries, that too by providing specific alternate language with a view to reducing the sting of the provisions. This is particularly with special reference to the Operative Paragraph 6 which dealt with developing further strategies for future accountability issues. Such a strategy has escaped the Sri Lankan side judging from the discussions at the informal consultations where the official transcript runs into more than 70 pages. To say there was no professional expertise on the Sri Lankan side, both in Geneva and in Colombo, is to mildly identify the reason. Little wonder a nation and its people were let down so badly by their own side.

Permanent Representative Chandraprema, in his final speech before the resolution was adopted, wound up with an interesting remark. He lamented that Sri Lanka’s request for changes had not been heeded and declared that therefore the country was rejecting the resolution. At first it was a case of official engagement. Then came the declaration of a rejection, which obviously is now the government policy. With that defiant stance, what would be the position of Sri Lanka be when the Human Rights Council meets for the 48th session in Geneva in September, where this issue is listed to be taken up as provided for by the resolution. How would Sri Lanka act in this instance? Can the Government discuss what FM Gunawardena said is “an illegal” subject? Would that not, if the argument is cogent, infringe on the country’s sovereignty and territorial integrity?

Twenty-two countries voted in favour – Argentina, Armenia, Austria, Bahamas, Brazil, Bulgaria, Cote d’Ivore, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Fiji, France, Germany, Italy, Malawi, Marshal Islands, Mexico, the Netherlands, Poland, Republic of Korea, Ukraine, the United Kingdom and Uruguay. This is the lowest vote against Sri Lanka since 2009 when 12 countries voted. Subsequently in 2012 there were 23 countries that voted against, 25 countries in 2013 and 23 countries in 2014. There was no voting in 2015, 2017 and 2019 when Sri Lanka co-sponsored a rollover by consensus.

On an overall basis, Tuesday’s outcome demonstrates the difficulty to consolidate geopolitically, to which the proponents of the Resolution should pay heed. Sri Lanka should seek to work with those countries that abstained in a bid to secure their full support, which may be needed in the future. For this, there is no gainsaying that persons with an extremely high degree of professionalism are required.

Here again, member countries do have foreign policy considerations. Take for example Venezuela, which is strongly opposed to western nations. As a matter of principle, Cuba does not support “country specific” resolutions, its delegate told the Council. Sri Lanka has consistently supported Cuba when being a member of the Human Rights Council and also in the UN General Assembly.

Here again, member countries do have foreign policy considerations. Take for example Venezuela, which is strongly opposed to western nations. As a matter of principle, Cuba does not support “country specific” resolutions, its delegate told the Council. Sri Lanka has consistently supported Cuba when being a member of the Human Rights Council and also in the UN General Assembly.

Ambassador Chandraprema worked a quid pro quo deal by voting in favour of the east African state of Eritrea on an adverse resolution against it over human rights violations. Eritrea in turn voted for Sri Lanka. During the separatist war in Sri Lanka, Eritrea was used by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) as a transhipment base to move military hardware to Sri Lanka. They even refused to host a Sri Lankan envoy in the country forcing the Foreign Ministry at that time to station Major General Amal Karunasekera, a former Director of Military Intelligence, at the Sri Lanka diplomatic mission in Cairo (Egypt) to overlook Eritrea.

