Columns

- Canada and Saudi Arabia have not accepted Sri Lanka’s envoys; India says ‘no’ to Cabinet rank envoy

- UNHRC report before 45th sessions (obtained by the Sunday Times) calls for tough action including travel ban and assets freeze

- A new Commission of Inquiry to probe war-related matters

- New Delhi lodges strong protest over Palk Strait boat incident

Britain’s wartime Prime Minister, Sir Winston Churchill, said, “Diplomacy is the art of telling people to go to hell in such a way that they ask for directions.” American playwright, actor, and journalist Will Rogers declared, “Diplomacy is the art of saying ‘nice doggie’ until you can find a stone.” Added Adolf Hitler, “when diplomacy ends, war begins.”

At least in the conduct of Sri Lanka’s diplomacy, those definitions have become increasingly irrelevant. There have been envoys posted from Colombo to important capitals but they had served more the interests of the host and their own. There were political appointees who have been a colossal embarrassment. One of them, in a war-torn country, was cooking food in his hotel suite to save money. He ran short of green chillies and went to the hotel kitchen to beg for a few green pods.

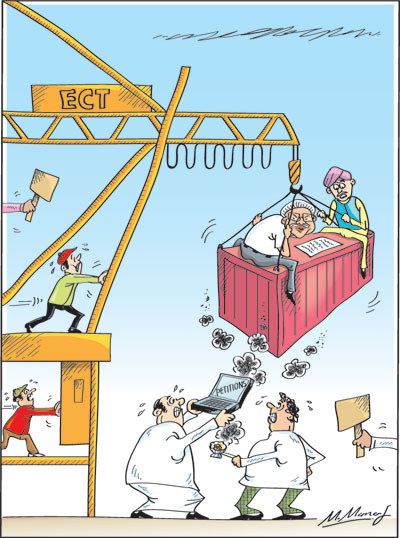

And now, questions have been raised about the selection process for Sri Lankan envoys. Two governments, Canada, and Saudi Arabia have not extended the agrément for Sri Lanka’s nominees to those countries. India, the third, has rejected a Sri Lankan request to offer ‘cabinet rank’ to our envoy. The agrément or an agreement by a state is to receive members of a diplomatic mission from a foreign country. The designated person enjoys immunity. A delay in such acceptance, in diplomatic practice demonstrates the reluctance of the host country to accept such a nominee. They are not expected to provide reasons for such action.

Among the three, the most important is neighbouring India. The envoy is Milinda Moragoda, a onetime Cabinet minister and prime mover of the Pathfinder Foundation, which receives funding from different sources including the United States and China. It also has shareholding in a hotel chain in the north. His nomination was approved by the High Posts Committee of Parliament on September 25, last year. In seeking his agrément, the Sunday Times learnt that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had also sought a ‘cabinet rank’ position, this being the first of this kind. The agrément has been accepted by New Delhi just last month.

However, this is not to be. Now, Moragoda has told government leaders that he is not interested in the posting thus leaving the position in New Delhi vacant. Government leaders are looking for new candidates now.

This may be the reason for Moragoda not being a member of the Sri Lankan side when Indian External Affairs Minister Dr Subramaniam Jaishankar visited Sri Lanka this month. In particular, he was not present when the visiting dignitary met President Gotabaya Rajapaksa or Foreign Minister Dinesh Gunawardena. In terms of protocol, the Sri Lankan Foreign Ministry did not consider him “High Commissioner-designate,” a highly placed source familiar with the developments said.

Yet, a top official in the Foreign Ministry directed the Protocol Division to somehow arrange a meeting for Moragoda with Jaishankar. According to the same source, “due to his hectic schedule, aides of the External Affairs Minister said he could afford a few minutes.” Moragoda handed over to Jaishankar a copy of Pathfinder Foundation’s report on Indian Ocean Security after a two-day event conducted by it. Photographs were taken. “Immediately thereafter, EAM Jaishanker left the Presidential Suite at Taj Samudra for his next appointment.