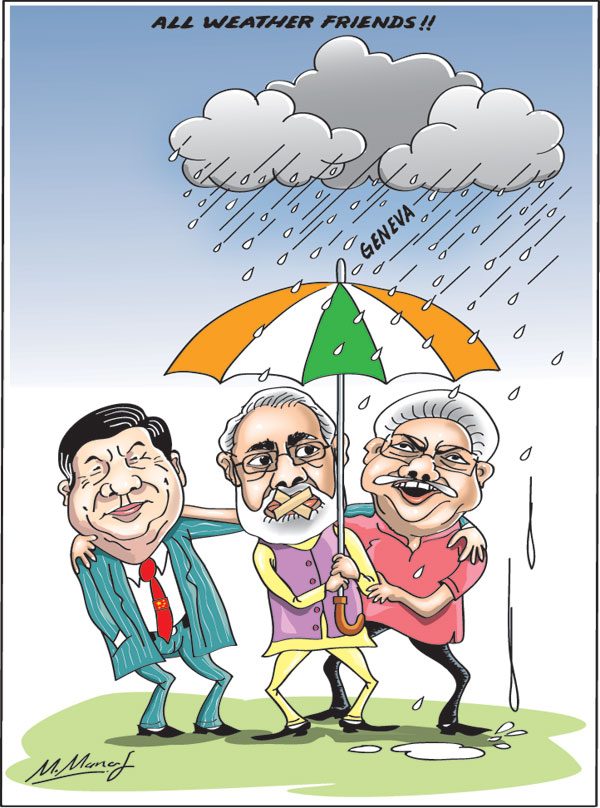

Foreign Secretary Colombage last week broke protocol to visit the Russian Embassy in Colombo to urge Russia to prevail upon Uzbekistan to support Sri Lanka. The episode is akin to the Peter Sellers comedy Pink Panther and reminds one of Inspector Jaques Clouseau. This fictional Inspector blunders but achieves his end. Yet, Uzbekistan was magnanimous and principled on its part, considering that Sri Lanka failed to vote in favour of it in the Human Rights Council. Bangladesh has withstood pressure from within the South Asian region and crowned Prime Minister, Mahinda Rajapaksa on his visit to Dhaka last week with its support. China, Pakistan, and the Russian Federation continued their traditional support for Sri Lanka. Bolivia also favoured Sri Lanka in the past.

The countries that abstained were Bahrain, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Gabon, India, Indonesia, Japan, Libya, Mauritania, Namibia, Nepal, Senegal, Sudan, and Togo. It is noteworthy that though Japan abstained, it constructively engaged in the informal consultations. This is notwithstanding the Government’s withdrawal of the Japanese-funded Light Rail Project and the East Container Terminal together with India.

The government’s first reaction came within hours of the resolution being adopted. Foreign Minister Dinesh Gunawardena declared at a hurriedly convened news conference that “This is an incredibly happy moment for us. The session is a victory for Sri Lanka. Only 22 countries out of 47 have voted in favour of the resolution. Those who had abstained were 14 countries.” That he argued meant that the votes for Sri Lanka and the abstentions were more. He said that the resolution “is not binding on Sri Lanka.” That brilliant theory in maths was first proclaimed by Professor and Minister G,L, Peris in 2014 when Sri Lanka lost a resolution. Here again, Gunawardena appears to be taking up the position that the issues arising from the resolution would end there. Would that also mean there would be no more dialogue with the Human Rights Council, particularly in view of the 48th UNHRC sessions in September?

Further, would such a standoff attitude on the part of Sri Lanka give rise to the core group to push the issue into the UN Security Council (UNSC) at a later stage? As is well known, the UNSC is the only body which can dish out decisions that are legally binding. Whilst veto power can be used on UNSC Resolutions, to foist a country on the agenda of that august body requires the support of eight countries. Being on the agenda of the UNSC has much negative ramifications. This also raises the issue of professional expertise to avoid the issues related instead of using amateurs with megaphone diplomacy.

In trying to suggest at his news conference that the total vote for Sri Lanka and the abstentions (11 + 14 = 25) outweigh the votes in favour of the resolution is a silly misnomer. Not even a three-wheeler scooter driver will believe in such a claim. Going by FM Gunawardena’s skewed logic, one could argue, tongue in cheek, that Sajth Premadasa won the November 2019 presidential elections and not Gotabaya Rajapaksa. In fact, Premadasa pointed this out after interrupting FM Gunawardena during his speech in Parliament. This is if all the votes the other opposition candidates received and those who were registered but did not cast their votes are added together. Of course, Gunawardena would not have been in a position then to say it was the happiest day for Sri Lanka.

Not even the Government’s political backers will believe in such a puerile argument. It is an insult to the intelligence to any citizen of this country. How this result could be termed a victory by Foreign Minister Gunawardena is misplaced, considering the far-reaching provisions of the Resolution. With regard to the vote numbers all that can be said is that the proponents were unable to clinch the real majority of 24. Sri Lanka’s illustrious Foreign Ministers like the late Lakshman Kadirgamar and even A.C.S. Hameed, if they were living, would have been ashamed at the pathetic conduct of the country’s external relations today. The sooner the alliance leaders realise this the better it is for them and the people of Sri Lanka.

Some of the other countries that abstained also had their own reasons to do so. Take for example Bahrain, a member of the Organisation of Islamic Countries, to which government leaders personally spoke, was showing its unhappiness over what its perceive as ill-treatment of Sri Lanka’s Muslim minority. So are Libya and Sudan. However, Pakistan and Bangladesh, which are also Muslim nations, voted for Sri Lanka. Pakistan made a firm commitment after the government heeded a request by its Prime Minister Imran Khan to allow burials of Muslim Covid-19 victims. The Government also halted a move to ban Burqa and Niqab and a clampdown on Madrasas or Muslim religious schools.

Ahead of Premier Mahinda Rajapaksa’s visit to Dhaka, Bangladesh agreed it would vote against the resolution. South Asian solidarity ended there when Nepal abstained. South Korea appears to have forgotten Sri Lanka’s support for its World Trade Organisation candidature. Fiji too appears to have forgotten Sri Lanka’s strong support when the Commonwealth considered punitive action against it after a coup in that country. It is also pertinent to note that Sri Lanka was once pressured to be one of six UN member countries to support a resolution against the UK. This was after its invasion of Falklands (Malvinas) in 1982 in what was widely seen as a flagrant violation of Argentina’s territorial integrity. The late President J.R. Jayewardene directed that the UK be supported. Such support was extended despite affirmation of double standards by the UK.

Why is Tuesday’s resolution much more serious than all previous ones? It is better explained in the words of Bob Last, Counsellor at the UK (the main sponsor) at his country’s Geneva mission. He presided over informal consultations that began on March 1. Giving an overview when the sessions began, he said there had been six resolutions “on promoting reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka. They date back to 2012.”

From 2012 to 2014, Last said, there were three successive annual resolutions. This culminated in the Human Rights Council establishing an international investigation in 2014, on alleged serious violations and abuses of human rights by the two sides to the conflict which ended in 2009. It was headed by Marzuki Darusman, a former Indonesian Attorney General. Following that investigation, the Council adopted by consensus the landmark 30/1 resolution which Sri Lanka itself co-sponsored.

The co-sponsorship was announced in Geneva by the then Foreign Minister, Mangala Samaraweera. It did come without the approval of the then President Maithripala Sirisena or the Cabinet of Ministers. One source said the then Prime Minister, Ranil Wickremesinghe, had given his consent to the move. Samaraweera may now be chuckling over the unsavoury developments that have come. Other than the approval aspects, while he could argue that he is now vindicated, one would wonder for how long the half-hearted action vis-à-vis the original resolution would have been acceptable to the proponents. Further, it is difficult to exonerate himself for in effect through co-sponsorship he had sold out the security forces who fought the separatist war.

If the sponsorship itself was a controversial move, withdrawal from it was much worse when looked at retrospectively. There was only a consensus vote in 2015, 2017 and 2019 – all during the previous yahapalana government.

In 2020, Foreign Minister Gunawardena, however, told the Human Rights Council that Sri Lanka was withdrawing from resolution 30/1. This was a turning point. That prompted the core group to take up the position that they would still remain “committed to the key principles underpinning resolution 30/1.” The Government rejected Human Rights Council moves to continue any further with this Resolution. Observers contend that if it were accepted, the debate would have centred largely on matters related to a hybrid court to hear alleged war crimes. There was some room to negotiate its composition and persuade the sponsors though one cannot say they would have ended positively. Sri Lankan judges who are now serving abroad could have been suggested, like it had been mooted by the previous government in line with the co-sponsorship. Like the co-sponsorship, the withdrawal also was more for political reasons with no study of the nuances in both cases.

This withdrawal led to the birth of the new and harder draft resolution, being adopted by the UNHRC last Tuesday. It did have the usual concerns of “accountability and political obstruction to prevent accountability for past crimes and human rights violations, militarisation of civilian functions, intimidation of media, civil society and marginalisation of Tamil and Muslim communities.” This Resolution has metamorphosised into an all-encompassing dictate. One can only hope the Government will put into place an accountability process on the abuses of the LTTE, as stressed in Operative Paragraph 4 of the Resolution. This would call in the proving of the bona fides of the supporters of the Resolution who are welcoming home the LTTE rump. Adele Balasingham’s residency in the UK is a case in point.

However, the resolution’s most explosive part is new and twofold: (1) to further strengthen the capacity of the Office of the UN Human Rights Commissioner to consolidate, analyse and preserve information and evidence. This goes hand in glove with the proposed International Court in 30/1. It is therefore evident that the end game of both these Resolutions is the same – the prosecution of persons, targeting specially the military and the political leadership at any cost. (2) to develop strategies for future accountability processes. As is clear, this is far more serious and deals with issues in the months and years to come. The trajectory ahead is clear. Government leaders have to take serious cognisance of them. Sections of the government believe their leaders have not taken the implications of the new resolution “quite seriously.”

In order to give effect to this part of the resolution, Goro Onojima, Secretary of the Human Rights Council, on Tuesday circulated among member countries of the Council the budget implications. They are to set up a 13-member Secretariat and require US$ 2,856,300 for the current year. The Secretariat will comprise investigators and lawyers, among others. Provision is also to be made for three years thereafter. The allocations from the regular budget are decided by the UN’s Fifth Committee.