Yet, a top official in the Foreign Ministry directed the Protocol Division to somehow arrange a meeting for Moragoda with Jaishankar. According to the same source, “due to his hectic schedule, aides of the External Affairs Minister said he could afford a few minutes.” Moragoda handed over to Jaishankar a copy of Pathfinder Foundation’s report on Indian Ocean Security after a two-day event conducted by it. Photographs were taken. “Immediately thereafter, EAM Jaishanker left the Presidential Suite at Taj Samudra for his next appointment.

In preparing for the High Commissioner position in New Delhi, Moragoda had also made a key requirement — that he picks the Sri Lanka Deputy High Commissioners in Chennai and in Mumbai. He had in fact identified Vethody Kumaran Valsan for DHC in Chennai. Valsan served in that post earlier when Ranasinghe Premadasa was President. He also served a stint as Sri Lanka’s Ambassador in Sweden. They were still on the lookout then for a DHC in Mumbai. The position had earlier remained under the Commerce Department and is now brought under the purview of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Canada is delaying the agrément of former Air Force Commander, Air Chief Marshal Sumangala Dias. His appointment was cleared by Parliament’s High Posts Committee on November 9, last year. Quite clearly, in proposing his name as High Commissioner to Canada, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had lost sight of another reality. Canada is a member of the core group of the Geneva resolution on Sri Lanka and has called for security reforms among other matters. Additionally, the militancy of the Tamil diaspora in several Canadian capitals is all too well known. It should have thus been clear that it was not in the best interests of the motherland and the nominee himself. ACM Dias was the 17th Commander of the SLAF and retired on November 2, last year. As is clear, his appointment had been decided upon earlier and he faced the High Posts Committee in just a week.

It may be recalled that onetime Elections Commissioner Chandrananda de Silva served as Defence Secretary from December 7, 1993 to December 5, 2001. A highly respected state official, he was nominated as Sri Lanka’s High Commissioner to Canada. However, his agrément was left pending in silence. Though for no fault of his, the non-acceptance was an embarrassment. ACM Dias’ dilemma now is the prospect of being nominated to another country as envoy. The stigma of originally being rejected by one country before would be haunting personally and does not augur well for the country.

However, Ottawa accepted General Tissa Indika Weeratunga, onetime General Officer Commanding (GOC) the Joint Operations Headquarters (JOH) and Army Commander from 1981 to 1985. At that time Canada was not censuring such appointments from the military. The early part of his tenure saw protests from pro-Eelam groups but he completed his term. A highlight of that tenure was a visit by President Premadasa to Canada.

Saudi Arabia has still not accepted the nomination of Ahmed A. Jawad, a career foreign service officer who is due to retire in weeks, as Sri Lanka’s Ambassador. His appointment was cleared by the High Posts Committee of Parliament on November 9, last year.

Jawad has served previously in Saudi Arabia as Sri Lanka’s Ambassador. He then figured in a spat between Colombo and Riyadh over Rizana Nafeek, a housemaid who was beheaded on January 9, 2013 for killing a four-month-old child, Naif al Quthubai. Jawad was recalled to Colombo. In a retaliatory move, Saudi Arabia also recalled its Ambassador Abdulaziz bin Abdul-Rahman Al-Jammaz. Quite clearly, these facts have not been taken into consideration when the Foreign Ministry nominated Jawad for a second posting in Saudi Arabia.

UNHRC sessions

That these developments come at a time when Sri Lanka needs to maintain a close dialogue at the highest levels with New Delhi, Ottawa and Riyadh is imperative. Most important among them is New Delhi, particularly in the light of Sri Lanka featuring at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva. In this context, it is relevant to note that more than twenty top positions in President Joe Biden’s administration have gone to Indian-Americans. This is in respect of matters relating to democracy and human rights. The Government must not lose sight that the US spearheaded the resolutions in Geneva in the first instance. A review on Sri Lanka is scheduled for February 24, earlier than anticipated. The deadline for tabling new resolutions would be noon Thursday, March 18.

Relations between Colombo and New Delhi have reached a rough patch. India has called for the full implementation of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution and the conduct of Provincial Council elections. Added to that, an incident in the Palk Strait, the waters that divide Sri Lanka and India, has led to a strong protest that the Navy allegedly attacked Indian fishermen. The Navy in turn defended its action saying a speeding Indian fishing craft had caused damage to one of its patrol craft. In fact, the Navy released photographs and a news release to back up its claims. The bodies of three fishermen and a sailor who died in the incident have been recovered. It has turned out to be a sensitive issue in Tamil Nadu where election is due to the State Legislative Assembly. It will be held in May for 234 seats.