Such a Secretariat will collect evidence for use by countries which exercise universal jurisdiction. In effect this may result in military personnel — who fought bravely in the separatist war against the LTTE, the world’s deadliest terrorist outfit — face the risk of being arrested when they are overseas and tried in foreign courts. The same threat would also apply to political and civil leadership linked to the separatist war. A far more damaging consequence would be the outcome of the Resolution acting as a deterrent to foreign investment. Therefore, the argument that the resolution is not binding on Sri Lanka is very hollow. Economically speaking, tariff benefits in the US market, the GSP plus benefits from the European Union too could face a threat depending on the Government’s delivery of the contents of the resolution. Already initial action on such measures has been fuelled by the Government’s “rejection” and Foreign Minister Gunawardena calling it “illegal.”

It is further exacerbated since this prescribed action seems to be the commitment of United States judging from a tweet from its Permanent Mission in Geneva. It said that “the Resolution adopted highlights continuing impunity for serious crimes and abuses and authorizes collection of evidence for future prosecutions,” which is in line with provisions of Operative Paragraph 6. The target for future prosecutions could be to a great extent military officers who conducted the separatist war as well as politicians and bureaucrats.

It is ironic if not tragic that experienced officials in the Foreign Ministry or those in the Permanent Mission in Geneva did not seek to mount a concerted campaign. They could easily have called for a separate vote on that clause last Tuesday. A clause-by-clause vote is allowed. This could have lessened the sting. There would have been member countries who would have empathised on this subject and supported it. Sadly, it was a stone left unturned due to the absence of a well-considered strategy and the acute lack of professionalism.

A significant feature of the voting at the Human Rights Council was India’s abstention – a fact which was projected in the Sunday Times (Political Commentary) of February 28. However, last week Foreign Secretary retired Admiral Professor Jayanath Colombage declared in Colombo that India would support Sri Lanka. This was merely based on an articulated position that India would not go against Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. It turned out to be what is diplomatically called a terminological inexactitude or simply untrue. It seemed a transparent ploy of seeking India’s support for Sri Lanka through media pressure.

That it embarrassed the Indian Government is one thing. The other is a bigger question of why statements which are not factual are often repeated on behalf of the Government and the country, something which no other Foreign Secretary had done in the past. Unfortunately, the Government’s credibility, both domestically and internationally, has taken a nosedive, in addition to calling into question the Foreign Secretary’s own integrity. That those gaffes have cost the country very dearly is no secret. Also laughable in this context is Foreign Minister Gunawardena’s claim of those who abstained had voted for Sri Lanka. Does this mean India too voted in favour?

Sri Lanka’s conduct of external relations has been so appalling that it had not been able to win back two friendly neighbours – India and Nepal. “The spectre of injustice comes to haunt the perpetrators of Sri Lankan (alleged) war crimes,” said the Kathmandu Post, a national newspaper in Nepal. India voted in favour of Sri Lanka in 2009, 2012 and 2013. In 2014, it abstained and during the next three years the voting was by consensus. Historically, Indian governments have always given primary consideration to local compulsions. In both 2012 and 2013, the then Congress government was in coalition with the Dravida Munnetra Kazhakam (DMK). The Tamil Nadu based party threatened to quit the coalition in New Delhi. That compelled India to vote for the resolution.

The haphazard way the proposed award of the Eastern Container Terminal (ECT) to India and Japan was cancelled shattered New Delhi’s confidence in Colombo. It was done despite a promise and with little or no warning. Another was the energy project in Delft Island being given to a Chinese company. Colombo’s explanation was that the award followed an Asian Development Bank (ADB) tender. Yet, there has been no intimation to New Delhi in advance thus creating apprehensions. This clearly shows that there has been no dialogue with Sri Lanka’s closest neighbour and, as pointed out many times the High Commissioner’s post has remained vacant for 15 months. This is with the closest neighbour of Sri Lanka.

South Indian political leaders reacted angrily to Colombage’s remarks. INDIA TODAY quoted DMK leader Muthuvel Karunanidhi Stalin, as saying he was shocked to hear the Sri Lankan Foreign Secretary’s statement that he expected India to stand by Sri Lanka ahead of the UNHRC meet on the island nation’s rights and accountability record. In Tamil Nadu, several political parties had urged the Centre to vote in favour of the resolution tabled at the UNHCR, saying that a Sri Lankan official had declared India would support Sri Lanka, said the Times of India. Added the HINDUSTAN TIMES: Indian Premier Narendra Modi’s silence “has caused shockwaves to Tamils around the world and in Tamil Nadu after Sri Lankan Foreign Secretary Jayanath Colombage had said that India would support his country.” Similar accounts appeared also in the Tamil media in Tamil Nadu.

These reports have embarrassed the officials in the External Affairs Ministry in New Delhi. It is no secret that Foreign Minister Gunawardena and Secretary Colombage are at variance on different issues. However, both seem to share a penchant for confusing the public through a numbers game. Minister Gunawardena is on record as saying 18 countries would support Sri Lanka whilst Secretary Colombage said 21 countries. They did not identify how many were Council members. One is not sure whether this was due to their own ignorance or simply playing out a strategy of keeping the Sri Lankan polity at bay. Of course, the international community would have seen through this approach of the Foreign Ministry’s leadership. Unless the Government ensures a high degree of professionalism in the Foreign Ministry and key diplomatic missions overseas there will be more damage caused. Besides there being no head of mission in New Delhi for 15 months, there are also no envoys in Ottawa (Canada), Riyadh (Saudi Arabia), Rome (Italy) and Canberra (Australia).

Apart from the demands contained in the Human Rights Council resolution, India had also unreservedly extended an open ultimatum to Sri Lanka, based on the implementation of the 13th Amendment to fulfil commitments on political devolution. A statement from the Indian government was read out ahead of the voting. It said: “India’s approach to the question of human rights in Sri Lanka is guided by two fundamental considerations. One is our support to the Tamils of Sri Lanka for equality, justice, dignity, and peace. The other is in ensuring the unity, stability, and territorial integrity of Sri Lanka. We have always believed that these two goals are mutually supportive and Sri Lanka’s progress is best assured by simultaneously addressing both objectives.

“India supports the call by the international community for the Government of Sri Lanka to fulfil its commitments on the devolution of political authority, including through the early holding of elections for provincial councils and to ensure that all provincial councils are able to operate effectively, in accordance with the 13th Amendment to the Sri Lankan Constitution.

“At the same time, we believe that the work of OHCHR should be in conformity with mandate given by the relevant resolution of the UN General Assembly.

“We would urge that the Government of Sri Lanka carry forward the process of reconciliation, address the aspirations of the Tamil community and continue to engage constructively with the international community to ensure that the fundamental freedoms and human rights of all its citizens are fully protected.”

That statement was read out by Third Secretary Pavan before the commencement of last Tuesday’s vote. Even that did not contain the country’s position on the vote. It is accepted diplomatic practice that in the event countries with whom a strong bi-lateral relationship is shared would seek to make known the voting position to the country concerned at least through a confidential discussion. They will make known the basis and their concerns for such action, especially if it is not possible to extend a supportive vote. In this instance, that was not to be. Was this an act to demonstrate Sri Lanka’s untrustworthiness following its questionable behavior? This could very well be.

India’s call to Sri Lanka to engage “constructively” with the international community in ensuring the human rights of “all” the citizens are “fully” protected. Such dictates seem to emanate from a displeased India. It is high time the Government had a hard inward look into the conduct of its foreign policy, which is abysmal at present. The need for specialised skills must be recognised. The need of the hour is well-trained career officials to be better engaged by the political authorities when formulating positions and in the conduct of foreign relations. If not, the entire country will be at sea in this sphere. Let not Sri Lanka’s external relations sink in the current turbulent international waters. There are able lifeguards in the foreign service.

It is important to note that the two main bodies which backed the resolution on Sri Lanka – the London based Global Tamil Forum (GTF) and the Tamil National Alliance (TNA) — had better coordinated strategy. In the past years, their representatives travelled to different world capitals to meet those in the corridors of power to garner support. This time, however, all that was done virtually via online. It also succeeded in obtaining support from the New York University to co-host a webinar to highlight the issues before the Human Rights Council. “We have no diplomats, High Commissioners or Ambassadors. We have no missions. Yet, we did what was needed to bring the issues affecting the Tamil people before the Human Rights Council,” said Suren Surendiran, spokesperson for the GTF. He added “the GTF and their affiliates in different countries stand united to achieve their goal in seeking justice.”

There are plenty of lessons to be learnt from the outcome of last Tuesday’s Human Rights Council adoption of the resolution on Sri Lanka. What is foremost and urgent is for the government to ensure that future issues are placed in the hands of experienced professionals instead of amateurs who have already done colossal damage. The “our man” syndrome that prevents such measures would only cause a diplomatic calamity. So will the advisory bodies that are pushing their own agenda be it for Covid-19, economy, or foreign policy on the wrong path. The writing is on the wall.

What the voting pattern showsGovernment ministers described last Tuesday’s resolution on Sri Lanka, adopted by the UN Human Rights Council, as the handiwork of the United States and western alliance against the Global South. However, the voting pattern clearly suggests otherwise. Here are some salient features:

| |

How it came tumbling down at the UNHRC in Geneva