For India, the seriousness of the issue is underscored by the course of action it took. The External Affairs Ministry in the south bloc in New Delhi summoned Sri Lanka’s acting High Commissioner, Niluka Kadurugamauwa to deliver a demarche. High Commissioner Gopal Baglay also lodged a strong protest with Foreign Minister Dinesh Gunawardena. The Indian External Affairs Ministry said issues pertaining to fishermen should be handled “in a humanitarian manner.” It added that the “understandings between the two Governments in that regard must be strictly observed. Utmost efforts should be made to ensure that there is no recurrence.”

On Friday, the Government announced one of its countermeasures in the wake of the UNHRC sessions in Geneva. A gazette notification issued by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa said a three-member Commission of Inquiry has been appointed to “investigate and inquire” into the following matters:

(a) Find out whether preceding Commissions of Inquiry and Committees which have been appointed to investigate into human rights violations, have revealed any human rights violations, serious violations of the international humanitarian law and other such serious offences.

(b) Identify what are the findings of the said Commissions and Committees related to the serious violations of human rights, serious violations of international humanitarian laws and other such offences and whether recommendations have been made on how to deal with the said facts.

(c) Manner in which those recommendations have been implemented so far in terms of the existing law and what steps need to be taken to implement those recommendations further in line with the present Government policy.

(d) Overseeing of whether action is being taken according to (b) and (c) above.

The Commission is headed by Supreme Court Justice A.H.M.D. Nawaz. He has served previously in Sri Lanka delegations to the UNHRC sessions in Geneva. Chandra Fernando, a retired Inspector-General of Police, and Nimal Abeysiri, a retired District Secretary, are the other members. They have been asked to submit their final report in six months. This is the second Commission of Inquiry. The first was the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) after the Tiger guerrillas were militarily defeated.

The origins of issues before the UNHRC resolutions against Sri Lanka came during the yahapalana (good governance) Sirisena-Wickremesinghe government. At that time, the then opposition defended its role when it was in governance. It took up the position that there was no violation of human rights or international humanitarian laws. The then President Mahinda Rajapaksa forcefully defended the troops. He declared, at the end of the separatist war, that they fought with a gun in one hand and the UN Human Rights Charter on the other.

The Commission of Inquiry announced by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa signals a marked shift. Though somewhat belated, the first task is to ascertain whether there have been any findings of serious violations of human rights or international humanitarian laws. The idea of the government is to adopt “what steps need to be taken to implement those recommendations further in line with the present Government policy” in “terms of existing laws.” Though late, this is a step forward after Foreign Minister Gunawardena told the UNHRC last year about this probe. This was after a declaration that Sri Lanka would move away from the co-sponsorship of the US-backed resolution. He said the government would “pursue an “inclusive, domestically designed and executed reconciliation and accountability process.”

The critical question is whether the latest move by the Government would be acceptable to stakeholders of the issue, the 47 member states of the UNHRC or the western nations. One western diplomat, who did not wish to be identified, said, “It is too little too late. They are now trying to start from ground zero and seems a transparent ploy after so much of water has passed under the bridge.” However, Foreign Minister Gunawardena told the Sunday Times that several other steps were also being taken but declined to elaborate. He also refused comment when asked about diplomatic postings saying, “those are internal matters.”

The Sunday Times learnt that one such step is an immediate review of outlawed Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) suspects who have remained in custody for longer periods, some up to ten years. Whilst some of them are facing legal action, most are not. The Attorney General’s Department has been called upon to study these cases and make recommendations. Here again, one is not wrong in saying that this “thawing” is belated though it signals a shift. Quite apart from other issues, some 10,000 or more in jail being released, if there were no charges, would have freed up space in the prisons in the light of the fast-spreading and uncontrollable COVID-19 pandemic.

UN Human Rights High Commissioner’s report

The naming of a three-member Commission of Inquiry coincided with the release of the Report on Sri Lanka by United Nations Human Rights High Commissioner Michelle Bachelet, next week. The report is for the forty-sixth session of the UNHRC from February 22 to March 19, 2021. The draft of the report was sent to the Foreign Affairs Ministry in Colombo on November 22 last year and received written inputs to the contents on December 28, last year. On virtual format Foreign Ministry officials also discussed it with UNHRC officials in Geneva on January 7.

The 17-page report says the Government did not issue a visa for deployment of an additional international human rights officer as endorsed by the UN General Assembly pursuant to resolution 40/1. It adds that no Special Procedure mandate holders have visited Sri Lanka since August 2019.

It traces the history of the conflict and calls for an end to “military involvement in civilian activities, accountability for military personnel, and security sector reforms. Yet, the past year has seen a deepening and accelerating militarisation of civilian government functions – which the High Commissioner first reported to the Human Rights Council in February 2020 – particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Commenting on the COVID-19 pandemic, the report observes that it “has also impacted on religious freedom and exacerbated the prevailing marginalisation and discrimination suffered by the Muslim community.” It adds, “The High Commissioner is concerned that the Government’s decision to mandate cremations for all those affected by COVID-19 has prevented Muslims from practising their own burial religious rights and has disproportionately affected religious minorities and exacerbated distress and tensions. Although the Government asserted to OHCHR that this policy is driven by public health concerns and scientific advice, the High Commissioner notes that WHO guidance stresses that “cremation is a cultural choice.” Sri Lankan Muslims have also been stigmatised in popular discourse as carriers of COVID-19 — a concern raised by the High Commissioner in her global update to the Council in June 2020.”

In this backdrop, the US Ambassador in Sri Lanka, Allaina B. Teplitz, tweeted on Friday that “Ratified by Sri Lanka in 1955, UDHR (Universal Declaration of Human Rights) article 18 states that everyone has the right to manifest their religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance. Covid created global challenges, but it should not cost us our compassion and respect for one another’s belief. We stand with all families; who’ve lost loved ones to this pandemic. Their right and dignity should be respected by permitting the observance of the faith in accordance with international public health guidelines.” That the message came just ahead of the release of the UN High Commissioner’s report on Sri Lanka is noteworthy.

The report’s recommendations and conclusions are significant and far reaching. A Foreign Ministry official said Sri Lanka’s own response to the report would be made known at the UNHRC sessions. Here is what the report, a copy of which was obtained by the Sunday Times, says:

“Nearly 12 years on from the end of the war, domestic initiatives for accountability and reconciliation have repeatedly failed to produce results, more deeply entrenching impunity, and exacerbating victims’ distrust in the system. Sri Lanka remains in a state of denial about the past, with truth-seeking efforts aborted and the highest State officials refusing to make any acknowledgement of past crimes. This has direct impact on the present and the future. The failure to implement any vetting or comprehensive reforms in the security sector means that the State apparatus and some of its members credibly implicated in the alleged grave crimes and human rights violations remain in place. The 2015 reforms that offered more checks and balances on executive power have been rolled back, eroding the independence of the judiciary and other key institutions further.

“The beginnings of a more inclusive national discourse that promised greater recognition and respect of and reconciliation with minority communities have been reversed. Far from achieving the “guarantees of non-recurrence” promised by resolution 30/1, Sri Lanka’s current trajectory sets the scene for the recurrence of the policies and practices that gave rise to grave human rights violations. While fully appreciating the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the High Commissioner is deeply concerned by the trends emerging over the past year, which represent clear early warning signs of a deteriorating human rights situation and a significantly heightened risk of future violations, and therefore calls for strong preventive action. Despite the Government’s stated commitment to the 2030 Agenda, Tamil and Muslim minorities are being increasingly marginalised and excluded from the national vision and Government policy, while divisive and discriminatory rhetoric from the highest State officials risks generating further polariaation and violence.

“The High Commissioner is concerned that the emergency security deployments that followed the Easter Sunday terrorist attacks in 2019 have evolved into an increased militarisation of the State. The Government has appointed active and former military personnel, including those credibly implicated in war crimes to key positions in the civilian administration, and created parallel task forces and commissions that encroach on civilian functions. Combined with the reversal of important institutional checks and balances on the executive by the 20th Constitutional Amendment, this trend threatens democratic gains.

“The High Commissioner is alarmed that the space for civil society, including independent media, which had widened in recent years, is rapidly shrinking. The High Commissioner urges the authorities to immediately end all forms of surveillance, including intimidating visits by State agents and harassment against human rights defenders, lawyers, journalists, social actors and victims of human rights violations and their families, and to refrain from imposing further restrictive legal measures on legitimate civil society activity.

“The Human Rights Council therefore is – once again – at a critical turning point in its engagement with Sri Lanka. Twice before, the Council has leant its support to domestic accountability and reconciliation initiatives, culminating in resolution 30/1. The Government has now demonstrated its inability and unwillingness to pursue a meaningful path towards accountability for international crimes and serious human rights violations, and signalled instead a fundamentally different approach which focusses on reparation and development but threatens to deny victims their rights to truth and justice and further entrench impunity.

“It is vital that the Human Rights Council takes further action on Sri Lanka for three important reasons. Firstly, the failure to deal with the past continues to have devastating effects on tens of thousands of survivors — spouses, parents, children, and other relatives — from all communities who continue to search for the truth about the fate of their loved ones, to seek justice and are in urgent need of reparations. Secondly, the failure to advance accountability and reconciliation undermines the prospects for sustainable peace, human and economic development in line with the 2030 Agenda and carries the seeds of repeated patterns of human rights violations and potential conflict in the future.

“Finally, the trends highlighted in this report represent yet again an important challenge for the United Nations, including the Human Rights Council, in terms of its prevention function. Independent review of the United Nations’ actions in 2009 in Sri Lanka concluded there had been a systemic failure of the prevention agenda as the conflict concluded. The international community must not repeat those mistakes, nor allow a precedent that would undermine its efforts to prevent and achieve accountability for grave violations in other contexts.

“The High Commissioner welcomes the Government’s stated commitment to the 2030 Agenda and to continue some measures of peacebuilding, reparation and restitution, but Sri Lanka will only achieve sustainable development and peace if it ensures civic space and effectively addresses the institutionalised and systemic issue of impunity. However, by withdrawing its support for resolution 30/1 and related measures, and by repeatedly failing to undertake meaningful action across the full scope of that resolution, the Government has largely closed the possibility of genuine progress being made to end impunity through a domestic transitional justice process.

“In view of recent trends, the High Commissioner calls on the Human Rights Council to enhance its monitoring of the human rights situation in Sri Lanka, including progress in the Government’s new initiatives, and to set out a coherent and effective plan to advance accountability options at the international level.

“Member states have a number of options to advance criminal accountability and provide measures of redress for victims. In addition to taking steps towards the referral of the situation in Sri Lanka to the International Criminal Court, Member States can actively pursue investigation and prosecution of international crimes committed by all parties in Sri Lanka before their own national courts, including under the principles of extraterritorial or universal jurisdiction. The High Commissioner encourages Member States to work with OHCHR, victims and their representatives to promote such avenues for accountability, including through opening investigations into possible international crimes, and to support a dedicated capacity to advance these efforts.

“Member States can also apply targeted sanctions, such as asset freezes and travel ban against State officials and other actors credibly alleged to have committed or be responsible for grave human rights violations or abuses, as well as support initiatives that provide practical benefits to victims and their families.

Recommendations

The High Commissioner recommends that the Government of Sri Lanka:

- Actively promote an inclusive, pluralistic vision for Sri Lanka, based on non-discrimination and protection of human rights for all, and in line with the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda;

- Ensure constitutional and legislative reforms address recommendations made by United Nations human rights mechanisms and the resolutions of the Human Rights Council;

- Publicly issue unequivocal instructions to all branches of the military, intelligence and police forces that torture, sexual violence and other human rights violations are prohibited and will be systematically investigated and punished;

- Order all security agencies to immediately end all forms of surveillance and harassment of and reprisals against human rights defenders, social actors, and victims of human rights violations;

- Promptly, thoroughly, and impartially investigate and prosecute all allegations of gross human rights violations and serious violations of international humanitarian law, including torture and ill-treatment, and give the highest priority to ensuring accountability in long-standing emblematic cases;

- Remove from office security personnel and other public officials credibly implicated in human rights violations, in compliance with human rights standards; implement other reforms of the security sector to strengthen and ensure accountability and civilian oversight;

- Ensure structural safeguards for the Human Rights Commission to function independently and receive adequate resources;

- Ensure an environment in which the Office on Missing Persons and Office for Reparations can operate effectively and independently; provide both Offices with sufficient resources and technical means to effectively fulfil their mandate; and proceed with interim relief measures for affected vulnerable families with a gender focus, notwithstanding their right to effective and comprehensive reparations and rights to truth and justice;

- Establish a moratorium on the use of the Prevention of Terrorism Act for new arrests until it is replaced by legislation that adheres to international best practices;

- Establish standard procedures for the granting of pardons or other forms of clemency by the President, including subjecting it to judicial review, and excluding grave human rights and international humanitarian law violations;

- Honour its standing invitation to Special Procedures by scheduling renewed country visits by relevant thematic mandate holders; continue engagement with treaty bodies; and seek continued technical assistance from OHCHR in implementing the recommendations of UN human rights mechanisms. The High Commissioner recommends that the Human Rights Council and Member States to:

- Request OHCHR to enhance its monitoring of the human rights situation in Sri Lanka, including progress towards accountability and reconciliation, and report regularly to the Human Rights Council;

- Support a dedicated capacity to collect and preserve evidence for future accountability processes, to advocate for victims and survivors, and to support relevant judicial proceedings in Member States with competent jurisdiction.

- Cooperate with victims and their representatives to investigate and prosecute international crimes committed by all parties in Sri Lanka through judicial proceedings in domestic jurisdictions, including under the principles of extraterritorial or universal jurisdiction.

- Explore possible targeted sanctions such as asset freezes and travel bans against credibly alleged perpetrators of grave human rights violations and abuses;

- Apply stringent vetting procedures to Sri Lankan police and military personnel identified for military exchanges and training programmes;

- Prioritise support to civil society initiatives and efforts for reparation and victims’ assistance and prioritise victims and their families for assistance in their bilateral humanitarian, development, and scholarship programmes;

- Review asylum measures with respect to Sri Lankan nationals to protect those facing reprisals and avoid any refoulement in cases that present real risk of torture or other serious human rights violations.

- The High Commissioner recommends that United Nations entities:

- Ensure that the Secretary-General’s Call to Action on human rights guides all United Nations policy and programmatic engagement in Sri Lanka;

- Ensure that all development programmes are founded on principles of inclusion, non-discrimination, and support for effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions, in line with the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda;

- Incorporate strict human rights due diligence in engagement with the security forces and all bodies under the purview of the Ministry of Defence or the Ministry Public Security;

- Whilst fully understanding force generation challenges in the context of UN peacekeeping, keep under review Sri Lanka’s contributions to UN peacekeeping operations and screening systems for Sri Lanka personnel.

The recommendations contained in the Report are far reaching, and the trajectory of the envisaged action internationally has been outlined, which is invariant with that of the Government of Sri Lanka. There is a shrill call for the UNHRC to take further action on Sri Lanka by setting out an effective plan at the international level to pursue ‘a meaningful path towards accountability for international crimes and serious human rights violations,’ which the country has failed to do so at present.

In this context, initiatives outlined include the referral of human rights situation to the International Criminal Court (ICC). This broadly hints on the susceptibility of the issue being pushed towards the UN Security Council in New York, an aspect recently requested by the Tamil political parties and civil society groups. It further prescribes the member states to pursue investigation and prosecution in their national courts based on the principle of Universal Jurisdiction, on crimes committed by all parties. Travel bans, asset freezing, targeted sanctions as other suggested punitive measures need to be taken very seriously.

It is interesting to note that the outlined penal measures are against state officials and “other actors” which seems to be a recognition of the need to act on the LTTE. It is also pertinent to note that while the LTTE remains banned in 32 countries, its rump’s activities continue unabated in those soils.

The continued chorus in the Report that credible allegations of serious violations of international humanitarian law amounting to war crimes having been committed during the separatist war, however, remains unsubstantiated with the absence of substantive related evidence. However, the GoSL will need to work with interested parties in bringing about closure on this issue, which would need careful and extensive negotiations, considering it being politically charged internationally.

Conundrum over diplomatic postings